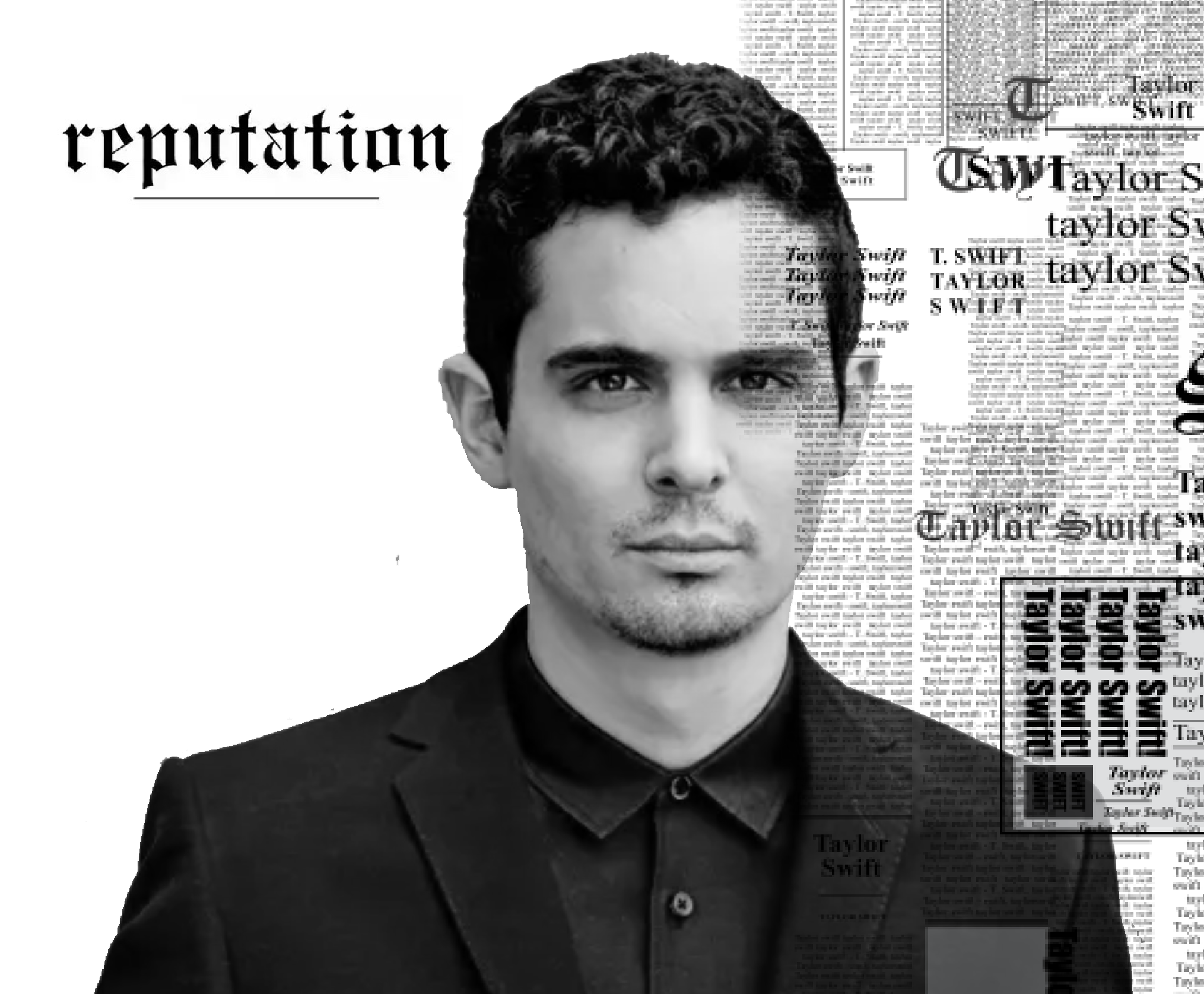

Damien Chazelle Is in His Reputation Era

“Oh, I'm sorry, the old Damien can't come to the phone right now. Why? Oh, 'cause he's dead."

By Brooke metayer

02.08.2023

In August of 2017, Taylor Swift emerged from a hiatus with the announcement of an album like nothing we had seen from her before: reputation. A complete rebrand. She slipped us an exposed shoulder and wet, slicked-back hair in a black-and-white photo to show us she was a “bad girl” now, ready to call out the people and systems in the industry that drove her to rebel.

In the years since, the widely approved term “reputation era” emerges from time to time: washing over the comment sections underneath Getty photos of recently single celebrities wearing dark lipstick at red carpet events, taking shape in the slurred words of drunk girls snorting expensive drugs in clean bathrooms, standing in as a cutesy synonym for ditching the good-girl image in favor of something more “real” and “gritty.” But the “reputation era” is not simply high heels and blocking your ex on Instagram—it is these things, but done with a true Taylor Swift spirit, which is far less effective and far more desperate.

I last uttered the phrase about a week ago to my friend Hannah after an opening-night screening of Babylon, the latest film directed by Academy Award-winning filmmaker Damien Chazelle.

“He is SO in his ‘reputation era,’” I said of Chazelle, swinging the heavy door open and rolling my eyes.

And I meant it. Something about the wild yet precisely curated chaos reminded me of the Taylor from 2017, the one who talked about getting drunk more than any other 27-year-old I’ve heard before and cursed with the diction of a child trying to impress a friend’s older sibling. Because behind the mounds of coke, topless women, and general debauchery on screen in Babylon, I saw a Harvard nerd who just wants to be taken seriously and acknowledged amongst the ranks of the perverted geniuses who came before him.

Some may call me crazy, or probably bored, but I believe I have the grounds to make an argument that no one asked for and say:

Damien Chazelle is the Taylor Swift of movies, and Babylon is his reputation—his own toothless rebellion against the systems that have done nothing but reward him.

Babylon is an epic of a film, spanning over three hours as it unravels the rise and fall of an ensemble of stars in various stages of fame and success. Their raw talents and destructive behaviors cynically cause their lives to fall apart, and fall apart, and fall apart even more, until there is nothing but blood and newspaper eulogies. Hollywood’s descent into hell is metaphorized heavy-handedly at around the two-hour mark, when Toby McGuire’s pale, rotting-toothed drug lord appears to lead us through sex dungeons, torture chambers, alligator swamps, and rat-eating muscle men. Our beloved characters are taken to new lows deep within the city where no one can save them.

Watching this, it is difficult to believe that just a few years ago, we watched La La Land’s Mia and Sebastian float into the stars above that same city, trusting those twinkling lights below to catch them if they fell.

La La Land, Chazelle’s 2016 film, is the antithesis of Babylon. As a musical comedy-drama with a dreamy color palette, it breathed new life into a bygone genre with thrillingly assured direction and an irresistibly sincere excess of heart. High necklines and tongueless kissing earned it a PG-13 rating, and characters broke out into energized musical numbers, literally tap-dancing in the streets.

Awe-inspired, warm, contained, and inoffensive, it absolutely swept that awards season, going on to win six Oscars, including Best Director. It was exactly the kind of film to romance voters in the industry and remind them that the pursuit of art is worth the trials and heartbreak. With its playful melodies and whimsical themes, dreams come true in La La Land.

Before reputation, there was 1989. 1989 is a straightforward pop album with a capital “P.” Leaning into more of the catchy melodies Swift experimented with on Red, the album is squeaky clean, concise, and expertly crafted. It is self-aware in its expression of pain but never goes so far as to deconstruct that pain further than a level that is still relatable to a broad audience. One of the most successful singles off the album is a self-confidence anthem titled “Shake It Off,” which is inclusive and inoffensive enough to be used for everything from Diet Coke commercials to youth cheerleading camp choreography. The album absolutely swept that awards season.

Before the Babylon title card even appears on screen, audiences are instantly aware that this is a different kind of Hollywood than La La Land’s. One with piss kinks, elephant shit, mounds of cocaine, and projectile vomit. This opening scene has the sick giddiness of a teenage boy discovering porn for the first time and the “you can’t tell me what to do” attitude to match. It’s an attitude reminiscent of reputation lyrics like, “If a man talks shit then I owe him nothing, don’t regret it one bit ‘cause he had it coming.”

But why does Damien have such a bone to pick with Hollywood all of a sudden? There are probably many reasons, from creating in a post-Weinstein Hollywood to the simple nuances of human emotion. There is no scientific reason the Babylon Hollywood and the La La Land Hollywood can’t exist simultaneously in the mind of one man. However, like most modern women, I get a sick enjoyment out of celebrity drama. Particularly, awards show drama.

In 2009, at the annual Video Music Awards broadcasted live on MTV, Taylor took the stage in a Cinderella gown to accept her VMA for her “You Belong With Me” music video. “Thank you so much!” she said. “I always dreamed about what it would be like to maybe win one of these someday, but I never thought it actually would have happened. I sing country music. So thank you so much for giving me the chance to win a VMA Award! I—”

That’s when Kanye sprang up and rushed the stage, taking the microphone out of Swift’s hand, effectively hijacking her big moment to give a shout out to Beyoncé for her nominated “Single Ladies” music video. The culture was nearly unanimously on Swift’s side. She was the underdog in this dynamic and people stood behind her in droves. Beyoncé herself even dedicated her acceptance speech later in the night for a different award to giving Swift a re-do.

But in 2016, midnight struck and Cinderella was allegedly exposed for the attention-seeking liar she really was when Kim Kardashian posted a video that revoked Swift’s victim card once and for all.

In the video, Swift’s voice echoes through a cell phone on a table next to Kanye it appears as though Swift had consented to West referencing her in his song “Famous”: a song she had been publicly criticizing him for as he names her in its lyrics without her consent. Snake emojis flooded Swift’s comment sections and #KimExposedTaylorParty trended on Twitter. She became too big to be the underdog in their dynamic, and Kardashian, the then-wife of West, proved she would play the victim like this any chance she got. (It was later revealed that this recording was edited and misleading; Swift did not agree to be referenced in the specific context in question.)

That year, unable to win back public opinion, even after a written Instagram statement, Swift went dark, taking to the shadows and writing her revenge manifesto. reputation was dripping with the bitterness of someone who had been misunderstood and misrepresented in the media. Nearly every song, even the soft love ballads like “Delicate” and “King of My Heart,” contain some kind of lyrical nod to her haters, doubters, and bad reputation.

Such a brief awards show moment snowballed over the years into something bigger, something worthy of fueling a rebellious passion project. I have to wonder how much of the 2017 Academy Awards Best Picture mishap led Chazelle to inject so much cynicism into Babylon—a film he himself refers to as a “hate letter to Hollywood.”

In case you haven’t heard: in 2017, at the 89th Academy Awards, presenters Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway were given a copy of the winner announcement card for Best Actress, which Emma Stone had just won for La La Land, instead of the card they were supposed to read. The one for Best Picture. A slightly confused Dunaway read the card, and not knowing exactly how to proceed, announced La La Land at the end of the ABC broadcast. The film’s team bounced to the stage to accept the award and the crowd applauded. Only after three acceptance speeches by the producers of the movie, a haphazard contingent consisting of stagehands and host Jimmy Kimmel stumbled onstage to correct the record: Moonlight had actually won Best Picture.

The more “real” and “gritty” Moonlight’s win over the escapist fairytale La La Land seemed to be indicative of a cultural shift, one quite serendipitously underlined by such a dramatic broadcasted moment.

In the sociopolitical climate of 2017 America, in the carnage of a tumultuous presidential race, a retro-romance film felt to voters to be in bad taste. Despite 14 nominations and six category wins, it seemed at that moment that a film would have to represent something larger culturally and politically in order to be Best Picture winner-worthy.

Given how much having the spotlight taken away from her at the 2009 VMAs influenced Swift's rebellion passion project, and given Swift and Chazelle have so many of the same artistic instincts, it is difficult to completely rule this theory out. If anything, it’s a juicy villain origin story.

The thing that makes Swift and Chazelle so cringey and easy to make fun of in this regard is the same thing that makes them such brilliant artists: their earnest commitment to what is emotionally true. They feel deeply and put force behind each frame, word, and breath in a way that builds into a cohesive, living, breathing work of art.

Babylon is expertly paced and emotionally thrilling; each camera movement and background extra is connected to the overall story. It is clear that the team behind it—the producers, casting directors, set designers, makeup artists, and so on—understood the vision of the project, taking the time to ensure that every square inch of the screen and every millisecond of expression had weight. The production is so grand yet somehow feels so simple. For the first hour and a half, I truly believed I was watching the best film ever made.

Swift’s talent lies in her ability to poetically articulate experiences with remarkable specificity, putting things humans often feel but don’t recognize into melodies. She does this through the process of trying to understand her own spread of emotions, figuring that if she is feeling them, there’s a chance many others have too. At this point, the mega-star’s daily life is vastly different from the average Swfitie’s, which results in a few less-relatable and very specific songs like “Look What You Made Me Do.” However, if she wasn’t writing about her deeply personal experiences, even the ones about how hard it is to be famous, she wouldn’t really be Taylor Swift.

On this Kanye West- and internet hater-focused album, we still get moments of clarity like, “Please don’t ever become a stranger whose laugh I would recognize anywhere.” These moments convey the menial yet consuming anxieties of life, such as navigating the early stages of a relationship or the impermanence of connection. Somehow, simple lyrics like this one help me understand my own fears and monotonous thoughts, making them tangible.

Maybe Swift and Chazelle are a bit bitter and come off a bit desperate, but it is refreshing to witness someone confident in their own truth. From this perspective, Babylon and reputation are not so much ruthless takedowns of industries as they are simply sincere and dorky little passion projects by exceptional artists.

In the years since, the widely approved term “reputation era” emerges from time to time: washing over the comment sections underneath Getty photos of recently single celebrities wearing dark lipstick at red carpet events, taking shape in the slurred words of drunk girls snorting expensive drugs in clean bathrooms, standing in as a cutesy synonym for ditching the good-girl image in favor of something more “real” and “gritty.” But the “reputation era” is not simply high heels and blocking your ex on Instagram—it is these things, but done with a true Taylor Swift spirit, which is far less effective and far more desperate.

I last uttered the phrase about a week ago to my friend Hannah after an opening-night screening of Babylon, the latest film directed by Academy Award-winning filmmaker Damien Chazelle.

“He is SO in his ‘reputation era,’” I said of Chazelle, swinging the heavy door open and rolling my eyes.

And I meant it. Something about the wild yet precisely curated chaos reminded me of the Taylor from 2017, the one who talked about getting drunk more than any other 27-year-old I’ve heard before and cursed with the diction of a child trying to impress a friend’s older sibling. Because behind the mounds of coke, topless women, and general debauchery on screen in Babylon, I saw a Harvard nerd who just wants to be taken seriously and acknowledged amongst the ranks of the perverted geniuses who came before him.

Some may call me crazy, or probably bored, but I believe I have the grounds to make an argument that no one asked for and say:

Damien Chazelle is the Taylor Swift of movies, and Babylon is his reputation—his own toothless rebellion against the systems that have done nothing but reward him.

Babylon is an epic of a film, spanning over three hours as it unravels the rise and fall of an ensemble of stars in various stages of fame and success. Their raw talents and destructive behaviors cynically cause their lives to fall apart, and fall apart, and fall apart even more, until there is nothing but blood and newspaper eulogies. Hollywood’s descent into hell is metaphorized heavy-handedly at around the two-hour mark, when Toby McGuire’s pale, rotting-toothed drug lord appears to lead us through sex dungeons, torture chambers, alligator swamps, and rat-eating muscle men. Our beloved characters are taken to new lows deep within the city where no one can save them.

Watching this, it is difficult to believe that just a few years ago, we watched La La Land’s Mia and Sebastian float into the stars above that same city, trusting those twinkling lights below to catch them if they fell.

La La Land, Chazelle’s 2016 film, is the antithesis of Babylon. As a musical comedy-drama with a dreamy color palette, it breathed new life into a bygone genre with thrillingly assured direction and an irresistibly sincere excess of heart. High necklines and tongueless kissing earned it a PG-13 rating, and characters broke out into energized musical numbers, literally tap-dancing in the streets.

Awe-inspired, warm, contained, and inoffensive, it absolutely swept that awards season, going on to win six Oscars, including Best Director. It was exactly the kind of film to romance voters in the industry and remind them that the pursuit of art is worth the trials and heartbreak. With its playful melodies and whimsical themes, dreams come true in La La Land.

Before reputation, there was 1989. 1989 is a straightforward pop album with a capital “P.” Leaning into more of the catchy melodies Swift experimented with on Red, the album is squeaky clean, concise, and expertly crafted. It is self-aware in its expression of pain but never goes so far as to deconstruct that pain further than a level that is still relatable to a broad audience. One of the most successful singles off the album is a self-confidence anthem titled “Shake It Off,” which is inclusive and inoffensive enough to be used for everything from Diet Coke commercials to youth cheerleading camp choreography. The album absolutely swept that awards season.

Before the Babylon title card even appears on screen, audiences are instantly aware that this is a different kind of Hollywood than La La Land’s. One with piss kinks, elephant shit, mounds of cocaine, and projectile vomit. This opening scene has the sick giddiness of a teenage boy discovering porn for the first time and the “you can’t tell me what to do” attitude to match. It’s an attitude reminiscent of reputation lyrics like, “If a man talks shit then I owe him nothing, don’t regret it one bit ‘cause he had it coming.”

But why does Damien have such a bone to pick with Hollywood all of a sudden? There are probably many reasons, from creating in a post-Weinstein Hollywood to the simple nuances of human emotion. There is no scientific reason the Babylon Hollywood and the La La Land Hollywood can’t exist simultaneously in the mind of one man. However, like most modern women, I get a sick enjoyment out of celebrity drama. Particularly, awards show drama.

In 2009, at the annual Video Music Awards broadcasted live on MTV, Taylor took the stage in a Cinderella gown to accept her VMA for her “You Belong With Me” music video. “Thank you so much!” she said. “I always dreamed about what it would be like to maybe win one of these someday, but I never thought it actually would have happened. I sing country music. So thank you so much for giving me the chance to win a VMA Award! I—”

That’s when Kanye sprang up and rushed the stage, taking the microphone out of Swift’s hand, effectively hijacking her big moment to give a shout out to Beyoncé for her nominated “Single Ladies” music video. The culture was nearly unanimously on Swift’s side. She was the underdog in this dynamic and people stood behind her in droves. Beyoncé herself even dedicated her acceptance speech later in the night for a different award to giving Swift a re-do.

But in 2016, midnight struck and Cinderella was allegedly exposed for the attention-seeking liar she really was when Kim Kardashian posted a video that revoked Swift’s victim card once and for all.

In the video, Swift’s voice echoes through a cell phone on a table next to Kanye it appears as though Swift had consented to West referencing her in his song “Famous”: a song she had been publicly criticizing him for as he names her in its lyrics without her consent. Snake emojis flooded Swift’s comment sections and #KimExposedTaylorParty trended on Twitter. She became too big to be the underdog in their dynamic, and Kardashian, the then-wife of West, proved she would play the victim like this any chance she got. (It was later revealed that this recording was edited and misleading; Swift did not agree to be referenced in the specific context in question.)

That year, unable to win back public opinion, even after a written Instagram statement, Swift went dark, taking to the shadows and writing her revenge manifesto. reputation was dripping with the bitterness of someone who had been misunderstood and misrepresented in the media. Nearly every song, even the soft love ballads like “Delicate” and “King of My Heart,” contain some kind of lyrical nod to her haters, doubters, and bad reputation.

Such a brief awards show moment snowballed over the years into something bigger, something worthy of fueling a rebellious passion project. I have to wonder how much of the 2017 Academy Awards Best Picture mishap led Chazelle to inject so much cynicism into Babylon—a film he himself refers to as a “hate letter to Hollywood.”

In case you haven’t heard: in 2017, at the 89th Academy Awards, presenters Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway were given a copy of the winner announcement card for Best Actress, which Emma Stone had just won for La La Land, instead of the card they were supposed to read. The one for Best Picture. A slightly confused Dunaway read the card, and not knowing exactly how to proceed, announced La La Land at the end of the ABC broadcast. The film’s team bounced to the stage to accept the award and the crowd applauded. Only after three acceptance speeches by the producers of the movie, a haphazard contingent consisting of stagehands and host Jimmy Kimmel stumbled onstage to correct the record: Moonlight had actually won Best Picture.

The more “real” and “gritty” Moonlight’s win over the escapist fairytale La La Land seemed to be indicative of a cultural shift, one quite serendipitously underlined by such a dramatic broadcasted moment.

In the sociopolitical climate of 2017 America, in the carnage of a tumultuous presidential race, a retro-romance film felt to voters to be in bad taste. Despite 14 nominations and six category wins, it seemed at that moment that a film would have to represent something larger culturally and politically in order to be Best Picture winner-worthy.

Given how much having the spotlight taken away from her at the 2009 VMAs influenced Swift's rebellion passion project, and given Swift and Chazelle have so many of the same artistic instincts, it is difficult to completely rule this theory out. If anything, it’s a juicy villain origin story.

The thing that makes Swift and Chazelle so cringey and easy to make fun of in this regard is the same thing that makes them such brilliant artists: their earnest commitment to what is emotionally true. They feel deeply and put force behind each frame, word, and breath in a way that builds into a cohesive, living, breathing work of art.

Babylon is expertly paced and emotionally thrilling; each camera movement and background extra is connected to the overall story. It is clear that the team behind it—the producers, casting directors, set designers, makeup artists, and so on—understood the vision of the project, taking the time to ensure that every square inch of the screen and every millisecond of expression had weight. The production is so grand yet somehow feels so simple. For the first hour and a half, I truly believed I was watching the best film ever made.

Swift’s talent lies in her ability to poetically articulate experiences with remarkable specificity, putting things humans often feel but don’t recognize into melodies. She does this through the process of trying to understand her own spread of emotions, figuring that if she is feeling them, there’s a chance many others have too. At this point, the mega-star’s daily life is vastly different from the average Swfitie’s, which results in a few less-relatable and very specific songs like “Look What You Made Me Do.” However, if she wasn’t writing about her deeply personal experiences, even the ones about how hard it is to be famous, she wouldn’t really be Taylor Swift.

On this Kanye West- and internet hater-focused album, we still get moments of clarity like, “Please don’t ever become a stranger whose laugh I would recognize anywhere.” These moments convey the menial yet consuming anxieties of life, such as navigating the early stages of a relationship or the impermanence of connection. Somehow, simple lyrics like this one help me understand my own fears and monotonous thoughts, making them tangible.

Maybe Swift and Chazelle are a bit bitter and come off a bit desperate, but it is refreshing to witness someone confident in their own truth. From this perspective, Babylon and reputation are not so much ruthless takedowns of industries as they are simply sincere and dorky little passion projects by exceptional artists.