"There is a Black Panther born in the ghetto every 20 minutes," Former Brooks Bakery, 113 East 125th St., Harlem, 1995.

Photo © Camilo José Vergara.

These Walls Talk

A brief history of wheatpasting in New York.

By Aidan CHisholm

7.12.2025

Wheatpasting—a cheap and easy method of adhering paper posters to a surface using just flour or starch and water—is quintessentially New York. The slapdash layers of air-pocketed posters on construction barricades and buildings comprise the shifting wallpaper of our city. The past six decades have witnessed the transformation of wheatpasting from a grassroots tactic charged with oppositional energy into a commercial advertising endeavor, with today’s postered walls dominated by designer colognes, streaming services, and high-end streetwear, especially in neighborhoods like SoHo and Williamsburg. The fragmented history of wheatpasting tells a history of urban transformation in New York, one that crystallizes the co-mingling of street art, activism, and commerce.

The 1960s ushered in the rise of wheatpasting as a countercultural tool of communication beyond mainstream media channels. Wheatpasting gained momentum in New York among punk bands like the Ramones and the Talking Heads, who posted flyers across downtown Manhattan promoting gigs at famed venues like CBGB. The scrappy, DIY aesthetic of these xeroxed posters particularly resonated with anti-establishment youth. As political tensions escalated in the late ‘60s with growing public discontent toward systemic oppression and state-sanctioned violence, wheatpasting expanded from promoting music to fomenting protest. It emerged as a primary vehicle for dissent, discourse, and community-building among anti-war, civil rights, feminist, and other activist groups. Wheatpasting as a collective and often anonymous tactic was primed to spread oppositional messages from disenfranchised voices.

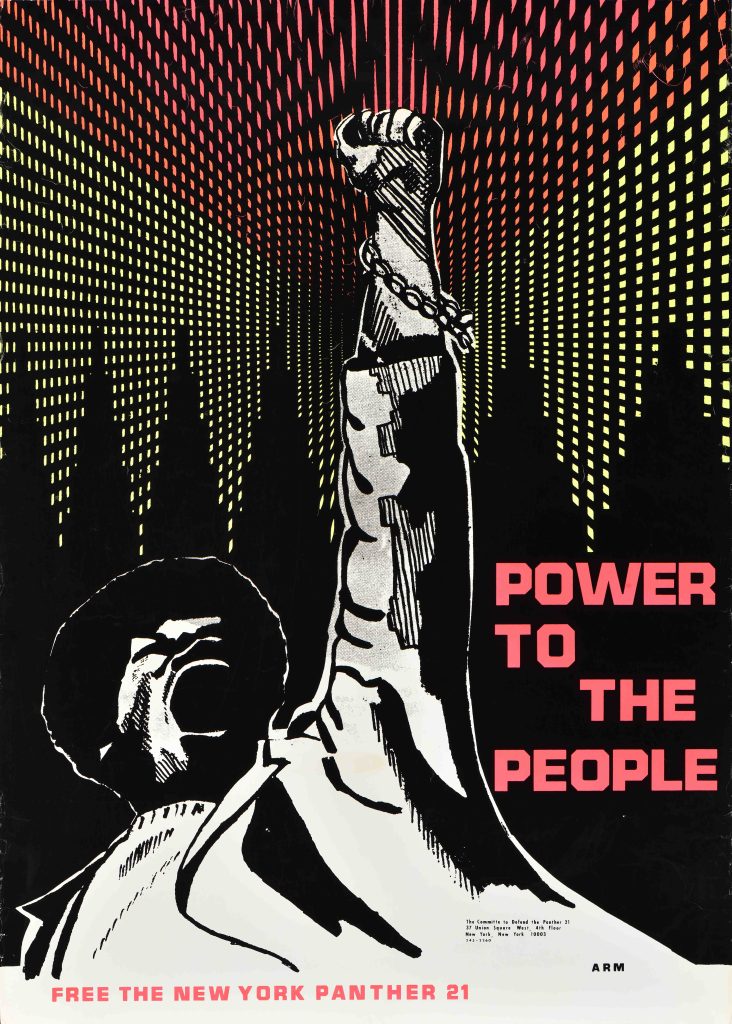

"Power to the People," 1969. Designer Unknown. Courtesy of Poster House Permanent Collection.

"Power to the People," 1969. Designer Unknown. Courtesy of Poster House Permanent Collection.

Black-led organizations such as the Black Panther Party crafted posters to wield control over the construction and circulation of their collective image as a militant group routinely villainized by top-down media outlets. With bold slogans like “Power to the People,” the group negotiated the terms of their visibility by forging a striking visual language with symbols like a raised fist and heroic images of leather-clad members donning their signature black berets. The insurgent tactics of the Black Panthers inspired other collectives like the Young Lords Party, a Puerto Rican activist group that advocated for health care reform and tenant rights in El Barrio and the Bronx.

In this late-1960s moment of fervent coalition-building around intersecting topics ranging from the hyperlocal to the international, wheatpasting afforded a quick, relatively affordable, mass-produced mode of response to shifting political demands. Posters were made collectively in workshops, often by participants without formal art training. Anarchist publishers like Come!Unity Press in the East Village meanwhile provided printing services to these local groups for free or barter. The pasting process was likewise driven by community, the reach of a particular campaign depending in part on the number of walls a group could hit in a night.

Beyond the radical content of any particular poster, the very act of wheatpasting was transgressive as an unsanctioned spatial intervention en masse, a collective gesture of defiance. A poster didn’t merely spread a message, it actively intervened within the material and social constitution of the urban landscape. Wheatpasting thus amounted to a sort of speech act in claiming the power to tangibly shape public space in real time while prompting inherent questions of accessibility and visibility in such spaces.

As protests against the Vietnam War intensified in the late 1960s, artist-activist groups harnessed the subversive potential of posters—a format long used by the government for recruitment and wartime propaganda—to insert unexpected messages. The Art Workers' Coalition (AWC), a group founded in 1969, targeted complicity within and beyond art institutions. The group including members like Hans Haacke, Liza Bear, and Carl Andre leveraged the immediacy of posters to respond to the My Lai massacre. The “And Babies?” poster incorporates a documentary photograph of a heap of murdered, partially naked South Vietnamese women and children on a dirt road. The gruesome image is overlaid with blood-red text excerpted from a CBS News television interview with a U.S. soldier, the top line asking, “Q. And babies?”, and the bottom responding, “A. And babies.” When the Museum of Modern Art rescinded its promise to co-fund the posters, the invigorated AWC rallied to print 50,000 copies themselves, some of which they used to confront the museum’s silence on the War as board members like Nelson Rockefeller actively profited from weapon sales. In a 1970 demonstration in front of Picasso’s “Guernica” at MoMA, a minister delivered a service honoring the children killed in Vietnam, while AWC members held copies of the poster up against the painting, enacting a parallel between the two visions of brutality.

Art Workers' Coalition, "Q. And babies? A. And babies.", 1970, offset lithograph on paper, overall: 25 × 38 in. (63.5 × 96.5 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Jon Hendricks, 2017.10, © 1970 Irving Petlin, Jon Hendricks, and Frazer Dougherty.

Art Workers' Coalition, "Q. And babies? A. And babies.", 1970, offset lithograph on paper, overall: 25 × 38 in. (63.5 × 96.5 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Jon Hendricks, 2017.10, © 1970 Irving Petlin, Jon Hendricks, and Frazer Dougherty.The AWC simultaneously recognized the need to reach beyond the insular white walls of the art world to fuel broader public outrage against the atrocities committed by U.S. forces. By excerpting this image from the mainstream media to then reframe and recirculate the adapted visual as wheatpasted posters, the group indicted not only U.S. imperialism, but also broader cultural complacency. The sheer number of posters rendered the brutality of the War unavoidable, embedding the visual in the public consciousness, if only for a moment before the posters were covered or stripped. As a particularly effective instance of pre-internet virality, this campaign established a sort of blueprint for the potentials of wheatpasting as a quick, crucially repetitive mode of public provocation.

Groups like the AWC and its many specialized offshoots vehemently denied conservative fantasies of art as neutral or apolitical while calling into question the political responsibilities of cultural institutions. The low-brow status of posters promoted the anti-capitalist appeal of such grassroots interventions distanced from the elitist domain of “fine art” at a moment when many artists felt disenfranchised by the aloof formalism of Conceptual Art and Minimalism. The ephemerality of the mass-produced medium meanwhile countered standard archival imperatives of durability, provenance, and individual authorship.

In the 1980s, the HIV/AIDS crisis spurred a resurgence of wheatpasting with fervor recalling the tactics of the 1960s. Groups like ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) leveraged this charged form of direct action to protest lethal government neglect in the face of mass casualties and rampant homophobia. Wheatpasting operated in conjunction with performative interventions like sit-ins, pickets, street patrols, and rallies—events often publicized by posters. Such tactics confronted the spatial restrictions enforced under Mayor Ed Koch, such as the closure of gay bathhouses and clubs in 1985, which marked the targeted decline of the more visibly robust gay culture of the 1970s.

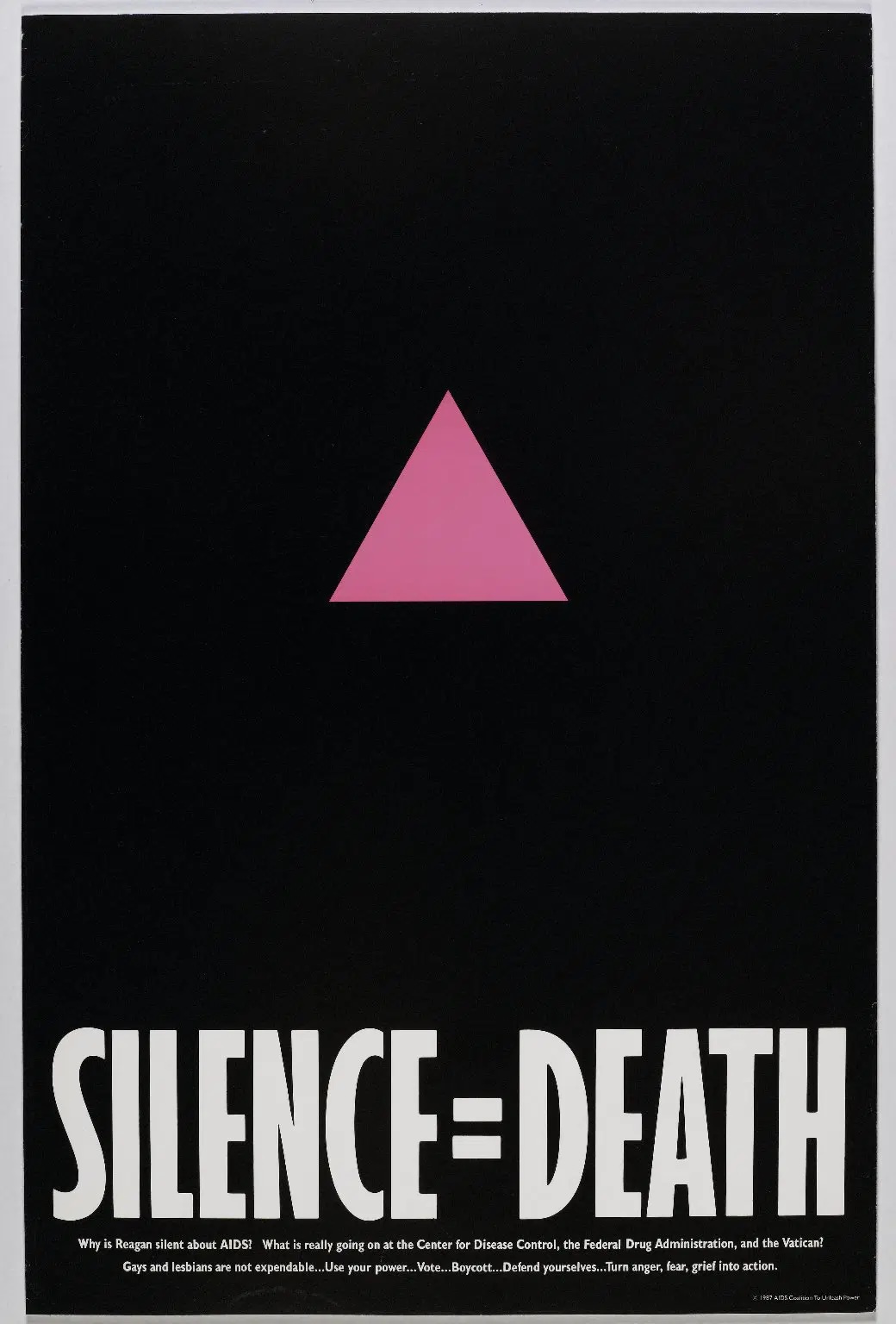

SILENCE = DEATH Project (Avram Finkelstein, Brian Howard, Oliver Johnston, Charles Kreloff, Chris Li. SILENCE=DEATH, 1987. Offset lithograph, sheet: 33 9/16 × 21 15/16 in. (85.2 × 55.7 cm) mount: 33 9/16 × 21 15/16 in. (85.2 × 55.7 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Robert Thill in honor of Robin Renée Thill Beck, 1998.109. © artist or artist's estate. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum).

SILENCE = DEATH Project (Avram Finkelstein, Brian Howard, Oliver Johnston, Charles Kreloff, Chris Li. SILENCE=DEATH, 1987. Offset lithograph, sheet: 33 9/16 × 21 15/16 in. (85.2 × 55.7 cm) mount: 33 9/16 × 21 15/16 in. (85.2 × 55.7 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Robert Thill in honor of Robin Renée Thill Beck, 1998.109. © artist or artist's estate. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum).

Gran Fury, a branch of ACT UP, drew inspiration from the AWC and later artist-activist collectives like the Guerrilla Girls in designing the now iconic “SILENCE = DEATH” poster, which drew on advertising aesthetics to maximize visibility within an increasingly saturated visual economy. The eye is immediately drawn to the sole pop of color within this bold graphic scheme: a pink triangle associated with the persecution of homosexuals in Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s, which was then reappropriated during the gay liberation movement of the 1960s. The contrast of the white block letters against the black background heightens the visual intensity of the powerful rhetorical equation, “SILENCE = DEATH,” which renders the passerby complicit in the mounting death toll. The group drew from theories of détournement—French for “hijacking”—in mimicking mass-marketed media only to deliver unexpected political messaging.

Avram Finkelstein and Vincent Gagliostro, artists associated with ACT UP, likewise employed this strategy in their “Enjoy AZT” poster, which emulated the iconic graphics of Coca Cola to critique the high cost of azidothymidine (AZT), the first FDA-approved treatment for HIV/AIDS. This tactful reworking of Coke’s ultra-iconic logo effectively called into question the exploitative capitalist underpinnings of the pharmaceutical industry.

The populist appeal of the poster as a ubiquitous format with commercial connotations ensured the reach of the campaign beyond the gate-kept art world. At the same time, these activist collectives rejected the capitalist logics of individual authorship that shape the art market, instead encouraging the free reproduction of the visual sans copyright. In the context of such dire institutional failures, the serial repetition of these posters across city walls was an urgent testament to the underlying formulation and mobilization of community, a tangible demonstration of a collective political commitment exceeding any individual. The spatial implications of wheatpasting were particularly important for groups like fierce pussy, a collective that promoted the visibility of lesbian identity through campaigns reclaiming the language of street harassment on the streets.

Amid a wave of privatization in the 1980s following the fiscal crisis of 1975, wheatpasting was simultaneously leveraged to address the city’s deepening housing crisis marked by mounting threats of displacement in disinvested neighborhoods like the Lower East Side. Political Art Documentation and Distribution (PAD/D), an artist-activist collective co-founded by Lucy Lippard, Margia Kramer, Gregory Sholette, and others in 1980, recognized the streets as the prime venue through which to contest a spatial phenomenon like gentrification. With Art for the Evicted: A Project Against Displacement in 1984, PAD/D wheatpasted satirical posters protesting rent hikes, real estate speculation, and the displacement of working-class communities across downtrodden Lower East Side facades at sites with particularly fraught histories. The group dubbed one array of posters outside a vacant tenement near Tompkins Square Park “Guggenheim Downtown.”

"Out of Place: Art For the Evicted," 1984. Courtesy Gregory Sholette/Dark Matter Archives.

On one hand, the very act of wheatpasting at these contested sites constituted a spatial assertion against commodification, with posters calling for local artists to join the resistance. And yet such in protesting gentrification, certain PAD/D members recognized the painful paradox that artists risked inadvertently fueling the very transformations they opposed by attracting developers drawn to the cultural caché of the post-industrial neighborhood. As galleries followed artists to the East Village, rents soon rose, and the radical potentials of art-as-activism were complicated by the complicity of such interventions in the displacement of local communities, often including the artists themselves. Through wheatpasting, PAD/D offers a valuable case study in the complicated, at times ironic positioning of artists amid rapid gentrification in the 1980s and beyond.

In the 1990s, wheatpasting began losing its radical edge in the context of real estate-led urban “revitalization.” The rise of neoliberal governance fueled the very processes critiqued by PAD/D, which simultaneously limited the viable spaces for unsanctioned posting, just as the internet provided new venues for public engagement on an unprecedented scale. Meanwhile, Mayor Giuliani’s “Quality of Life” mandates targeted non-commercial wheatpasting as a misdemeanor offense. In a sense, the increased policing of grassroots posting, along with graffiti and other forms of street art, suggests the oppositional threat of such ephemeral interventions while signaling the broader intensification of the de facto police state.

Simultaneously, corporations recognized the potential of wheatpasting as a form of advertising with an aura of “authenticity” or “downtown cool.” Giuliani permitted the commercial usage of the very techniques criminalized as vandalism under his “broken windows” policies, resulting in the sanitization and rebranding of the grassroots tactic as “guerrilla marketing.” Luxury brands and mega-corporations that had favored more polished advertising formats in previous decades increasingly adopted the homespun look of xeroxed posters, simulating the grit of resistance minus the politics. This co-optation of wheatpasting reflects a broader pattern of urbanization with the aestheticization of countercultural practices by the mainstream. If wheatpasted posters once embodied a statement of visibility and a claim over public space by marginalized groups, the commercial posters today are a reminder of the privatization of the urban landscape as a tool for capital accumulation under neoliberalism.

In terms of sheer volume and visibility, advertising undoubtedly dominates pasted walls today. Yet despite the thorough commodification of wheatpasting, we can glimpse its grassroots legacy on rare occasion when a call for climate justice or Ukrainian solidarity appears sandwiched between advertisements for a video game console and a fat-free yogurt. The Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011 invites us to consider the continued importance of ephemeral protest materials, in this case cardboard, in our so-called Internet Age. Recalling the direct action tactics of HIV/AIDS activists, the use of this transient, often discarded and repurposed material lent a sense of urgency and precarity through associations with dispossession. In the past decade, the Black Lives Matter movement has spurred the use of posters to protest police brutality with iconography adopted from the Black Panthers, such as the raised fist and the crouching panther. In 2020, a surge of nationwide protests following the murder of George Floyd coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbated systemic inequalities while further complicating distinctions between public and private space. On boarded-up storefronts in SoHo, posters of kneeling Colin Kaepernick appeared alongside flyers urging mask compliance. Further uptown at Lincoln Center, artist Carrie Mae Weems’s “Resist COVID/Take 6!” campaign foregrounded the disproportionate toll of the pandemic on BIPOC communities.

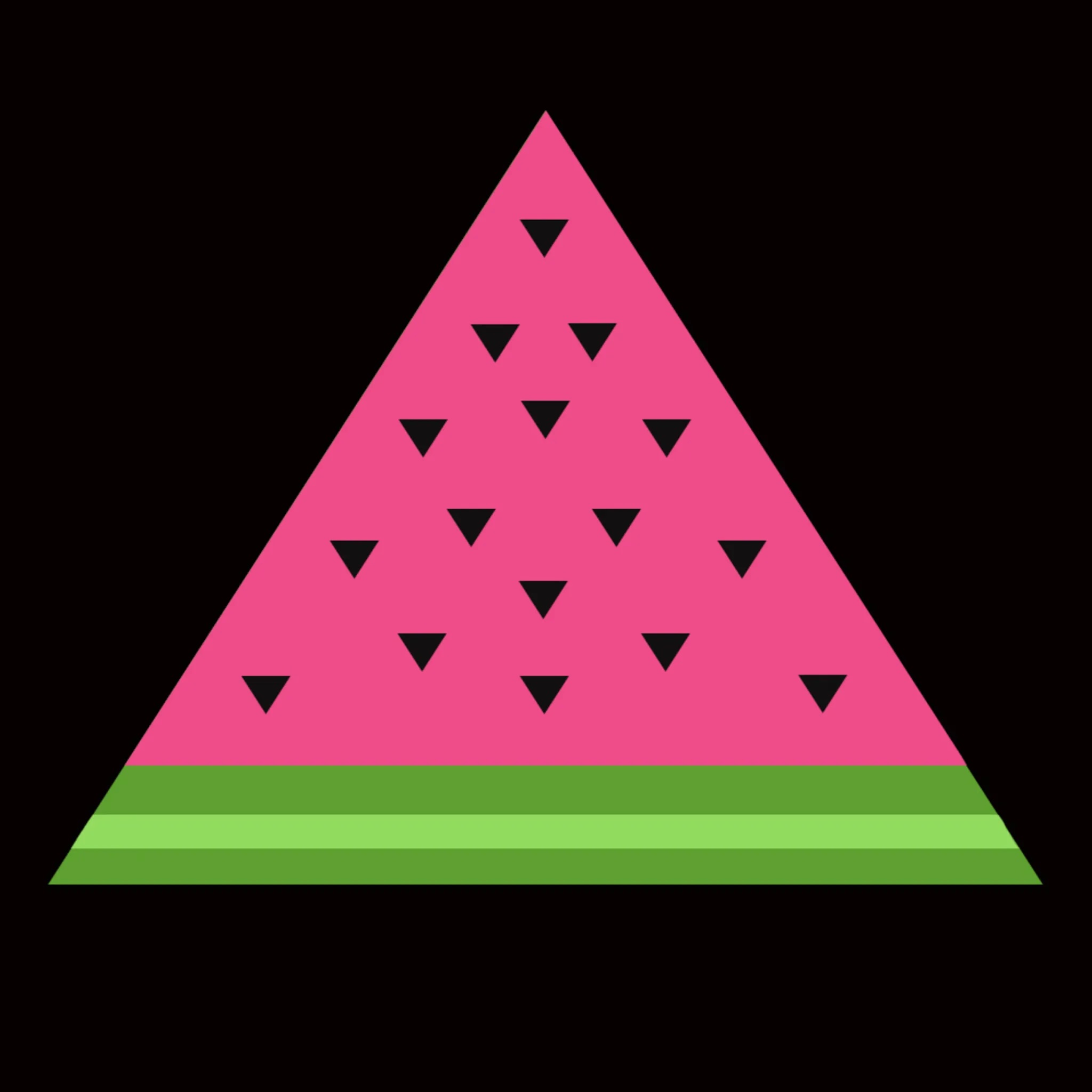

ACT UP artwork in solidarity with Palestine by Shawn Escarciga

More recently, members of ACT UP transformed the pink triangle icon long associated with queer resistance into a watermelon, a symbol of Palestinian solidarity. This adaptation of the “SILENCE=DEATH” poster introduced during Pride month in 2024 speaks directly to queer communities while drawing on the watermelon’s viral appeal as a transnational protest icon. ACT UP models the potential for reflexive engagement with histories of protest through posters imbued with the affective resonance and collective cultural memory of earlier political efforts. Wheatpasting is no longer the fastest, cheapest, or most far-reaching tactic, yet the ongoing commitment to this format by groups like ACT UP asserts the ongoing importance of embodied, site-specific interventions in public space, perhaps together with social media messaging.

Wheatpasting’s resistance to the archive dovetails with its resistance to authority as part of its power. This fugitive quality has rendered wheatpasting so potent in prioritizing immediacy over longevity. The fragmented history of wheatpasting does not offer a neat, linear narrative, but rather prompts questions about the potential of the street as an arena for political intervention in the context of digitization—questions that seem more urgent than ever within the late-capitalist infrastructure of the city today. Although the commodification of wheatpasting has hindered its radical potential, the legacy of the grassroots medium always already intertwined with commercial aesthetics invites us to consider how we might adapt the insurgent tactics of the past to the structural conditions of the Internet Age in a city increasingly dominated by private interests.

”SILENCE=DEATH” posters in New York City, February 1987. Photo by Oliver Johnston, courtesy Avram Finkelstein.

”SILENCE=DEATH” posters in New York City, February 1987. Photo by Oliver Johnston, courtesy Avram Finkelstein.Further reading:

Colin Moynihan, “When Posters Were the Samizdat of the Lower East Side,” The New York Times, May 18, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/18/arts/when-posters-were-the-samizdat-of-the-lower-east-side.html.

Deborah Gould, Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight Against AIDS (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Gregory Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (London: Pluto Press, 2011).

Poster House, “Black Power to Black People: Branding the Black Panther Party,” March 2–September 10, 2023. https://posterhouse.org/exhibition/black-power-to-black-people/.

Tara Jean-Kelly Burk, “Let The Record Show: Mapping Queer Art and Activism in New York City, 1986-1995” (PhD diss., City University of New York, 2015).