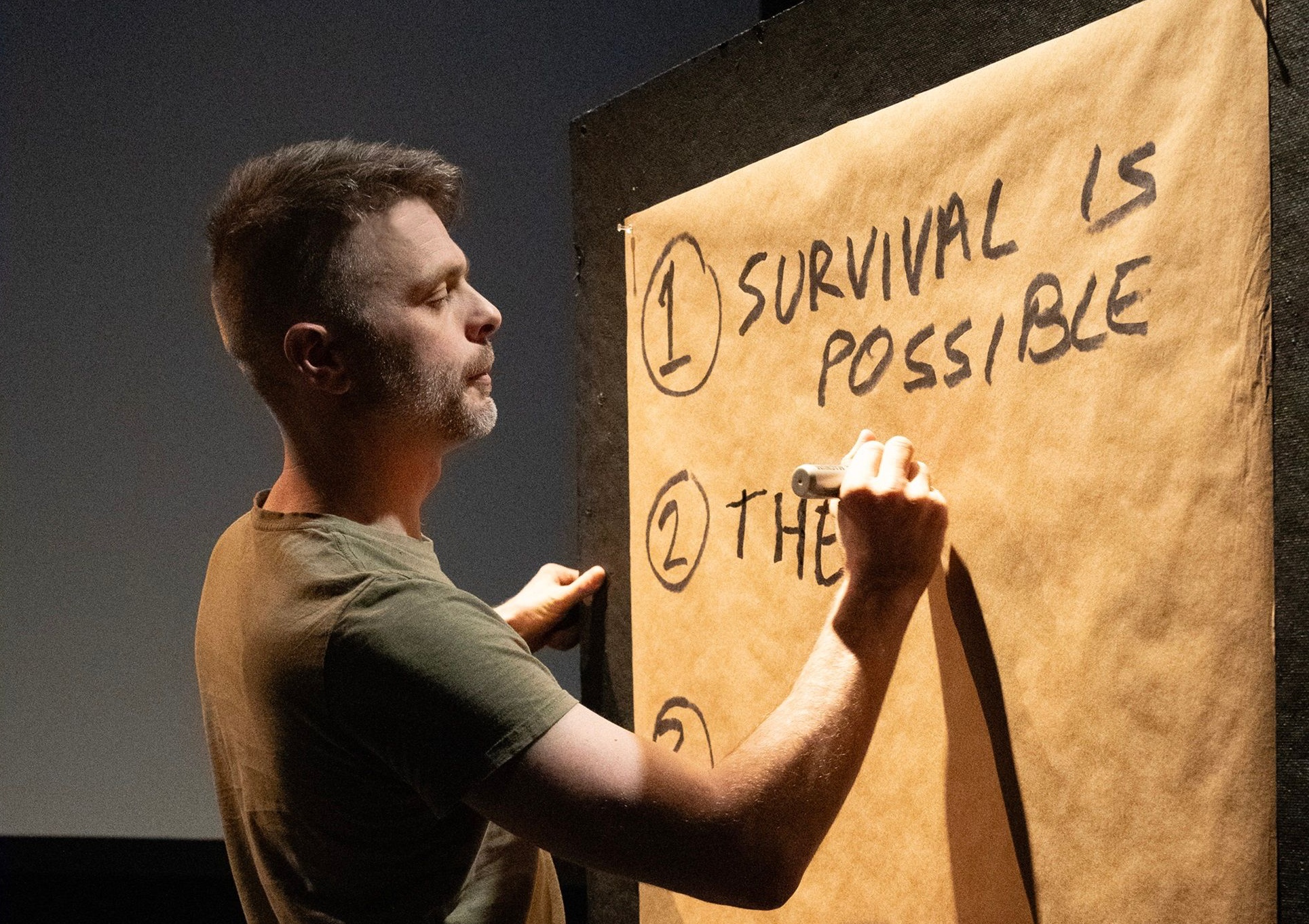

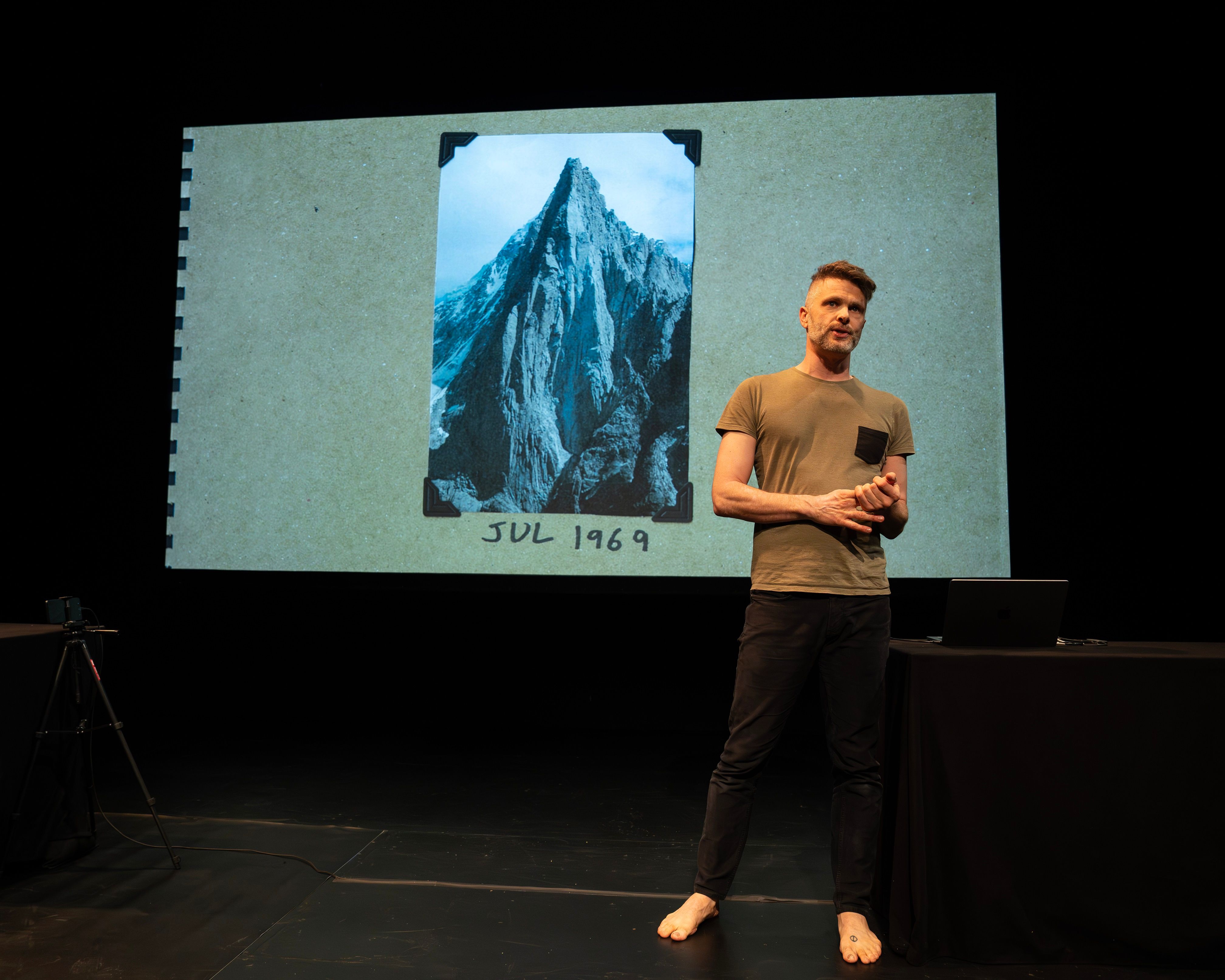

David Finnigan performing Deep History. All photos by Joan Marcus.

Deep History Provides a Path for a Collective Future

a one-man show by david finnigan explores the roles we all play in facilitating climate change.

By Ciaran Short

11.04.2024

Normally, I would do anything possible to avoid subjecting myself to a white man yelling at me for an hour. However, I also like to try new things and thus I, a complete theater imbecile, ended up participating in a writing lab about theater, getting offered free tickets to David Finnigan’s Deep History, and attending a play in which Finnigan, a white man, enthusiastically addresses the crowd for over an hour about climate change.

I went into this performance completely blind. When I settled into my seat, opened the playbill, and saw only one person under the cast section, I was a little concerned. The thought of a one-(white)-man play most definitely did not excite me. Then I noticed the audience filling in around me: elderly white couple after elderly white couple entered the room. Before long, I was distraught, surrounded by perfectly pleasant white folks rearing to enjoy some top-notch off-Broadway theater. Stale discussions of traffic, overrated five-star restaurants, and the weather flooded the air.

As I attempted to appear non-threatening enough to divert attention yet threatening enough to not invite conversation, I scoured the playbill over and over, even reading the fine print on the advertisements. A warm sensation sizzled up in the back of my neck as I desperately tried to quell the anxious thoughts repeatedly telling me I didn’t belong. Suddenly, the lights began to dim. I dug my nails into the arm rests and settled in. It’s just an hour. I can do an hour.

David Finnigan took center stage, and Deep History began. When he played Caroline Polachek’s “So Hot You’re Hurting My Feelings” from a laptop and likened it to climate change, my dread quickly softened into skepticism. A barrage of giggle-worthy quips and asides further dismantled my biased distrust and, by the time Finnigan transported us back 75,000 years in human history, I was fully in it.

The narrative structure of Deep History didn’t follow that of a traditional story arc; it slowly swelled and swelled before falling into an all-out sprint of chaos, heartbreak, and disorder, leaving both the audience and Finnigan out of breath. Part science class and part dramedy, Finnigan’s extensive knowledge base was enriched by his vulnerability and raw emotional admissions.

Conceptually, I know climate change is an urgent issue. But when I think about it long enough, that urgency only manifests as anxiety. Due to a feeling of helplessness, I compartmentalize, choosing to focus on more localized and immediately tangible issues like housing justice or police brutality because there are outlined demands for both individual and systemic national action. Substantial climate action, however, requires global action—although local interventions can incrementally make a difference, it’s hard not to feel fatalistic when any positive contributions can be completely offset by a determined-enough party across the street, country, or globe. So as a relatively broke artist living in the liberal bubble of New York City, it feels like I’m the last person capable of making a significant impact—and that’s precisely the problem, which Finnigan masterfully highlights in Deep History.

David Finnigan performing Deep History.

It’s easy to shrug off climate change as someone else’s problem, especially in New York: other people are the victims, other people will find the solution, other people should be doing something. Whether it’s “other people” in the sense of time or place, it all revolves around a rejection of responsibility and decentralization in the story of climate change. How Finnigan challenges and subverts this notion is by creating the story of a universal human being who is simultaneously every person in history, every person in the audience, and himself.

Finnigan offers himself up essentially as a sacrifice to facilitate the audience's understanding of their own role in either proliferating or maintaining the status quo of climate denial or climate change. As the narrator and protagonist, Finnigan moves beyond comedic self-deprecation to put his own biases and shortcomings on full display for analysis and scrutiny as he details his experiences with the wildfires that devastated much of Australia in 2019 and 2020. By centering his own sympathetic story and exploring how a state of desperation drew him to an individualistic mindset, he invites the viewer to hold a mirror up to their own life. Rather than coming from a place of judgment or admonishment, Finnigan opts to reinforce the fact that the collective “we,” as in all of humankind, are both all responsible for and capable of making a difference to allow for our continued survival.

Yet Finnigan’s optimism is rooted in genuine pain and fear, thus preventing him from succumbing to empty platitudes and toxic positivity that can belittle the real and present dangers of climate change. In fact, he offers no real answers or solutions, and this humble honesty is exactly what sets Deep History apart as a socially engaged piece of art. I’m a firm believer in art having the potential to prompt and encourage social change in the realms of awareness and empathy leading to direct action. How this takes shape and form, however, often is an amorphous and unclear path that hinges on understanding one’s audience. In Deep History, Finnigan's approach to taking action as well as storytelling is the same as the message I took away from the play. Finnigan has only one audience he must cater to, and that’s simply people. In turn, at its most basic level, the solution to climate change is dismantling the idea of the other. Finnigan’s acknowledgement that climate change will likely most adversely and immediately affect those who are already marginalized, combined with his effort toward unification by creating an imagined universal human as the story’s protagonist, offered a level of nuance that is rare when speaking about such a polarizing issue. If a middle-aged Australian man can bring me to tears after an hour of talking, then with a little effort, I could also come to connect with the sea of old white people I found myself so uncomfortable being around on a Sunday night; they too, likely having money, influence, and power, will hopefully see this play and seek to reach outside of their known worlds and empathize with the millions of people currently affected by climate catastrophes who aren’t able to tell their own stories.

As we all walked out of the Public Theater on a beautiful autumn night, I looked to my neighbors and felt a sense of comradery. Although they were waiting for taxis and I was scurrying away to the nearest unmanned subway station to hop the turnstile, the separation in destination was superficial—we were all together on a shared journey in the preservation of human history and our collective future.

See Deep History at NYC’s Public Theater through November 10, 2024.