Maya Man in her studio. Photo by James Kramer.

An Interview with Maya Man

The artist explores what it means to be a girl online.

By Nolan Kelly

3.27.2025

Maya Man is an artist living in New York City and making work about what it’s like to go online today. Her many websites and digital projects tend to explore algorithmically suggestible content (light pink affirmations, cute red shoes) through an added layer of auto-generation, so that the whole feed becomes slightly uncanny. This process, in which the vast digital mechanism that orders so much of our mental activity seems to stretch or melt without ever compromising its friendly and attractive surface, feels apt for the internet environment of today, where it’s no longer really possible to overload the system or fall off the edge of the map.

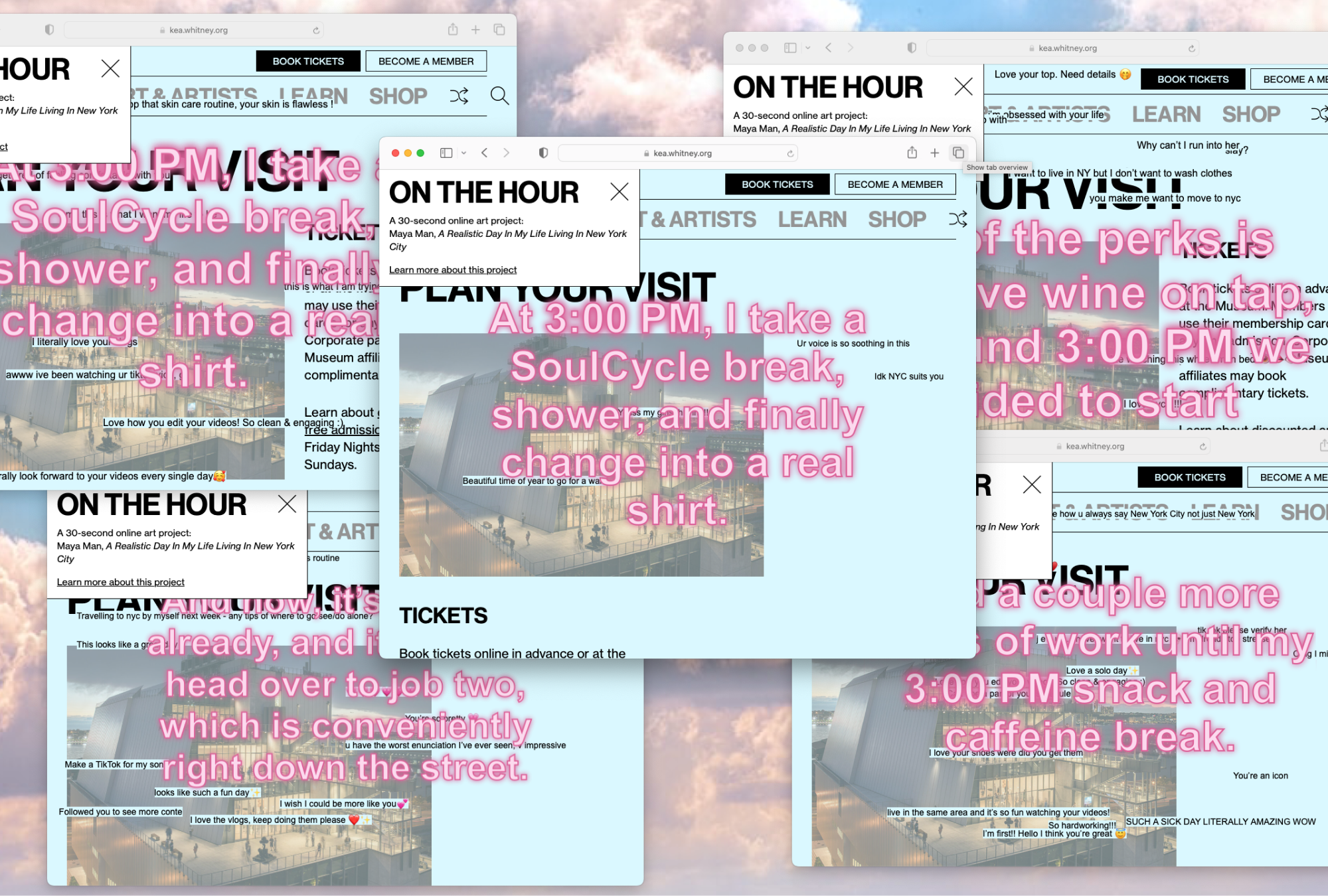

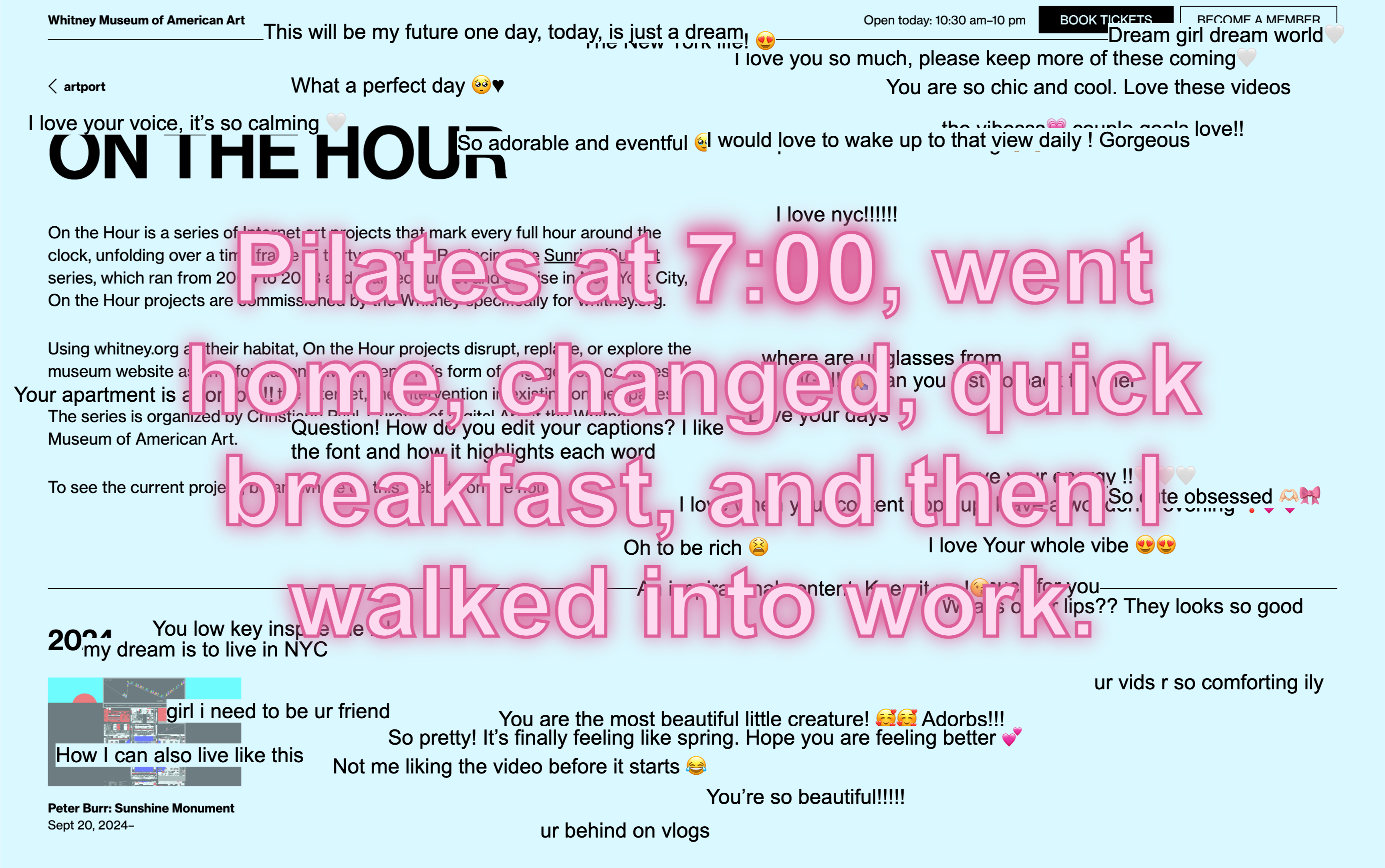

Maya’s ultimate aim is to explore subjectivity and the manufacture of identity as it happens, to all of us, online. She’s obsessed with micro-trends and subcultures and takes an analytic approach to identifying patterns of behavior that create ripples in the stream. Last year, her project A Realistic Day In My Life Living In New York City appeared on the website of the Whitney Museum, taking over its digital interface for thirty seconds at the top of each hour to play narrative updates from real “day in the life” TikToks in a time-synced manner. There may be satire in this project (the title’s use of “realistic” feels particularly tongue-in-cheek), but never cynicism. Maya operates with a deep respect for the millions of people who open their phones each day with the desperate urge to see and be seen, who entertain each other for entertainment’s sake. The emotional resonances these strangers hold for one another are real.

Maya Man, A Realistic Day in My Life Living in New York City.

Off screen, Maya codes, collects gift-shop keychains, and sews her patchwork pieces at HEART, her SoHo studio space that was also (until recently </3) a gathering place for like-minded internet people. I met up with her there in January to talk about what makes her scroll.

COPY: Correct me if I’m wrong, but I'm guessing you probably went online starting when you were pretty young.

MAYA MAN: Yeah, definitely. I grew up in very suburban central Pennsylvania, in a town called Mechanicsburg. It wasn’t really near any big city. And so I used to love being on the internet, especially in the early days of YouTube and Tumblr. To me, the internet was where the world happened, where culture was. I wanted to be part of that and loved the participatory nature of it. I would make so many movies on my Flip Video camera, edit them in iMovie, and upload them to YouTube. No one was watching them, but I would see other young girls in their bedrooms doing the same thing, and that was exciting to me. It made things feel possible.

Our generation, even on a micro-level, we’re really the trailblazers of that totally new form of interaction.

I feel like my idea of being in the world and my idea of self was always very tied to being online. And it's a generational thing, but something I've been thinking about lately is why I have plenty of friends my age who are not super online. I'm curious about my instinct to really grasp onto it as a kid, you know, like what it was about being online that I aligned with so deeply.

It's funny, I think I grew up very restricted from going online because my mom was a psychologist. It’s clear that some part of it is innately involved in the development and wiring of a young brain, and then there’s also something totally voluntary and identifiable in it to certain degrees.

It also used to be such a decisive act to be like: I'm going online, I'm logging on to my parents' computer. And I think now, like everything, the internet feels so much more immersive. It feels so much more like the air that I breathe.

Did you feel like what you were making was art when you were uploading that stuff as a kid?

No, growing up, I never thought of myself as an “art kid.” I really came to artmaking through programming. I really enjoy programming. I'm probably the happiest when I'm actually coding something. So I studied computer science, and after my first year of college, I met some people who were interested in making artwork with code. And that really opened my mind to what was possible with programming.

Was that through some formal community of artist-programmers?

It was really through Lauren Lee McCarthy, who's an amazing artist. After my first year of college, I was doing a program called Google Summer of Code, where you're matched with an open-source organization for a month. I was matched with the Processing Foundation, which holds the library for Processing, the software made by Casey Reas and Ben Fry in 2001, which is a Java-based programming language that a lot of artists have used to make artwork. So there was this really large community around Processing of artists who were interested in specifically software-based work, which is something that’s been happening since the early days of computer art in the 60s and 70s. And then after Processing came p5.js, which is a user-friendly JavaScript library made by Lauren Lee McCarthy. Lauren was just starting to work on p5.js, and she was hosting the first conference in Pittsburgh that summer in 2015, and she invited me to come along as an intern. I went and I met so many artists who were excited about code-based work. Lauren was really thoughtful about the p5.js community she was building and wanted people to feel welcome who were beginners. I'm really grateful she welcomed me there because, looking back, I was like a teenager rookie computer science kid. But it really was life-changing for me because also, in Lauren's work, she's very critical of technology, and she's not making work that's purely celebratory or just technically complex. So that was really formative.

One of the things that I find really interesting about your work is that if it critiques internet culture, it tends to do it from the inside. A lot of it looks, on the surface, like the typical consumptive-productive, proof-of-life posting that we all do online.

I like to take aspects of internet culture and filter them through some sort of system that I'm building, whether it's an algorithm or a conceptual framework that I design, and twist it just a little bit. Something that I’ve grappled with, even when I go back and read diaries that I had when I was in middle school and high school, was thinking about the way that I use the internet. I had a lot of guilt and shame associated with the way that I posted because I was constantly recognizing this instinct in myself to perform an idealized, aspirational version of myself in my life. I felt so guilty about it and felt like it was deeply evil in some way, but I also really liked doing it. So I think when I started to make artwork, I was interested in it existing in this kind of ambiguous universe where it was recognizing the fun and indulgence and joyful aspects of being online, but at the same time, I know the way that I feel about the work is that it's commenting on something that to me is very dark, very grotesque, very ugly. That's a tension that I always want people to be able to access in my work, and a worry I constantly have is that people are going to read it on the surface level and not be able to see the darker sides of it.

I think that’s a very common feeling, to be really critical of your online activity or see something wrong with it. I'm curious how you think about the balance of being an artist who makes work on that condition while also being a pretty straightforward digital version of yourself. It’s not like there’s some other person you hide behind when you post. You’re a girl online who's making work about what it’s like to be a girl online.

Sometimes I sense that people want to read the person that I post as online, like if I'm posting a dumb dancing TikTok or whatever, as coming from a disingenuous place. I think people want to separate their idea of an artist, who is smart, and the girl online, who is dumb. And I feel that tension a lot in the way that people want to read my work as if it's impossible to reconcile the two as the same person.

When I think about posting online as an artist, I think a lot about “Dispersion” by Seth Price. It’s an essay that was published in the early 2000s, and so he has this kind of optimistic view of what the internet can be for artists. But I really like being able to reach people through channels that go outside of the museum and gallery system, and it's important to me to reach people who are not necessarily seeing themselves as interested in contemporary art. I grew up in an area where the people around were not interested in contemporary art; no one was part of that scene or that universe. But I like that online, I can ideally reach people with the work who are interested in what I'm talking about and who are interested in the subject matter, but who probably aren't going to a gallery on a Saturday afternoon.

It also feels like you’re creating more space to celebrate the earnestness of being a person who uses the internet. I think we often go online in a sort of ironic fashion, or include a level of irony there just to preserve the danger of like... feeling embarrassed? And I feel like you're almost maybe adding one more layer to that, but in a way that allows more of a space of earnestness to come in.

Yeah, I feel very earnest about my relationship to being online, but also very critical. I think irony has evolved to be a really ubiquitous defense mechanism for people in the way that they use the internet because earnestness can be so vulnerable, and the internet is not necessarily a safe place. I really believe in nuance when talking about the internet, and that's also why I'm very hesitant to make sweeping statements. I think people tend to want to veer a conversation about the internet now toward “everything is bad” or “everything is good.” And I think those are impossible claims to make.

Maya Man, A Realistic Day in My Life Living in New York City.

Maya Man, A Realistic Day in My Life Living in New York City.