Never Rarely Sometimes Always (dir. Eliza Hittman)

Reach Out Your Hand and

I Promise to Take It

My body felt like a traitor, as if it had suddenly, unbeknownst to me, exposed some insidious truth within.

By anna-lena dressman

8.24.2022

I was 15 when I sat with my friend in a McDonald’s bathroom and helped her wait out the results of the cheapest pregnancy test we could find.

I was 18 when I was roofied in a club and, because I didn’t know what else to do, took my first pregnancy test the following week.

I was also 18 when I walked with another friend to a pharmacy and bought her Plan B after a hookup she realized she no longer wanted halfway through but kept going anyway.

Each time resulted in a sigh of relief. Not pregnant.

Then I was 23, sitting in a cafe in Paris, reading a New York Times notification that the Supreme Court had overturned Roe v. Wade in one fell swoop, terminating the constitutional right to abortion.

Simone de Beauvoir writes that “one is not born, but becomes a woman.”

I think that right there, at that moment, I became one.

I instantly reviled at this new identity that was thrust upon me and considered just becoming Parisian, becoming anything but myself and the burdensome weight of my own body. I spent the plane ride back to the US wishing I could dissolve into thin air halfway across the Atlantic Ocean and never have to be anything or anyone again.

In de Beauvoir’s terms, being a woman is something like living in front of a trick mirror. You go about your life, going to work, going to college, dancing with friends, reading, writing, falling in love. All the while, you’re unaware of the jeering audience on the other side of the glass.

When Roe was overturned, it felt like the trick mirror had shattered. No longer could I live my carefree, unperceived life. I was now capital-w Woman in the eyes of the world. A body, a vessel for life. I spent weeks overcome by an uncontrollable desire to cry and cry and cry. Maybe the tears were washing out some inexpressible feeling, or maybe I was trying to shed myself, make myself a little smaller. My body felt like a traitor, as if it had suddenly, unbeknownst to me, exposed some insidious truth within.

All the while, I kept thinking of a movie I’d seen at the Metrograph a few weeks earlier, Eliza Hittman’s Never Rarely Sometimes Always, which the theatre had shown as part of an abortion-in-film series. The film centers around 17-year-old Autumn Callahan, who, facing an unplanned pregnancy and restrictive abortion laws in her home state of Pennsylvania, embarks on a trip to New York City to get an abortion. Autumn is joined by her cousin Skylar, and the film sinks its teeth into their unspoken yet unshakeable bond.

The scene that sticks with me most is not the abortion itself, but a scene where the two girls are trying to get a guy to give them money for the bus home. He acquiesces, but implies that it won’t be down to pure altruism. He’s been trying to get with Skylar all night, and now, he will.

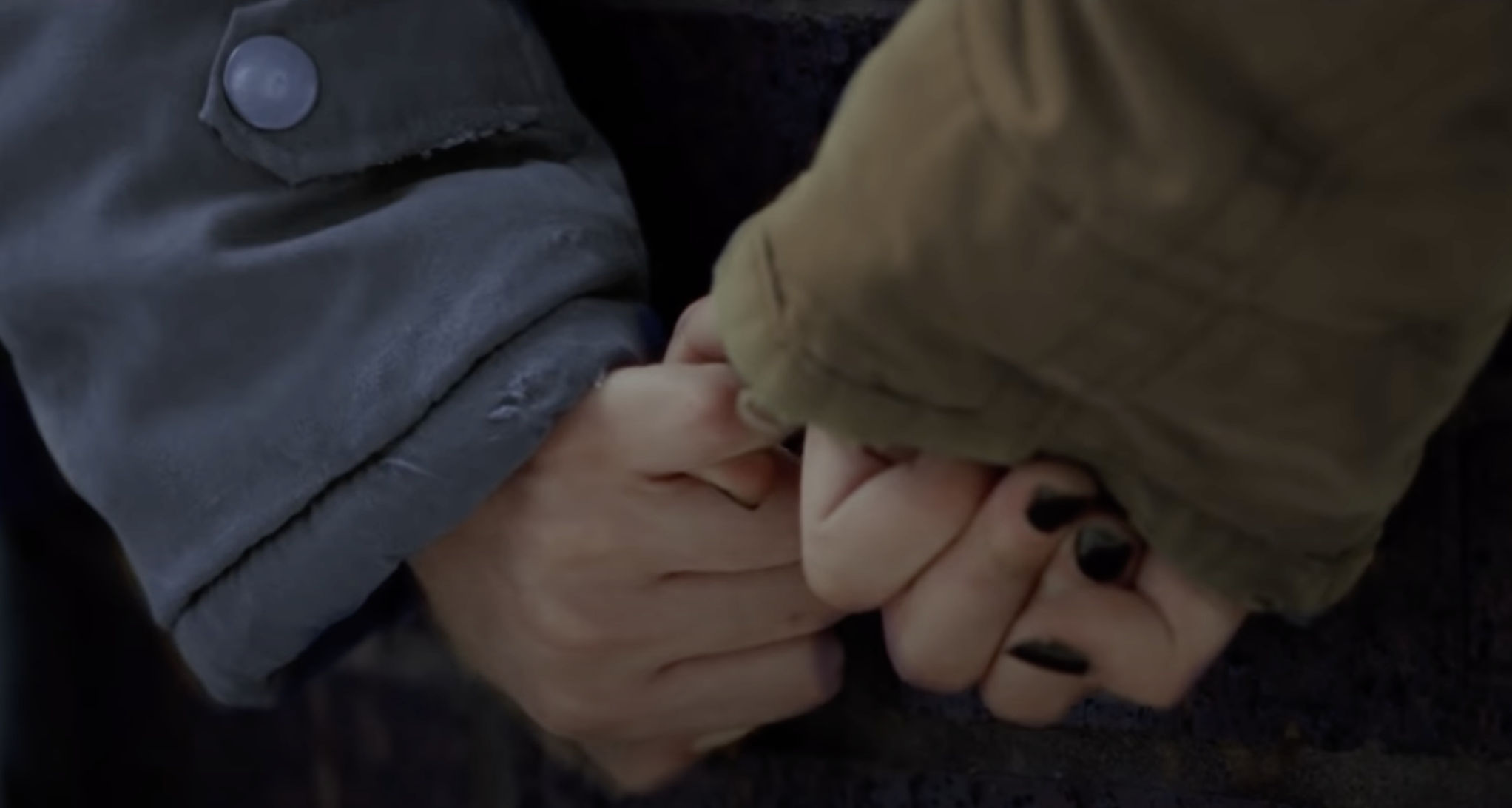

The scene goes like this: In a dimly lit, low-traffic corridor of New York’s Port Authority Bus Terminal, the guy has his tongue down Skylar’s throat, pushing her against a column. On the other side of the column stands Autumn, her hand reaching out to Skylar. Slowly, the camera pans in on their fingers interlocking in a spellbinding moment of solace, togetherness. The guy is too enraptured with the moment to realize that he’s not central to this scene.

The scene stuck with me most because in it, Hittman subtly turns the trick mirror onto the Man. Under the unforgiving gaze of the camera, the audience focuses on the guy as a body, not a person, in a manner reminiscent of the endless shots we see of women’s legs or torsos in the rom-coms of the early 2000s. He’s not alone—almost all the men in the film come across as brutish and creepy, things to be tolerated, not respected.

In a way, it’s empowering to see men depicted in such a lowly way. But Hittman’s main characters, Autumn and Skylar, don’t extract their power from the despicable behavior of the men around them. Instead, their power is more inherent to them: it exists because they do and holds because they stick together.

So much of the language around Roe v. Wade has been about power, and the tug-of-war between our society’s conception of Woman and the real people simply trying to figure out how to live their lives. While it can feel vindicating to fantasize about a reverse-objectification of men, for men to live in a woman’s shoes for a day, Hittman’s film reminds us to not be lazy and to think beyond the existing relations of power. Her film is a testament to friendship as a remedy for the malaise of being a woman.

So much of the film rests on the unspoken moments between Autumn and Skylar. These scenes are rife with that quiet magic of friendship that goes beyond spoken words and reminded me of all the times I’ve sat around with my friends in silence. Some moments were serenely happy, lazing on the couch sipping tea. Others were filled with fear, in a McDonald’s bathroom, waiting out a pregnancy test. I’ve never been able to put that feeling into words, but Hittman figured out to show what I’ve felt. This is real love, in a way family or romantic relationships can never be. It’s what wills me to live on days I don’t want to and makes the happiest days even brighter.

In a similarly inexplicable way, life inches forward. It’s now been a few weeks since Roe was overturned, and I still feel like I took the red pill by accident. That scene around the column plays on repeat in my head, and I think that if I play it enough, I can rewind to the time the movie was set, when Roe was still intact.

I go to work, swim in the ocean, and talk to my Mom. I have sex and no longer think about babies and bloody surgical devices. I start worrying about climate change again. I feel lucky to live in a state where abortion is legal, and where I can even conceive of moving forward, inch by inch, day by day. There are still things to look forward to.

But some days, I feel like I need to press pause or rewind. On those days, I know what to do. I’ll call my friends. I’ll reach out my hand, and know that I’m part of something outside myself, something bigger.

That’s the one trick I have up my sleeve.

Never Rarely Sometimes Always (dir. Eliza Hittman)