donate to our end of year fundraiser <3

![]()

@whataboutbunny

Silence of the Dogs

A dog rose to international fame in the 1980s for his ability to climb trees. Flat Nose—that was his name—appeared on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, the exposure from which eventually led him to perform at the 1989 Super Bowl and star in a series of Japanese television commercials—a lot for a mutt from rural South Carolina.

Why was it so remarkable that this dog could climb trees? Maybe I’m biased—I once stepped outside as a child to find my dog on the roof—but it never seemed particularly strange to me. Many other species can do it skilfully—monkeys and leopards come to mind—without shocking anyone.

Have you ever seen a dog stare up at a squirrel in a tree and whine with impotence? Perhaps therein lies the issue.

@whataboutbunny

Silence of the Dogs

By the time I get home from work, the concept of even thinking in words exhausts me.

By Davis Dunham

1.11.2023

A dog rose to international fame in the 1980s for his ability to climb trees. Flat Nose—that was his name—appeared on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, the exposure from which eventually led him to perform at the 1989 Super Bowl and star in a series of Japanese television commercials—a lot for a mutt from rural South Carolina.

Why was it so remarkable that this dog could climb trees? Maybe I’m biased—I once stepped outside as a child to find my dog on the roof—but it never seemed particularly strange to me. Many other species can do it skilfully—monkeys and leopards come to mind—without shocking anyone.

Have you ever seen a dog stare up at a squirrel in a tree and whine with impotence? Perhaps therein lies the issue.

* * *

I don’t want to speak. More than that, I do not want to translate thoughts into words. We can feel thirst without defining what it is; as a child, you felt thirsty before you gained the ability to say so. Dogs, too—Flat Nose included—drink from water bowls, and they certainly don’t know the word “thirst.”

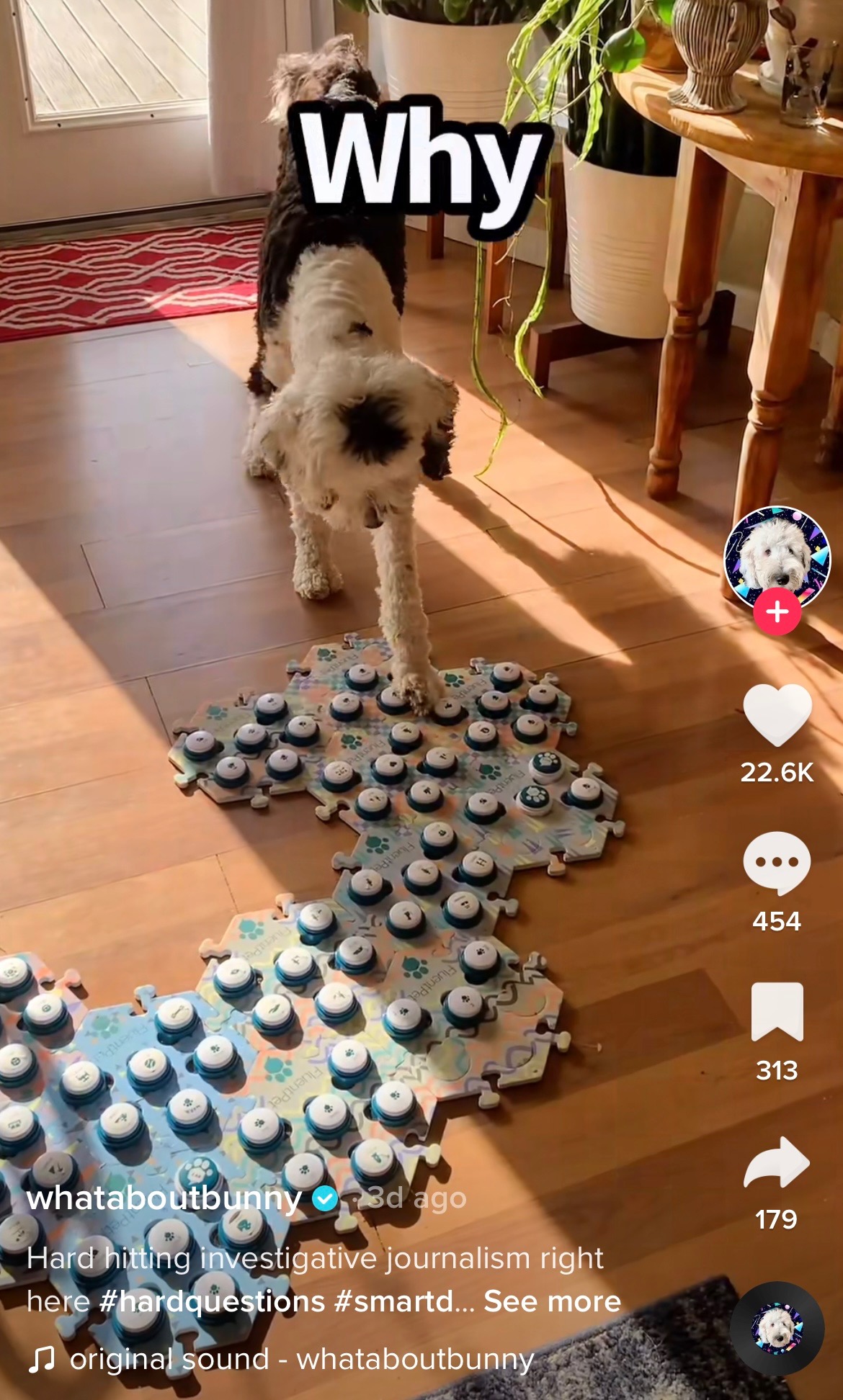

However, that might not be true. A dog named Bunny—username @whataboutbunny on TikTok—speaks with her owner regularly. Much like Flat Nose, she’s gained an atypical ability. She presses buttons with phrases loaded onto them with her paw, forming choppy sentences. “Mom. I love you. Mom. Help. Play,” she says in a video dated September 28. And, unlike most other dogs (a species not known for thoughtful patience), she then sits and waits as her mom brings her a toy and commences to play.

But does Bunny understand “play,” or is she simply a modern Pavlov’s dog? As I’ve gotten older, I’ve found myself increasingly tired with the idea that to understand something is to verbalize it. If you ask me, the word “verbalize” wouldn’t exist if what it describes happened naturally. Perhaps I find this idea so weary because of my work—I’m now an editor after studying English and creative writing. By the time I get home from work, the concept of even thinking in words exhausts me.

So, to help alleviate the stress, I’ve created a game for myself. Some evenings, usually after dinner, I smoke a joint, subsume into the couch, and see how long I can go without thinking a word. I think of it like the many science-fiction stories where the human mind eclipses its body: I descend into the pilling green chenille of my couch and find peace by reaching a level of consciousness that surpasses—or maybe skirts right underneath—verbalization.

Has Bunny found this peace? More so, has she lost it? I worry about this often, maybe because of what I have yet to mention: as I lay on the couch, playing my mental game, I let nature documentaries play in the background, and it is the animals’ wordlessness that makes the experience so peaceful. So, though it may be for personal reasons, I worry that we are corrupting Bunny.

* * *

In many ways, verbalization feels to me like cramming a square peg in a round hole. It gets the job done, but it can be a bit of a blunt instrument. You have to rely on a shared amount of understanding between all parties in order to have faith that what you really mean is what is being communicated. That’s why idioms rarely work across languages—a lack of shared context means non-English speakers (or even non-native English speakers) don’t quite understand what it means to “rain cats and dogs.”

For some, this bluntness is all that’s necessary. Bunny doesn’t need to specifically tell her mom that she would like to play with her squirrel toy—the one without the squeaker, please. Her and her mother, despite their many differences, have a strong understanding of each other. The mother likely knows what toys Bunny prefers and how to tell when she’s grabbed the right one, and this shared context makes the especially blunt verbiage of “Mom. Help. Play” effective. A wealth of shared idioms between the two, encompassing verbal and nonverbal cues, helps them understand each other.

But is it a dog’s responsibility to shoulder the weight of humanity’s idioms? Flat Nose didn’t need to understand much outside of a dog’s normal mindset in order to climb a tree, he just needed a strong enough desire to reach the top. But, if Bunny isn’t just expanding on Pavlov’s dog, she likely understands what “play” and “love” mean, and putting words in a creature’s head to define the bounds of a concept is innately corrupting. Delineating this as “play,” that as “mom”—yes, it does help Bunny communicate with her owner, but it also puts limits on what each of these concepts now mean to her. Bunny only needs her play button when she wants to play with someone—does her concept of “play” therefore only account for group activity? Does Bunny, in her own mind, keep a separate concept for the idea of solitary play? And, if dogs and humans have been able to communicate plenty well for millenia, is it worth it?

* * *

This has all been a lot of thinking, a lot of words—the latter of which is something I try to avoid. But maybe, as Bunny now knows, words are worth it when you have something you want to express. They might not perfectly, entirely, concisely sum up exactly what we want to say or think, but encompassing ideas in language makes them tangible, screws them to the sticking place. Bunny shows signs of this understanding when she waits patiently for her mom to come play—though language may be corrupting her, she is, at least in that moment, comforted by the knowledge that some form of her idea has gotten across.

In truth, verbalization is a skill—much like climbing a tree—and language is a tool, not the torture I sometimes see it for. Tonight, as I lay down on my worn couch, I hope Bunny too sinks into her bed—to sleep, perchance to dream, for hours without words.

@whataboutbunny