Original Art by Abby Millar

Patricia Lockwood’s No One Is Talking About This & the Cursèd Bird App

Lockwood’s superpowers, forged in her career as a poet and mutated by the nuclear waste of the internet, are on full display in her first novel.

By Philip kenner

9.20.2021

“What do you mean you've been spying on me, with this thing in my hand that is an eye?”

- Patricia Lockwood

It took a tiny act of God to get me off Twitter. On Halloween 2020, my phone fell into the bathroom sink, and enough water got inside to shut it down for good. I was able to replace my phone about a week later amid the exhausting, days-long 2020 election. Even when my phone was restored, I stayed off Twitter to avoid maddening election coverage. Once I avoided Twitter for two weeks, I began to fear what would happen if I returned. Would I approach Twitter with a new cautiousness, or would I redouble my habits? After all, I had been a daily visitor since I created my account in 2009. At the time of writing, I have yet to go back.

I can’t remember who came up with this, or if it brewed in my brain, but I started calling Twitter “The Cursèd Bird App.” I couldn’t break its addictive spell, despite the interface evoking a town square where everyone’s face was melting off. The algorithm and my primal following habits created a disturbing litany of men in their underwear, global tragedies, and pithy takes about romcoms. Every day, I would scroll and scroll until I felt my brain crust over like a cum sock. With Twitter, much like sour candy, tasting begets tasting. You don’t stop, even after your taste buds burn. One visit necessitates a second, and so on, until your cynicism and sense of humor elope, buy a house in your head, and flip it to sell for a profit. This habit-forming flavor of Twitter is the subject at the center of Patricia Lockwood’s first novel, No One Is Talking About This.

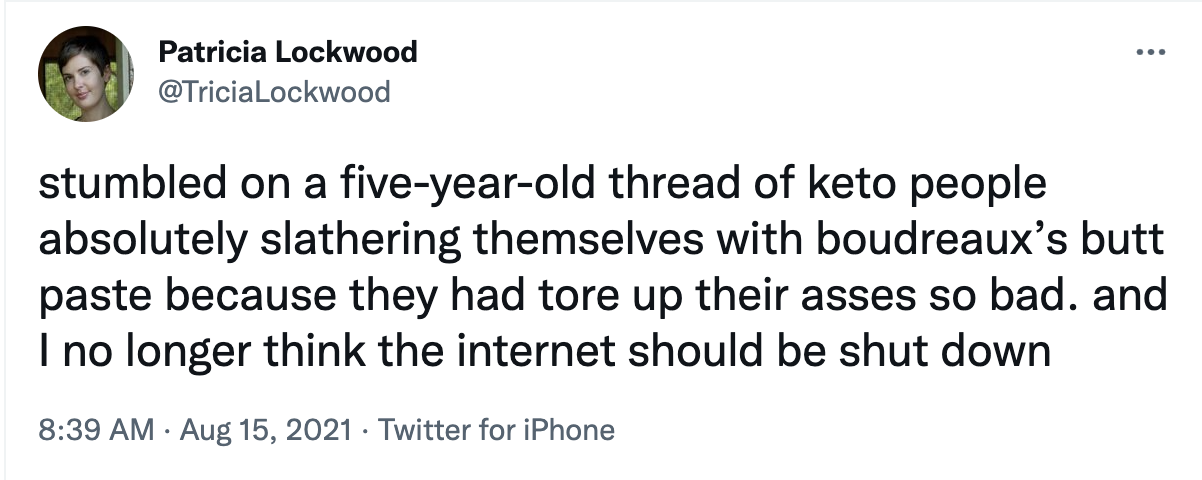

Patricia Lockwood joined Twitter in May 2011. She began her literary career as a poet, achieving virality with her poem “Rape Joke.” Her 2017 memoir, Priestdaddy, chronicles her experience moving back in with her father: a guitar-playing, often-shirtless, late-in-life Catholic priest. Priestdaddy launched Lockwood into literary rockstar status, but she was hitting sardonic home runs on Twitter for years prior. Lockwood’s prolific Twitter, where her bio reads, “hardcore berenstain bare-it-all,” built its audience from Lockwood’s ironic sexts. She often features her cats, Miette and Fenriz, the latter of whom she calls “Dr. Butthole.” Lockwood’s twitter features the same twisted lyricism as her books. Her writing savors irony and sarcasm while flaying itself into something vulnerable, like compressing an open wound with a tourniquet made from a Fruit by the Foot™. Lockwood draws the best and worst of Twitter into a panicked bird’s-eye view, and by doing so, we’re able to see the website more clearly.

In No One Is Talking About This, Lockwood’s superpowers, forged in her career as a poet and mutated by the nuclear waste of the internet, are on full display. The novel opens on an unnamed woman who has achieved a significant following online because of her dry, irreverent posts. Our internet-addled protagonist travels the world, speaking to the public about memes and internet culture. The first half of the novel reads much like Twitter: little paragraphs of provocative shrapnel exploring larger themes of alienation, dissociation, and being “very online.” Not only is No One Talking About This disturbing, revealing, and emblematic of the endless scroll, but it’s hilarious. I mean, like, guffawing-on-the-train hilarious. Lockwood’s embrace of bleak comedy is no accident; Twitter’s greatest trick is forcing an acid-mouth chuckle amidst global and interpersonal tragedies. How can I be laughing so hard at a Shrek meme after seeing a GoFundMe for someone’s chemotherapy?

In the second half of the book, Lockwood’s protagonist undergoes a massive change in perspective. Without spoiling the plot, the social media-obsessed narrator must adapt to new rhythms, deeper thoughts, and the unpredictable weather of the human body. The narration slows. We stay with characters for longer. The sarcasm begins to wilt. Subsequently, Twitter takes a backseat. The narrator loses interest in “The Portal,” Lockwood’s euphemistic name for all things social media. The online world reveals itself to be what it always was: ephemera.

But, actually, wait. “Ephemera” isn’t the right word. The online world is far from ephemera. It’s real. So real, in fact, that it has become the battleground for every culture war and the last two presidential elections. Its enormity stretches before us, so much so that our little rat brains have yet to grasp its ability to fuck with us. I had a coworker in electoral organizing who tried to assuage our team’s fears about an online conflict by saying, in a tone most soothing, “Twitter isn’t real life.” That calmed me then, but I don’t agree anymore.

I admit, it’s just a bundle of stupid pixels on our tiny, evil screens, but isn’t social media still real people, saying real things with real consequences? I often go in circles about social media, as evidenced by this essay. Is social media a true hellscape, or is it not as malevolent as it seems, like a monster under the bed? This very struggle haunts Lockwood’s protagonist as she comes to terms with a life-changing event and relegates “The Portal” to a lower spot on the priority list. Her urge to escape into The Portal turns to a lower volume. It seems to me, however, that once you leave the online world, whether it’s for six minutes or six months, the craving to return will find you. What if there’s something you’re missing? What if, this time, your feed will just be jokes and edifying memes? What if all the violence and tragedies are over? How will you know if you don’t check? And then check? And then check again? We promise it’s not scary anymore. Come back. Please.

Then, there’s the ghost of good intentions. We joined these sites to connect with loved ones and gush over photos of our crush at summer camp, but an errant wind steered our ships someplace darker. We now take for granted that the myriad textures of the internet—even the most mundane websites—are spiky with conspiracy theories, death threats, and unthinkable hatred. Lockwood writes: “Previously these communities were imposed on us, along with their mental weather. Now we chose them—or believed that we did. A person might join a site to look at pictures of her nephew and five years later believe in a flat earth.”

We all have our own version of “looking at pictures of her nephew” and “believing in a flat earth.” What did we come here for, and what are we leaving with instead? For example, I walked into Tumblr around 2008 to engage with Glee content, and I walked out in 2018 with a list of favorite porn accounts. Of course, creating a porn charcuterie board and becoming a flat earther are two worlds apart, but the point stands. There’s no such thing as coming away unchanged. We arrive at the websites to broadcast ourselves as we are in that moment (à la Facebook’s “What’s on your mind?”), but instead, we end up performing our mutations. Together and in front of our loved ones, we burgeon into panicked digital adulthoods, like a B’nei Mitzvah ceremony where everyone is on speed.

Lockwood digests this phenomenon in No One Is Talking About This: “The people who lived in the portal were often compared to those legendary experiment rats who kept hitting a button over and over to get a pellet. But at least the rats were getting a pellet, or the hope of a pellet, or the memory of a pellet. When we hit the button, all we were getting was to be more of a rat.” In the wake of the Ratatouille TikTok musical, who wouldn’t want to become more of a rat? We’re careening deliberately toward rat consciousness, bragging about our thick pink tails, hoping that someone retweets with, “That’s it. That’s the tweet.”

In an attempt to represent the tone and pace of Twitter, No One Is Talking About This presents a smorgasbord of references, some of which are indecipherable. I concede that at times, the book reads like one long inside joke. Roxane Gay, in her Goodreads review, writes, “It does feel like two novels in one. The first is a novel about what it means to be Very Online and if you aren’t, I am not sure that it will make sense.” While I share Gay’s concern, I ultimately enjoyed getting lost in the sauce. Many jokes went over my head, proving that it’s difficult to grasp the platform’s enormity, even when you spend over two hours a day on the app for eleven years. While Lockwood’s density of references was destabilizing at first, I came out the other side grateful for the delightful confusion. Lockwood successfully defamiliarized an online culture to which I previously claimed membership.

This very online culture, whether it’s bred by Twitter or its siblings, reflects us back to ourselves like a funhouse mirror. Put differently, I know I’m looking at myself, but something is off. A quirk has been augmented. We believe, by depositing our witty takes and earnest celebrations, that we’re changing the internet, but in truth, it changes us. We are the passive voice behind the algorithms. Lockwood pushes against those of us experiencing Main Character Syndrome: “It was a mistake to believe that other people were not living as deeply as you were. Besides, you were not even living that deeply.”

In No One Is Talking About This, Lockwood borrows the manic fabric of Twitter in an attempt to make a quilt, and she succeeds with distressing precision. Reading the novel made me feel like I had logged in after many months away. On the day I’m writing this sentence, No One Is Talking About This has earned its spot on The Booker Prize shortlist, and theologian Dr. Rowan Williams, in his entry on the novel, writes, “Patricia Lockwood manages to tell her story in the glancing, mayfly-attention-span idiom of contemporary social media, but she uses this apparently depth-free dialect with precision and even beauty.” Although Williams hits the nail on the head with “mayfly-attention-span,” his use of the phrase “depth-free dialect” rings untrue to me, given that social media is exhausting precisely because everything is laden with depth. Every day, people’s most traumatic stories float in front of our eyes. Desperate pleas for political action are constant. Just tapping through Instagram stories requires you to do one of two things: devolve into a genuine puddle of tears or completely turn off the part of your brain that feels empathy. Even thirst traps have Didion-esque confessionals slathered below them. There’s more meaning to a well-photographed nipple when it can speak for itself. Don’t tell me what your nipple means! Let me find the meaning in your nipple! Trust your audience!

I digress. No One Is Talking About This, even in its title, rolls around in the poppy field of irony. Everyone is talking about everything all the time, rendering the question “Why is no one talking about this?” the ultimate cringe. It brings to mind a white person suddenly galvanized by their discovery of a previously long-existing injustice. In Dave Malloy’s Octet, the sopranos and altos come together for a tinny jab at self-congratulatory social media users: “Yesterday, I heard someone somewhere did something somewhat awful. Are you outraged? Are you outraged?” This reminds me of KONY 2012. Remember that? Of course you do. We’re still making memes about it. It was humiliating to get caught up in that sharknado of internet performance. Social media is a place where we come to throw rotten tomatoes at the stage, only to realize that we were actually on the stage ourselves, or maybe we were the tomato, or maybe the whole audience was a simulation, or maybe tomatoes are canceled, or maybe cancellations are canceled, or maybe look at this meme about how Grimes named her kid “C-3P0” or whatever.

Patricia Lockwood has tapped into this shitstorm and reflected it in a superlative novel. While it may defer to a “Very Online” audience, that audience is ever-expanding (for reference, between 2019 and 2020, Twitter received approximately 47 million new users). No One Is Talking About This opens itself in shards, arranged in sequence like a cartoon to-do list, unspooling itself on the ground. Lockwood is a magician of meaning and terror and the terror of meaning. It would be inaccurate to say the book meets the moment; it is, in a clownish dance, attempting to present the moment, however impossible it is to catch. With 500 million new tweets per day, representing Twitter in a novel is a futile mission. Thankfully, Lockwood embraces the futility, chews it up, and spits it back out. We are lucky to be the baby bird on the receiving end.

Special thanks to Leah Parker-Bernstein and Georgia Petersen for their feedback.

- Patricia Lockwood

It took a tiny act of God to get me off Twitter. On Halloween 2020, my phone fell into the bathroom sink, and enough water got inside to shut it down for good. I was able to replace my phone about a week later amid the exhausting, days-long 2020 election. Even when my phone was restored, I stayed off Twitter to avoid maddening election coverage. Once I avoided Twitter for two weeks, I began to fear what would happen if I returned. Would I approach Twitter with a new cautiousness, or would I redouble my habits? After all, I had been a daily visitor since I created my account in 2009. At the time of writing, I have yet to go back.

I can’t remember who came up with this, or if it brewed in my brain, but I started calling Twitter “The Cursèd Bird App.” I couldn’t break its addictive spell, despite the interface evoking a town square where everyone’s face was melting off. The algorithm and my primal following habits created a disturbing litany of men in their underwear, global tragedies, and pithy takes about romcoms. Every day, I would scroll and scroll until I felt my brain crust over like a cum sock. With Twitter, much like sour candy, tasting begets tasting. You don’t stop, even after your taste buds burn. One visit necessitates a second, and so on, until your cynicism and sense of humor elope, buy a house in your head, and flip it to sell for a profit. This habit-forming flavor of Twitter is the subject at the center of Patricia Lockwood’s first novel, No One Is Talking About This.

Patricia Lockwood joined Twitter in May 2011. She began her literary career as a poet, achieving virality with her poem “Rape Joke.” Her 2017 memoir, Priestdaddy, chronicles her experience moving back in with her father: a guitar-playing, often-shirtless, late-in-life Catholic priest. Priestdaddy launched Lockwood into literary rockstar status, but she was hitting sardonic home runs on Twitter for years prior. Lockwood’s prolific Twitter, where her bio reads, “hardcore berenstain bare-it-all,” built its audience from Lockwood’s ironic sexts. She often features her cats, Miette and Fenriz, the latter of whom she calls “Dr. Butthole.” Lockwood’s twitter features the same twisted lyricism as her books. Her writing savors irony and sarcasm while flaying itself into something vulnerable, like compressing an open wound with a tourniquet made from a Fruit by the Foot™. Lockwood draws the best and worst of Twitter into a panicked bird’s-eye view, and by doing so, we’re able to see the website more clearly.

In No One Is Talking About This, Lockwood’s superpowers, forged in her career as a poet and mutated by the nuclear waste of the internet, are on full display. The novel opens on an unnamed woman who has achieved a significant following online because of her dry, irreverent posts. Our internet-addled protagonist travels the world, speaking to the public about memes and internet culture. The first half of the novel reads much like Twitter: little paragraphs of provocative shrapnel exploring larger themes of alienation, dissociation, and being “very online.” Not only is No One Talking About This disturbing, revealing, and emblematic of the endless scroll, but it’s hilarious. I mean, like, guffawing-on-the-train hilarious. Lockwood’s embrace of bleak comedy is no accident; Twitter’s greatest trick is forcing an acid-mouth chuckle amidst global and interpersonal tragedies. How can I be laughing so hard at a Shrek meme after seeing a GoFundMe for someone’s chemotherapy?

In the second half of the book, Lockwood’s protagonist undergoes a massive change in perspective. Without spoiling the plot, the social media-obsessed narrator must adapt to new rhythms, deeper thoughts, and the unpredictable weather of the human body. The narration slows. We stay with characters for longer. The sarcasm begins to wilt. Subsequently, Twitter takes a backseat. The narrator loses interest in “The Portal,” Lockwood’s euphemistic name for all things social media. The online world reveals itself to be what it always was: ephemera.

But, actually, wait. “Ephemera” isn’t the right word. The online world is far from ephemera. It’s real. So real, in fact, that it has become the battleground for every culture war and the last two presidential elections. Its enormity stretches before us, so much so that our little rat brains have yet to grasp its ability to fuck with us. I had a coworker in electoral organizing who tried to assuage our team’s fears about an online conflict by saying, in a tone most soothing, “Twitter isn’t real life.” That calmed me then, but I don’t agree anymore.

I admit, it’s just a bundle of stupid pixels on our tiny, evil screens, but isn’t social media still real people, saying real things with real consequences? I often go in circles about social media, as evidenced by this essay. Is social media a true hellscape, or is it not as malevolent as it seems, like a monster under the bed? This very struggle haunts Lockwood’s protagonist as she comes to terms with a life-changing event and relegates “The Portal” to a lower spot on the priority list. Her urge to escape into The Portal turns to a lower volume. It seems to me, however, that once you leave the online world, whether it’s for six minutes or six months, the craving to return will find you. What if there’s something you’re missing? What if, this time, your feed will just be jokes and edifying memes? What if all the violence and tragedies are over? How will you know if you don’t check? And then check? And then check again? We promise it’s not scary anymore. Come back. Please.

Then, there’s the ghost of good intentions. We joined these sites to connect with loved ones and gush over photos of our crush at summer camp, but an errant wind steered our ships someplace darker. We now take for granted that the myriad textures of the internet—even the most mundane websites—are spiky with conspiracy theories, death threats, and unthinkable hatred. Lockwood writes: “Previously these communities were imposed on us, along with their mental weather. Now we chose them—or believed that we did. A person might join a site to look at pictures of her nephew and five years later believe in a flat earth.”

We all have our own version of “looking at pictures of her nephew” and “believing in a flat earth.” What did we come here for, and what are we leaving with instead? For example, I walked into Tumblr around 2008 to engage with Glee content, and I walked out in 2018 with a list of favorite porn accounts. Of course, creating a porn charcuterie board and becoming a flat earther are two worlds apart, but the point stands. There’s no such thing as coming away unchanged. We arrive at the websites to broadcast ourselves as we are in that moment (à la Facebook’s “What’s on your mind?”), but instead, we end up performing our mutations. Together and in front of our loved ones, we burgeon into panicked digital adulthoods, like a B’nei Mitzvah ceremony where everyone is on speed.

Lockwood digests this phenomenon in No One Is Talking About This: “The people who lived in the portal were often compared to those legendary experiment rats who kept hitting a button over and over to get a pellet. But at least the rats were getting a pellet, or the hope of a pellet, or the memory of a pellet. When we hit the button, all we were getting was to be more of a rat.” In the wake of the Ratatouille TikTok musical, who wouldn’t want to become more of a rat? We’re careening deliberately toward rat consciousness, bragging about our thick pink tails, hoping that someone retweets with, “That’s it. That’s the tweet.”

In an attempt to represent the tone and pace of Twitter, No One Is Talking About This presents a smorgasbord of references, some of which are indecipherable. I concede that at times, the book reads like one long inside joke. Roxane Gay, in her Goodreads review, writes, “It does feel like two novels in one. The first is a novel about what it means to be Very Online and if you aren’t, I am not sure that it will make sense.” While I share Gay’s concern, I ultimately enjoyed getting lost in the sauce. Many jokes went over my head, proving that it’s difficult to grasp the platform’s enormity, even when you spend over two hours a day on the app for eleven years. While Lockwood’s density of references was destabilizing at first, I came out the other side grateful for the delightful confusion. Lockwood successfully defamiliarized an online culture to which I previously claimed membership.

This very online culture, whether it’s bred by Twitter or its siblings, reflects us back to ourselves like a funhouse mirror. Put differently, I know I’m looking at myself, but something is off. A quirk has been augmented. We believe, by depositing our witty takes and earnest celebrations, that we’re changing the internet, but in truth, it changes us. We are the passive voice behind the algorithms. Lockwood pushes against those of us experiencing Main Character Syndrome: “It was a mistake to believe that other people were not living as deeply as you were. Besides, you were not even living that deeply.”

In No One Is Talking About This, Lockwood borrows the manic fabric of Twitter in an attempt to make a quilt, and she succeeds with distressing precision. Reading the novel made me feel like I had logged in after many months away. On the day I’m writing this sentence, No One Is Talking About This has earned its spot on The Booker Prize shortlist, and theologian Dr. Rowan Williams, in his entry on the novel, writes, “Patricia Lockwood manages to tell her story in the glancing, mayfly-attention-span idiom of contemporary social media, but she uses this apparently depth-free dialect with precision and even beauty.” Although Williams hits the nail on the head with “mayfly-attention-span,” his use of the phrase “depth-free dialect” rings untrue to me, given that social media is exhausting precisely because everything is laden with depth. Every day, people’s most traumatic stories float in front of our eyes. Desperate pleas for political action are constant. Just tapping through Instagram stories requires you to do one of two things: devolve into a genuine puddle of tears or completely turn off the part of your brain that feels empathy. Even thirst traps have Didion-esque confessionals slathered below them. There’s more meaning to a well-photographed nipple when it can speak for itself. Don’t tell me what your nipple means! Let me find the meaning in your nipple! Trust your audience!

I digress. No One Is Talking About This, even in its title, rolls around in the poppy field of irony. Everyone is talking about everything all the time, rendering the question “Why is no one talking about this?” the ultimate cringe. It brings to mind a white person suddenly galvanized by their discovery of a previously long-existing injustice. In Dave Malloy’s Octet, the sopranos and altos come together for a tinny jab at self-congratulatory social media users: “Yesterday, I heard someone somewhere did something somewhat awful. Are you outraged? Are you outraged?” This reminds me of KONY 2012. Remember that? Of course you do. We’re still making memes about it. It was humiliating to get caught up in that sharknado of internet performance. Social media is a place where we come to throw rotten tomatoes at the stage, only to realize that we were actually on the stage ourselves, or maybe we were the tomato, or maybe the whole audience was a simulation, or maybe tomatoes are canceled, or maybe cancellations are canceled, or maybe look at this meme about how Grimes named her kid “C-3P0” or whatever.

Patricia Lockwood has tapped into this shitstorm and reflected it in a superlative novel. While it may defer to a “Very Online” audience, that audience is ever-expanding (for reference, between 2019 and 2020, Twitter received approximately 47 million new users). No One Is Talking About This opens itself in shards, arranged in sequence like a cartoon to-do list, unspooling itself on the ground. Lockwood is a magician of meaning and terror and the terror of meaning. It would be inaccurate to say the book meets the moment; it is, in a clownish dance, attempting to present the moment, however impossible it is to catch. With 500 million new tweets per day, representing Twitter in a novel is a futile mission. Thankfully, Lockwood embraces the futility, chews it up, and spits it back out. We are lucky to be the baby bird on the receiving end.

Special thanks to Leah Parker-Bernstein and Georgia Petersen for their feedback.