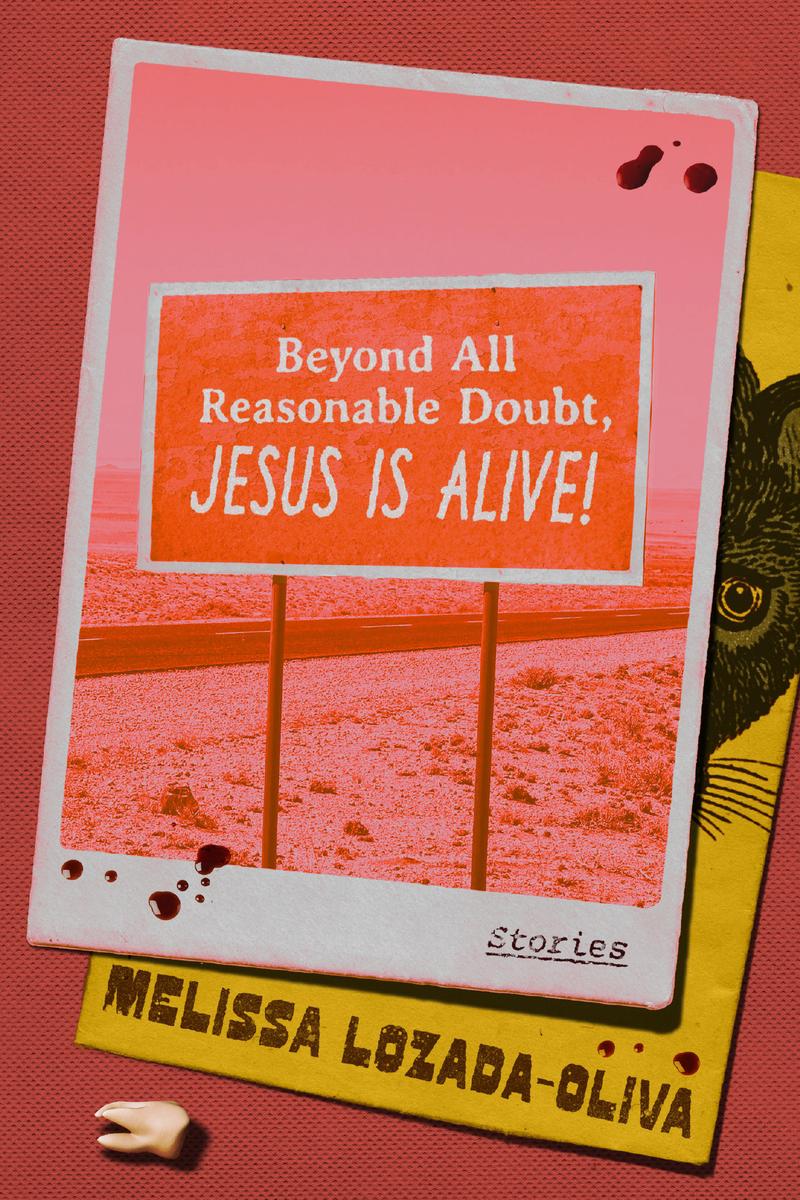

Cover art by Luísa Dias.

Salvation in All the Wrong Places

Talking faith and fear with Melissa Lozada-Oliva, author of Beyond All Reasonable Doubt, Jesus is Alive!

By Taylor Stout

9.4.2025

On my weekly walks from the Smith-9th Street subway station to the Red Hook waterfront, as I passed under the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, a billboard above a kitchen design store always caught my eye in the fading light. It read:

“Losing FAITH in GOD?

Call (83) FOR-TRUTH.”

Call (83) FOR-TRUTH.”

There was something enrapturing in its extremity: the idea that truth was only a phone call away, that my reckoning with faith could be resolved simply by dialing a string of numbers into the object I hold perpetually in my hand, the same object that often serves to aggravate this very reckoning.

I’d pass this billboard on my way to a writing workshop organized by the Brooklyn Public Library and led by Melissa Lozada-Oliva, author of the chapbook peluda, the novel-in-verse Dreaming of You, and the novel Candelaria. Lozada-Oliva’s new short story collection, Beyond All Reasonable Doubt, Jesus Is Alive!, out September 2 from Astra House, transported me back to those fall evenings and the devout billboard that lingered in my mind through them all. With a masterful blending of horror and humor, Lozada-Oliva depicts women facing trials both surreal and mundane. All are desperate for something to believe in. I spoke with Lozada-Oliva to learn more about her inspirations for this collection, her thoughts on the horror genre, and the importance of community to her creative practice.

Photo by Taylor Stout.

*This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

COPY: You have a new collection of stories called Beyond All Reasonable Doubt, Jesus Is Alive!—an amazing title, so I wanted to start by asking you about it. I imagine it's found text on a billboard or something, one of those kind of crazy religious ones you see on the side of the highway. What drew you to these words, and how do they speak to the stories?

MELISSA LOZADA-OLIVA: So the true phrase on the billboards is, “Beyond reasonable doubt, Jesus is alive!” I added the “all,” perhaps for legal reasons and also because I just remembered it that way. Those proclamations on billboards are just so insane and kind of beautiful syntactically—love the comma, love the exclamation point. I just love this deep, wild belief in huge letters. The phrase was just stuck in my head while I was writing this book, and I think what this book is mostly about is women trying to find salvation in all the wrong places. The title story is about this girl who takes this strange road trip with her former teacher, who is a bad man. She points out the billboard, and they're kind of trying to be cheeky and funny about it, trying to be above this huge, insane proclamation, without realizing that she's also doing something insane and also is in desperate need of something to believe in. All of the stories border between, “Is this real?” and, “Is this not real?” It's up to the reader and also up to us as people to figure out: what's going to be our compass through life?

It's interesting that you say it was stuck in your head. Did you conceive of this collection as a way to explore that theme, or was it more that you found these themes emerging repeatedly in your work?

I feel like the title came later, after a lot of the stories were done. Even now, looking through it, I'm like, “Yeah, this is what's going on here.” A lot of people have been noticing how much body horror is in it, and I kind of didn't pick up on that at all. That just kept coming up. There's this theme of protection and bad energy throughout the book.

As you mention, it balances these horror elements with the question of what's real and what's not. What are some of your earlier, formative experiences with horror media, and what drew you to this genre to work in?

I feel like working in the horror, spectral space is somewhat recent. Dreaming of You, my first book, which is about a poet who brings Selena back to life, was my first exploration in that. Then, I realized that I really liked that space. Before, I was kind of just writing about identity, but actually, I always was writing about zombies. But I felt like I was too, I don't know, “literary” for it. Actually, I found that it really helps you explore complicated feelings.

I am an averagely aged Millennial, which means my experience with media is unique because I remember a world without the internet. I also remember this space between; I witnessed rapidly moving technology. As a kid, if I wanted to go on the internet, I had to wait for dial-up, and there was this horrible noise that would be the internet dialing up, and then all of a sudden, I was logged on, but it blocked anybody from being able to call the house. It was the space of waiting that was a little uncanny. I would watch these three videos that were saved on our computer that were just trailers for movies. I would watch them over and over again because that was all there was to do. There was so much boredom. I loved the show So Weird as a kid. It was like The X-Files for kids. It was about this girl Fiona and her rockstar mom, and they were always on the road, and she encountered freaky things on the road that didn't have any explanation. It aired from 1999 to 2001. I just loved the show. I watched an episode recently and had this very I Saw the TV Glow experience of being like, “This is not what I thought it was.”

Reading your collection reminded me a lot of the writing workshop I took with you. One of the stories in particular [“Heads”] made me think about a prompt you gave us, which was to write about yourself at thirteen encountering something or someone dangerous, but you're the only one who sees the danger. I was thinking about that in this collection because there's moments where we're not sure what's happening, and also, most of the protagonists of the stories are young women or even teenagers. What are the particularities of horror written by and for women and girls?

In order to be safe as women and girls, we're taught to be afraid. We're given really intense warnings and instructions about how to go about our lives, who to not speak to, how to get home, who to trust, who not to trust. Inside of every woman and girl, there is a deep fear that other people don't understand. Also, I'm saying this as a cis woman, and I think to be a trans person, walking home alone at night, is a fear that I don't understand. I won't ever fully know. I see amazing spectral fiction from trans writers—for example, this book called Cuckoo [by Gretchen Felker-Martin], and I Saw the TV Glow [written and directed by Jane Schoenbrun] as we were talking about. I think people who experience their body being in danger every day have a really unique experience to horror.

A lot of coming of age is understanding what is truly dangerous and what is not. You're not given a lot of context for things, and you're not given context out of safety. You're not told the whole truth because people want to protect you from what has happened, what could happen to you. When you're a thirteen-year-old and you're seeing something dangerous, and no one wants to talk about it, that's a very unique experience.

It strikes me because I feel like the horror genre is such a male-dominated thing, and women are obviously in it, but as these pawns. And yet reading it or absorbing it, it speaks so much to my experience as a girl or another marginalized experience, like you say. So it's really thrilling to read something like this, that feels like it's using it as a metaphor and playing into that.

The other recurring motif is these religious imageries and the idea of faith. Both use mystery really well in the withholding of information—that's the space where either fear or faith can come in and make a whole story come alive. I'm wondering if you could talk a little bit more about how horror and religion are connected in your mind.

Oh my God. Yeah, totally. I think they're both used as moral fables. I grew up Catholic, and so a lot of my understanding of how to be a good person in the world comes from Catholicism and the teachings of Jesus. I would pray every night as a kid. I like, loved God as a kid. We moved school districts, so I moved from a Catholic school to a public school, and I was really upset that there was no God in the curriculum. And then, my parents got divorced, and I discovered rock and roll. And I was like, “Oh my God, who needs God?” But I also think there's so much blood in religion, and there's so much sacrifice, and the Bible's really scary. I don’t know if you've ever seen that there's that angel who has like, a billion eyes?

Yep, I grew up Catholic as well.

Yes! A lot of the Gothic is just Catholic. It's strange to reclaim. I want to feel faithful in some way, and I think I always maybe will be, but it's hard. It's such a freaky religion, the imagery and iconography. There's that scene [in Beyond All Reasonable Doubt, Jesus Is Alive!] where someone visits the Cristo Negro, and she sees Jesus and she's like, “This looks like Lady Gaga.” There's a lot of camp to it.

That’s one thing—despite the qualms I have with Catholicism, I love the drama and the gaudy aesthetic. The blood, the tears. It's wonderful.

Speaking to that sense of urgency, you mentioned earlier that these protagonists are all people who are desperately searching for salvation or something to believe in. One of my favorite stories was “Tails,” and the opening line of that is, “I never thought I'd have to make the choice, but you're never prepared until you have to be.” What draws you as a writer to these moments of urgency and to guiding your characters through them?

“Tails” is my favorite story. I had so much fun. I wrote it locked inside my house in the pandemic, and I wanted to make myself laugh. But there’s still horror in that.

A lot of fiction is inventing little people you're torturing. I don't want to torture them, I want them to go through something and I want them to be okay, but they're not full people unless they've gone through something. In life, I feel really frozen with decision, so I want to explore that with characters. With “Tails,” she doesn't really make a decision. It's just given to her. Sometimes in life, you get sick and there's nothing you can do, or someone you love dies and there's nothing you can do. Or you have a whole life happening, and then an accident happens. That is very evident in the “Tails” journey where she's just like, “I didn't ask for this, but all of a sudden I inherited it, and I have to fucking deal with it.”

Shifting gears a little, I want to talk about our workshop, teaching, and creative spaces. I mentioned I took a workshop with you through the Brooklyn Public Library, and what I really loved about that space was that it was a low-pressure creative community, but at the same time, everyone was dedicated and bringing their own different work to it. What role does community play in your writing and your creative practices?

I started doing slam poetry, and so my understanding of writing has a lot to do with audience and reaction and feedback, or hearing what people think about my writing. When I stopped doing that, I was in a workshop. So I feel like my work is always like, I can't do it unless I know someone else is going to read it.

At the same time, my work only gets better when I'm an active reader and an active audience member. I'm always reading things that my friends are writing. I'm in a workshop myself. It’s three other writers. We all meet every Monday. We exchange stuff, and it's really low-pressure, but we need this accountability system, and it's also so helpful to write knowing who the eyes are going to be. Sometimes, when I want to give myself a deadline, I text someone, “Can I send you something?” so I can see it as though they're reading it. Another thing that has been so crucial to me writing is teaching these workshops. I've taught so much in the last two years with the Red Hook Library, with the Center for Fiction, and now Columbia. I've taught classes online myself, and it's a good reminder of how much other people need this too.

With your class, it was really beautiful to see all of you bond over your writing, and you were all strangers too. To see all of the generosity that you all brought with each other every week, and this need to impress one another, it was really cool, and also to have a hand in what you guys are writing by giving you these readings. The discussions that happened there fuel my writing too. That has been a really important part of my life as a writer. And I know that you guys all meet together.

Yeah, we do, which feels so magical because we were just a group of strangers, and I remember registering for that workshop on a whim and just being like, “Whatever, it's free. We'll see what happens.” And the fact that I have these supportive, lasting bonds with these people I wouldn't have met otherwise is awesome.

That's so beautiful. Yeah.

It’s great to have people who are coming from different backgrounds, but we're bonding over this shared creative tool. Going off of that, the workshop was free—shoutout public library funding—and as an artist in New York, this city is so often viewed as a mecca of hypercapitalism. I'm curious to hear about how you work to cultivate these spaces that allow you to make time for creative practice, and your thoughts on balancing survival with your art.

I know. It is literally every day. What do you choose to do? It's very hard. I feel really lucky to be able to support myself. I also know I wouldn't be able to do it without my partner or the community that I have around me. Maybe again this is like something to do with slam poetry, but I'm always at readings. I'm always talking to people, and I met my agent by going to a party. I'm a really social person, which is really beneficial and a good way to live in New York. But that also means that in order to water yourself, you have to water your friendships and the artistic communities around you.

I'm a child of immigrants, and I’m really scrappy. So I was like, “I need a job.” For five years, I was supporting myself by doing university visits that paid me a bunch of money. Dude, I was fucking living, and my rent was really cheap at the time, and I was getting flown out. Then, the economy tanked, and nobody has invited me to do that in a while. I don't know people who do that anymore. It was this moment in time where I was able to live that way. So I was like, “What do I do now?” I can teach and I can do service. For about a year and a half, I worked at the Center for Fiction in their cafe, serving coffee. There, I met a lot of writers and started teaching a class, and now that's part of my community too. I teach classes online. I have a Substack. My mom and dad are small business owners and immigrants, and they're just like, “You can do it.” I have that energy to do this on my own.

However, it would be great if I didn't have to kill myself. I think it should be a right to make art and not this backbreaking privilege. There should be grants at disposal. I'm so grateful for the Brooklyn Public Library because they gave me this gig. At the same time, I wish there was more of that. New York City's an amazing place to be a writer. It would be amazing if housing was cheaper, and I think because of that, I also got really involved in the Zohran campaign, with Anna [from workshop].

Yeah, she mentioned. I love that. That shows the real grassroots movement of it, y'all running into each other.

I know. It was really beautiful. But yeah, I think if you're an artist in New York City, you have to be involved in New York City politically. Because we all want to be able to afford to live here.

Order a copy of Beyond All Reasonable Doubt, Jesus Is Alive! from an independent New York City bookstore here.