The Brief And Wondrous Life of the Metrocard

The swan song of a new york city icon.

By JoliAmour DuBose-Morris

11.21.2025

My death is somewhere between a murder, an assisted suicide, and your birth. On December 31, I imagine that all of the people who made me—the cats over at Cubic Transportation Systems, everyone both dead and alive—will stand around my bed and say their goodbyes or early ‘cakes and candles.’ I’ve only been around for 31 years. They’ll kill me in a couple of ways. By sunlight, they’ll reduce me down to gradient microplastics, which could possibly add time to that Union Square ‘Earth-Dead’ countdown. This, I don’t know for sure, but I can’t rule it out. If not sunlight or weathering, then I’m sure there are other ways to do me in. One of them being the rise of you.

You never knew much about me. We never really ran in the same circles, your friends not really my friends, your passengers not really my passengers—most of them never even purchased me once they transplanted. I’d been the memento to have from a winter visit, a Midwest family cupping me in a gloved hand while marvelling the lit trees of Rockefeller. Or at the end of August, when I’d been taped to a scrapbook to go with all the summer memories of a socialite, her wanting to remember the time she did an arts residency and almost married (which really means almost dated which really means almost went on a third date with) some guy she met at an LES networking gallery thing-a-majig.

I thought there could be enough space for both of us, but my existence ceases here to elongate your progression. I can’t say I’m unfamiliar with the feeling, ‘once a cheater, always a cheater.’ The MTA’s an advancer, New York is all about its new.

Before me, because I know you don’t read, the MTA used to be a coin-based system. Like nickels, and such. There was just a slot, and a nickel pushed through to ride a five-cent train. In ‘43, our bosses or fathers or deities traded in the nickel for dimes. Ten years later, they added another five cents to make fifteen. And a fifteen coin was made—not by the government, but by the MTA’s first token machine, because obviously there was no fifteen-cent coin and like, yeah. I don’t have to explain inflation to you, or capitalism, I’m sure you get the gist, the price just kept rising. But then it wasn’t really about the price anymore, more so that the powers that be wanted a computerized system which gave them access to where everyone was all at once. One unique and ten-digit serial number later, I was born out of the blues and yellows which conjure surveillance.

But at least I thought I was also made out of love. And the coins, after a while, they just weren’t usable. That’s what I told myself, and in extrapolation, I imagine you mull the same noise.

By ‘94, during Quentin Tarantino’s ascent into Hollywood, Nelson Mandela’s officiation into presidency, and the year Kurt Cobain died, my existence was announced on WABC 7 by blonde-bobbed anchor Diana Williams. Everyone commuted to Whitehall Station to see me and bend me ‘round, most of them wondering how their paper dollars somehow lived inside of me. I’d been a technological miracle. The Big Apple’s secondborn, and by 2003, I’d outlived my eldest sibling, the tokens reduced to passed remembrances about the “back whens” in bodegas. Someone’s grandmother berating her teenage grandson about his ingratitude for a five-dollar allowance: “You know, back in my day, we could survive off a whole lot of nothing. Just a couple of cents needed for a sweet.”

And the grandson would suck his teeth, waving his grandmother off, and jumping on the J with me in his coat pocket. His mouth mumbling to Nas lyrics at Myrtle Broadway.

Even though the token machines were discontinued, I do pride myself on how much the coins and I interacted even after. We were always in dialogue. I knew little girls who hunted for change in their sofas and the jars of pennies sitting in the linen closet so they at least had the $1.50 needed to board on the Q17 to grab a one-transfer. I’m a philanthropist, if you will.

I’d been a helper to senior citizens, to the firemen, to the students; to the ninth graders plucking at my plastic as they sludged their backpacks over their shoulders, heading to grab a dollar slice before putting me to use.

When they made you, did they consider all of these factors? OMNY, the tap-and-go card to make transportation simpler. I understand what technology can do, I am a product of it. I understand that we possess airtrains, and robodogs, and social media apps (some for taking pictures or exposing a cheating scandal), but where’s the intersectionality? OMNY, the tap-and-go card with a solid, matte black color. OMNY, the million-in-one, the three-by-two tap-dancing technology advancement to remove everything New York stands for. Something about your existence troubles me to question if the end of the world is Google Maps-able. I might’ve been used for transportation, but I was also the timestamp of culture.

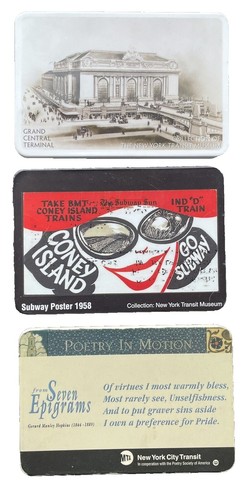

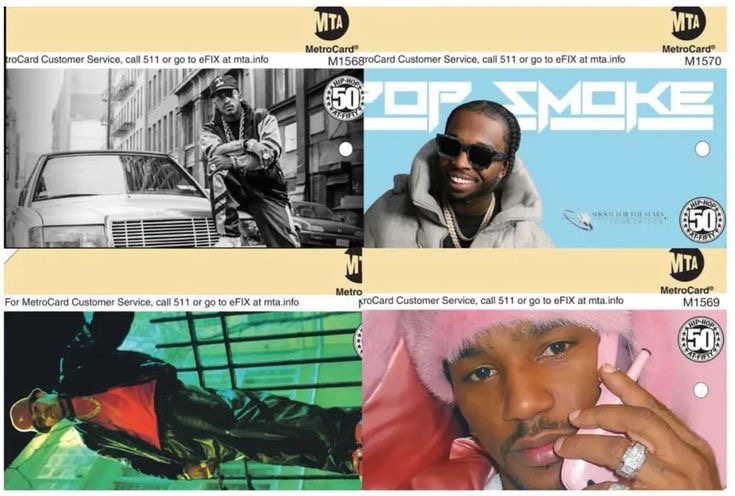

When I was purchased, I marketed artwork. I celebrated Jackie Robinson’s entrance into the league, or the World Series game between the Mets and the Yankees in ‘97. My prints reminded passengers about the U.S. Open, or how mesmerising our stations were, with some of my inaugural printings celebrating Grand Central Station and Times Square. I worked with the New York Philharmonic and Lincoln Center, and when Madagascar 2 dropped, everyone who loved Marty and Gloria could go to the Bronx Zoo for a discounted price. Because I told them about it. You—what do you do? Who do you praise? Like, deadass, I highlighted musicians, the back of my cards an appraisal to 50 years of Hip Hop, the Bronx’s potluck cultural attribution, and we celebrated the rhythms and rhymes from LL Cool J, Rakim, Notorious B.I.G., and at the Canarsie stop, drill lovers could grab my Pop Smoke printing. I was a keeper of David Bowie and K.I.S.S., and even dapped up the boys at Supreme, skaters in Washington Square and Tompkins attempting fakie-pop-shove-its with me in their JNCO jeans.

I was a requiem for arts and culture. I was—I am, an extension of printed media.

I was a requiem for arts and culture. I was—I am, an extension of printed media.

New York, the place dreams flow out of potholes, and busy train carts make perfect performance halls for street dancers, all of its liveliness and peculiarity condense into your negative space. Your shadows swallow what was left of our sun. I am cobalt and mustard, I share the colors of the Knicks and the passing B38 buses, and you are a reminder that this little island we enlarged is dying. In July, it was announced that I should look forward to dying. And you’d be my predecessor. Gentrification.

To the New Yorkers with five-borough blood bursting through their veins, I offered them one last thing that didn’t have to change. When Chinatown’s recreational centers were stockpiled, and Jamaica Avenue’s Colosseum constructed, and treasured soul food spots were turned into corporate Macchiato-Cortado-Latte-Matcha-Milk-bullshits, I let those who grieved their forever-morphing corners to relish in its remains. And when this city was rough on its impoverished, I loved them the most. I was carried in envelopes as a two-way pass for neglected youths and houseless teenagers after therapy sessions. I was in bundles at the 125th Street Station and Jamaica Center, when the hustle needed hustling, the platform’s associates pitching to families an exchange of two dollars for one of their rides. The associates swiping, and swiping, and swiping: “Nah, just one second, it’s just—alright, you good.”

I’d been a keeper of the old New York; the stoop-sitting, fire-hydrant popped, block party, OGs hitting their ones and twos outside the deli at two-three-four-maybe-even-five o’clock in the morning, Spike Lee, New Jack City, East v. West Coast rap scene, with the kiki ballroom underground and the counterfeit Louis-Prada-Gucci sold on Canal. What do you contribute to?

What do you do during an emergency? When 9/11 collapsed bodies and buildings, the spirits of the city—the city’s spirit dejected, I was a faith-clutch during an estranged commute home. I know mothers who retrieved their jaundice-recovered babies, the mothers transporting by way of the Q88, coming from Elmhurst Hospital. I accompanied them in the seat over. What do you do during a storm? After Hurricane Sandy demolished beaches and the houses closest to them, I gave them a map of assurance to come back when the Rockaways were recovered. After our 2016 election, when nihilism and fear cannibalized the nation and chewed our apple rotten to its seeded core, I sent out fifty-thousand versions of myself dedicated to Barbara Kruger. In 2017, I asked my people:

- Whose hopes?

- Whose fears?

- Whose values?

- Whose justice?

- Who is healed?

- Who is housed?

- Who is silent?

- Who speaks?

I wanted them to know I empathized with their worries of the oligarchy becoming. In 2025, oligarchy is not a crackle ahead, it fires now. Our fruit basket ablazes. And if you replace me, what is it that you will do? New York, we’ve built it on the beaten back of the Black American and the Immigrant’s swollen fingers. New York, floods with a copy-and-paste man in a mask, prying the platform for those he can devour: mommas perusing through their train carts with their traveling deli kiosks and toddlers who shout, “Chicles! Chocolates!” or aunties reading their bible as they wait for new customers to eye their crochet beanies. Then there’s the need for permits, and licenses, and warrants, and IDs, and passports, and handcuffs, and theft, and kidnapping, and bystanders wondering who told ICE they could play God, as if God did not create Cubans and Haitians. How do you invigorate their souls after? How do you carry the torch?

By December, they will stop printing me. And eventually, my momentum will be capitalized, my myriads branded over secondhand selling sites, and what used to be a totem for the workers becomes an item of the elitist. You are crippling me into my worst nightmare, I’ll be in the hands of those who’ve never understood me, instead of the 212- and 646-keepers who’ve made New York with all of its stovetop fires and profuse ambulances into a home. It is you who replaces me, the MTA who stops distributing me, and it is the possibility of forgetting which obliterates my infinite. Without me, the next generation will grow into a New York without its color. A New York that will outgrow its people of color? Its artistry which exhibits color? Its colors and its noises? Running marathons and mariachi performances? Rap battles? Its trending dances? The streetwear, its catching slang; its vibrato, staccato, bravado, Washington Heights cumbia/samba/bachata realness with its vendors pumping salivating simmers of empanadas and arepas?

Do you replace all of this? Because I wasn’t enough? Or because the culture isn’t?

I know I wasn’t always the fastest, and other times I malfunctioned, swiping the managing balance to zero. To those New Yorkers who’ve refilled on my behalf—yo, my fault, b.

But I’d never meant any harm.

And I know, OMNY, you can advance me, you may surpass this brief and wondrous life of mine, but what else will you do? To whom will you be of use to? I hope you know your time is also borrowed, but as I give mine to you, I pray you keep my city singing with all of the fervor to light or blow a trillion candles. On December 31, my life will come to a still. But if you’d be so kind, when it arrives to the 4th, please don’t forget to wish me happy birthday Stevie Wonder style.

I would’ve been 32.