Motherboards in 2023 at Krass Kultur Crash Festival, Hamburg.

Photo by Mario Ilic, courtesy of the artist.

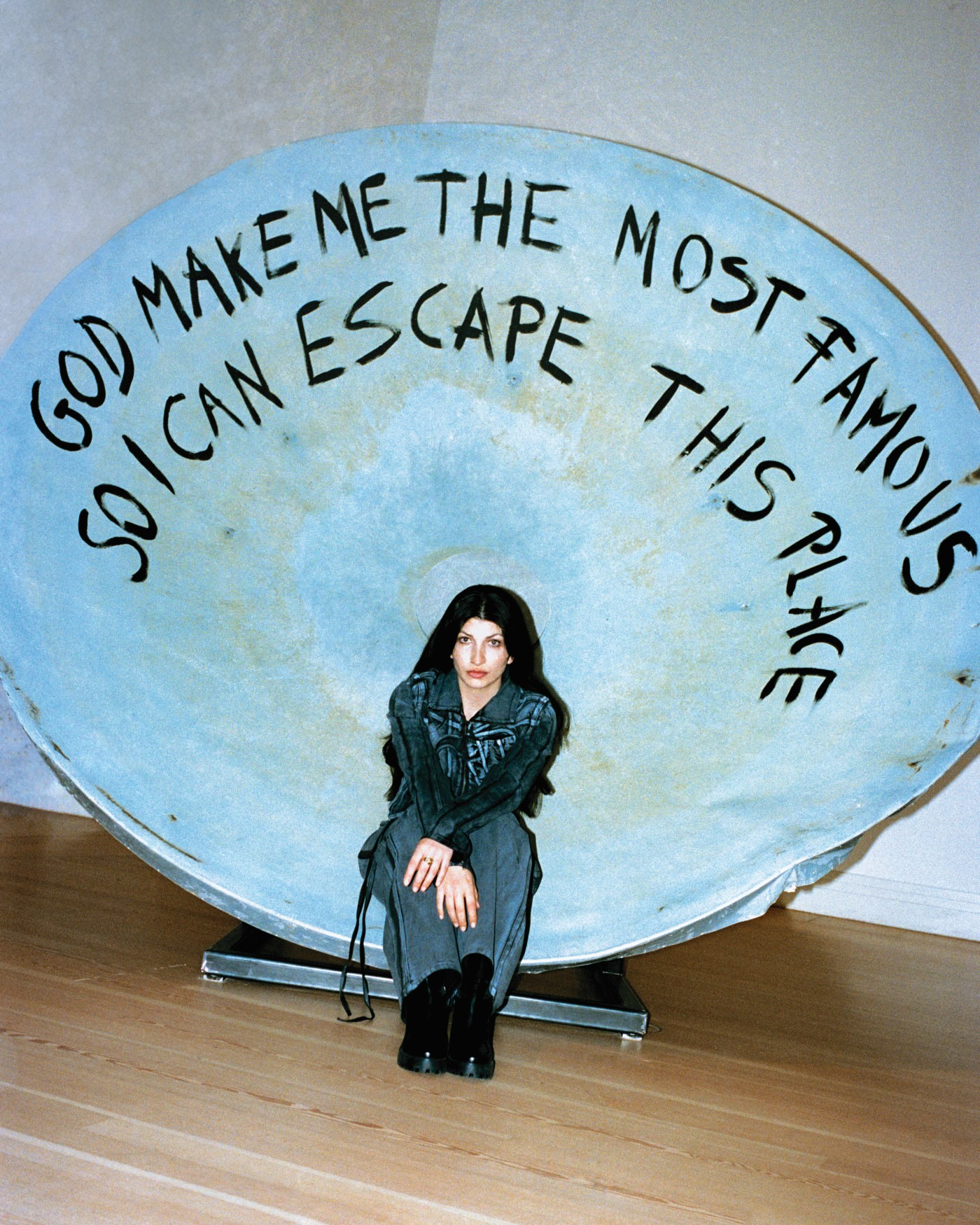

God Make Me the Most Famous So I Can Escape This Place

Selma Selman turns scrap and struggle into gold—a language of survival, desire, and resilience, now voiced in Istanbul.

By Gigi Surel

10.5.2025

I keep thinking about how contemporary artists don’t really have “fans” the way actors or musicians do. That needs to change. By now, I can admit I’m a Selma Selman groupie. I’ve seen her work in Berlin, Amsterdam, and London, and most recently in Istanbul with Motherboards (2023–ongoing), a live performance and installation in which Selman and her family extract gold from electronic waste.

It’s not like I ever set out or travel to see her, but somehow, I ended up spending more time with her work over the past year than with that of any other artist—reading, looking at, listening to, or even smelling what she is saying. Her work is visible in major institutions yet still somewhat under the radar in London, where I’m technically based. Selma Selman deserves fans. She’s a role model. She calls herself a transformer, sometimes an alchemist. Both descriptions fit.

Artwork by Selma Selman. Photo by Marjorie Brunet Plaza. Courtesy of the artist and ChertLüdde.

Artwork by Selma Selman. Photo by Marjorie Brunet Plaza. Courtesy of the artist and ChertLüdde.

Selman, born in Bosnia to a Roma family, is both artist and activist. She once called herself “the most dangerous woman in the world,” even creating a fragrance by that name for her exhibition at Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. It’s a provocation that contrasts with the soft-spoken kindness she presents in-person. But the phrase is more than bravado; it is a deliberate confrontation of the prejudice directed at her community. Beyond her art, she founded Get the Heck to School, an organisation that supports Roma girls worldwide who face social exclusion and poverty. Though she is often associated with her paintings on salvaged car parts, her practice is far broader. Spanning painting, performance, installation, and film, it is bound together by one central thread: transformation, whether of materials, social constructs, or cultural symbols. Often, it interweaves all of these at once.

Inscribed across a satellite dish in her 2023 solo exhibition at Gropius Bau were the words, “God Make Me the Most Famous So I Can Escape This Place.” In an interview with Vogue Adria, she described the piece as a self-portrait: not about past fears but the ones that press on us now, and the ones waiting in the future. According to her, it channels pop culture, Instagram, and social networks, but above all, her childhood desire for another life. Because of its simplicity, the work becomes strangely universal. We’re all searching for our place, and that constant searching brings its own low-grade anxiety. When I found out Selma Selman was performing Motherboards in my hometown, where I’ve been stuck for months due to family drama, I knew I had to be there. Suddenly, that satellite-dish inscription felt different. Istanbul is my place.

Photo by Lukas Korchan, courtesy of the artist and Vogue Adria.

Titled The Three-Legged Cat and curated by Christine Tohmé, the current edition of the Istanbul Biennial unfolds over three chapters. The first one gathers more than forty artists across eight venues along the Beyoğlu–Karaköy axis, all within walking distance. For this occasion, Selman and her family performed Motherboards at the Istanbul Museum of Modern Art, extracting the gold that she later transformed into a sculptural spoon now displayed at Zihni Han, one of the Biennial’s venues. There, shown alongside works by artists like Karimah Ashadu and Elif Saydam, the spoon rests against the wreckage of more than a hundred broken computers—cheeky, almost irreverent, a sharp reminder of how we assign value to objects, stories, and people, and how quickly we discard them. The gesture also traces a deeper lineage: Roma communities, including Selman’s own family, have long made their living from collecting and repurposing scrap metal—a form of labor often stigmatized yet central to her art. In Turkey, official figures estimate the Roma population at half a million, though activists believe the number to be closer to two million—it is a community that continues to face immense prejudice, and whose endurance Selman’s work so powerfully reframes.

By disassembling computers—motherboards, wires, CPUs—to extract 18-carat gold in Motherboards, Selman and her family turn the waste of the West into something magical. Selman had been building toward this for years. She began experimenting with these ideas at Rijksakademie Open Studios in 2023; even earlier, in 2018, she and her brother were already trying to make gold. She eventually developed a non-toxic extraction method and began performing the process live with her brothers and father. After one performance in Hamburg, she had enough to create a gold-covered nail, which she hammered into a wall. The project reached the U.S. in April 2025, when Motherboards premiered at MoMA PS1 as part of the group exhibition, The Gatherers. That show brought together fourteen artists who transform waste—extracting, collecting, and mutating discarded materials into new forms—to expose the failures of waste management and remind us how fleeting human life is compared to the long afterlives of the materials we leave behind. Gold runs through Selman’s work as both material and metaphor. In Roma culture, the substance carries weight, but Selman doesn’t romanticize it. Instead, she reshapes it into something else: a language for survival, destruction, desire, resilience, and hope. The work is also grounded in her own family history: her father made a living salvaging car parts.

Motherboards in Istanbul. Photo by Mete Kaan Özdilek, courtesy of the artist and IKSV.

Motherboards in Istanbul. Photo by Mete Kaan Özdilek, courtesy of the artist and IKSV.

Selman’s work is always personal. Money—its weight and necessity—runs through it. In her mahala, she had to “buy” her freedom by raising enough money so her family wouldn’t marry her off. That became her video work, “I will buy my freedom when” (2012–2018). She sold art, and even strands of her hair, and gathered thousands of euros—which her family then used to buy a Mercedes. I saw on her Instagram that her father—her Babo—passed away. He was the one who first taught her how to dismantle and reuse what others discarded, the one who sparked her early paintings on car parts and later joined her onstage to break down machines for gold. That lineage—of labor turned into art, of survival into transformation—runs through everything she makes. I’m going through my own difficulties with family now, and delving into her practice has helped me gain a perspective that is both reactive and transformative. That’s what I mean when I talk about artists needing fans. It’s not just admiration; it’s connection. I now find myself collaborating with my family in the very place I once prayed to escape. Seeing Selman do the same in Istanbul felt like gold.