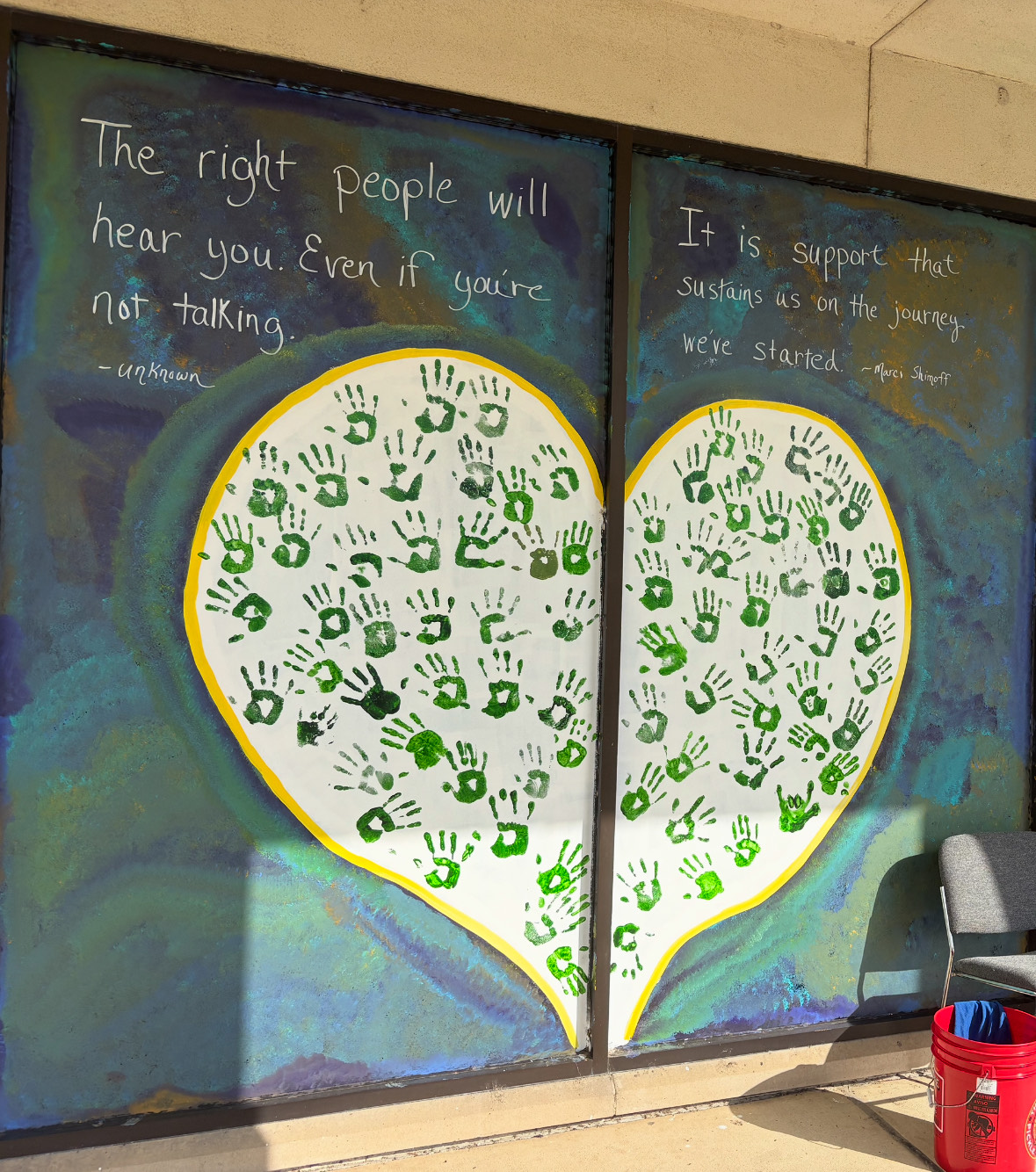

The Emotional Support Center in Kerrville, Texas.

All photos by Chloe Citron.

Uprooted

Notes on wreckage.

By Chloe Citron

10.17.2025

I’m grieving and I’m in Texas and it’s hot and the sun is very bright. I’m in the car with my father.

“Now here you can see the devastation,” he says, gesturing out the window. I look out the window, at heaps and heaps of gnarled overturned trees. We’re driving along the Guadalupe River, where months ago a flood ripped through the area, ravaging the landscape and claiming the homes and lives of so many people. For the last eight months, I’ve been volunteering with the agency my father works for in Texas doing fundraising to support the mental health of people living in the Hill Country. The work has taught me a lot about people and the support they need, especially after a crisis like this flood. I flew to Texas from my home in Brooklyn not only to visit the sites of the programs I’ve been fundraising for, but also to escape the chaos of a personal loss that had uprooted me in its own right.

Like the trees, which had been so deeply and strongly rooted in the ground, being forcibly removed by the strength of the floodwater. Just ripped out and made into a different kind of thing, a thing with less life and less nourishment. The force of uprooting can be so violent. It is no small thing, for trees and for people alike. Roots connect us to systems, systems that give us life and community. Here were these massive stacks of trees—exposed, piled up and hauled away by machines. Being hauled away by people. They had gone from being living and well connected beings, which provided shelter and shade, whole ecosystems…to debris.

What’s left in the wake of disaster is clean up. I’m realizing It’s never just the rush of the flood, the violence of the attack. When things go very wrong, it’s the clean up crew who show up in the wake that lasts far longer. The years that follow, the years of picking things up and carrying them away. Of rebuilding. The people who show up in that time are crucial.

And in the flood zone, people are showing up. The work they’re doing is not only the act of connecting survivors with supplies and resources, it is also being deeply concerned with their emotional state. They are going out to houses, driving out in ATV’s and cars and on foot—to see how people are doing. Letting them know “we aren’t going anywhere.” Checking in and building lasting relationships with individuals, to help guide them back to normalcy.

We drive down the road along the river. We’re going to see the different flood relief efforts. In Texas it takes so long to drive anywhere, but I am relieved to be in the car, being driven by someone else. Having my days structured by someone else. I wear the signature green t-shirt of the organization every day I am there, walking around matching with my dad. We’ve never matched before, but it is nice to not have to think about what to wear. As we drive, I allow myself to look at my reflection in the rearview mirror. I look kind of wild—eyes wide, skin flushed from the heat, hair long and a little snarled, laying against my green t-shirt. No matter the scale of a devastating event, we still eventually have to start washing our face and brushing our hair again. Letting myself melt into a collective effort makes the days go by easier. I am not just myself, I am one of many helpers in a green shirt. I break eye contact with myself and turn my gaze back to the river.

Finally, my dad and I pull into a parking lot to meet some of the employees who are handing out cooling towels, toys for children, snacks. I notice colorful kinetic sand on the table of supplies. Relief can look like many different things. To our right, two food trucks are giving out free barbecue and tacos. There’s this big gray van parked there, which looks very high-tech. They encourage me to take a look. I climb inside—it is spacious, and the air feels cool. They’ve been using these vans to drive around, and people who are hot and need a break from picking through debris can come inside. They can drink some water and receive therapy. Support on the go. If the people cannot come to you, you can go to them. The way people were showing up for each other created a wraparound effect, a safety net.

They tell me about one man who had jumped down into the riverbank to pull people out of the water and had been injured doing so. He didn’t speak English and was wary of seeking treatment. Many people in his community were distrustful of outside help because of the looming presence of ICE. Even after the flood. It took time for one of the Spanish-speaking members from the organization to gain his trust enough to help him. He received treatment for his injury, and the team also helped him pay for it. This connection allowed others from his community to receive much needed resources. I learned how outreach in times like these isn’t just manpower and money—it’s also language. This man required a translator, but also someone who simply knew the right thing to say. Trust is a very sensitive thing, alive and fragile. It must be tended to, and so easily it can be washed away by a powerful current. It seems to me that you have to gain a person’s trust before you can save their life.

We depart from the parking lot and continue driving. All along the narrow roads are signs with messages spray painted on them with sayings like, “You can do it! We will help,” and, “Hope wispers!” Yes, without the h. This evolves into a mantra for me while I’m in Texas, and even now I repeat it in my head when I need to hear it: “Despair is loud. Hope wispers.” Without the h.

Every day I am seeing how much helping other people matters. Being there for people, for their feelings, makes a difference. Not just interpersonally, but structurally. The infrastructure of our communities, our businesses, the health of our families are all affected by a helping hand.

Hands are the first thing I see when we arrive at our next stop, the Emotional Support Center in Kerrville. It’s a place where people who have been affected by the flood can come for a wide range of support services. The front of the building is covered in painted handprints. People who come to the center can paint their hand and leave its mark on the windows. My eyes rove over the windows. Hands and hands and hands. We go inside. Immediately I notice a book for children with the title, “H is for helping hand.” The idea of teaching children about community support following a disaster seems so hard and abstract, but suddenly, these people were just in it, and it had to be done.

Inside, I learn that the first responders who had seen some of the worst of the aftermath were being actively supported, attending counseling sessions. I am struck by this—there is a cost to saving others, a price to be paid for the support you give. But care doesn’t stop like the end of a rope, it goes on and on like the roots of a tree—it is a network. And the network at the Emotional Support Center includes so many methods of care: art programming, childcare, community outreach.

Looking around, I keep thinking how nice everything is. I’m surprised. Beauty and comfort don’t always seem like the first reserves after a disaster. But then, why wouldn’t they be? We have some control over our environments, to affect the way we feel. Earlier as we were driving we had passed a sign for an aquifer that said “environmentally sensitive recharge zone”—this is what the emotional support center feels like to me.

The counseling rooms are cozy and warm. The lovely people who work in the center tell me about how a local furniture store donated couches and blankets, and that they’re even getting essential oil diffusers soon. There are also lots of stuffed animals everywhere. Items that heal might seem just like objects until you need them, and then they are deeply, absolutely necessary. You’d be surprised by what can be a lifeline. A stuffed cow. A taco. A person, simply sitting with someone in the wreckage and being there.

We listen to some of their stories about the people they’ve met in their efforts. I hear about a man who had lost pretty much everything in the flood. The team stepped in to help, and they found a woman through Facebook who was able to donate a washing machine, a fridge, and other essential items to the man. In delivering these to him, the team learned that he’d lost his son the year before to suicide. In the last year, he had taken time off work to dedicate himself to living his life the way his son would have wanted, to live differently. Then, the flood happened. And almost all of his son’s belongings had been destroyed. It is overwhelming to hear about. Personal loss doesn’t disappear in the face of collective loss—it’s intertwined, threaded together and blasted open. Everyone is walking around with some amount of wreckage they’re sorting through. The keepsakes and the documents and the appliances, all these objects we rely upon. When we lose things, it forces us to do a sort of recovery process—what is left? The team members tell me they’ve been checking in on the man who had lost so much, and that he’s opening his mind up to mental health treatment. I thought about this man’s story, how universal it felt—while any of us are trying to search through the wreckage for some remnant of meaning, it helps to have someone there who cares whether we find it.

We leave the center and continue on. More driving then, and more thinking. I’ve been so consumed by the places I can’t go back to, the people I can’t see anymore. But imagining them being just completely washed away, destroyed and irretrievable…the scope of that feels impossible to wrap my head around.

Sometimes disaster seems so random. The timing, the strangeness of it all. After driving for so long, I’m lulled into a quiet, still state. I am jolted out of this by the sight of a giant pig. I ask my dad to pull over so I can go look at him up close. I guess he is more of a hog than a pig. He really has some size to him. Later, I learn that the pig had survived the flood by floating. He had floated away and then…he had returned. Just like that. He knew the way home. Ten bodies had been recovered on this property, but the pig survived. It seemed so surreal and almost cruel (the dumb luck of it), but here he is, alive and caked in mud and happy. And here I am. Here I am, alive. Sunburnt and my hair unbrushed and letting myself lean on other people. I’m learning to let other people be there for me—and in turn, learning that by being there for others, my pain will be eased. My friend told me on the phone that by supporting me through this time, it helps her because she will be better prepared if she ever goes through the same thing.

The last night of my visit I sit alone in the parking lot of an Outback Steakhouse for a few minutes waiting for my dad. It is my first moment alone in several days. I watch flocks of birds flying through the sky, gliding and spinning. Somehow they know how to stay together in rhythm. I watch the sun setting, and I start to cry. And for the first time, I’m not crying about my loss itself. I am crying because I am changing. Because now I understand that this had to happen. I had to change. Because that’s apparently the way of the world, of nature. Change. Destruction, and then rebuilding. It’s beginning again and again and again. Hands and hands and hands.