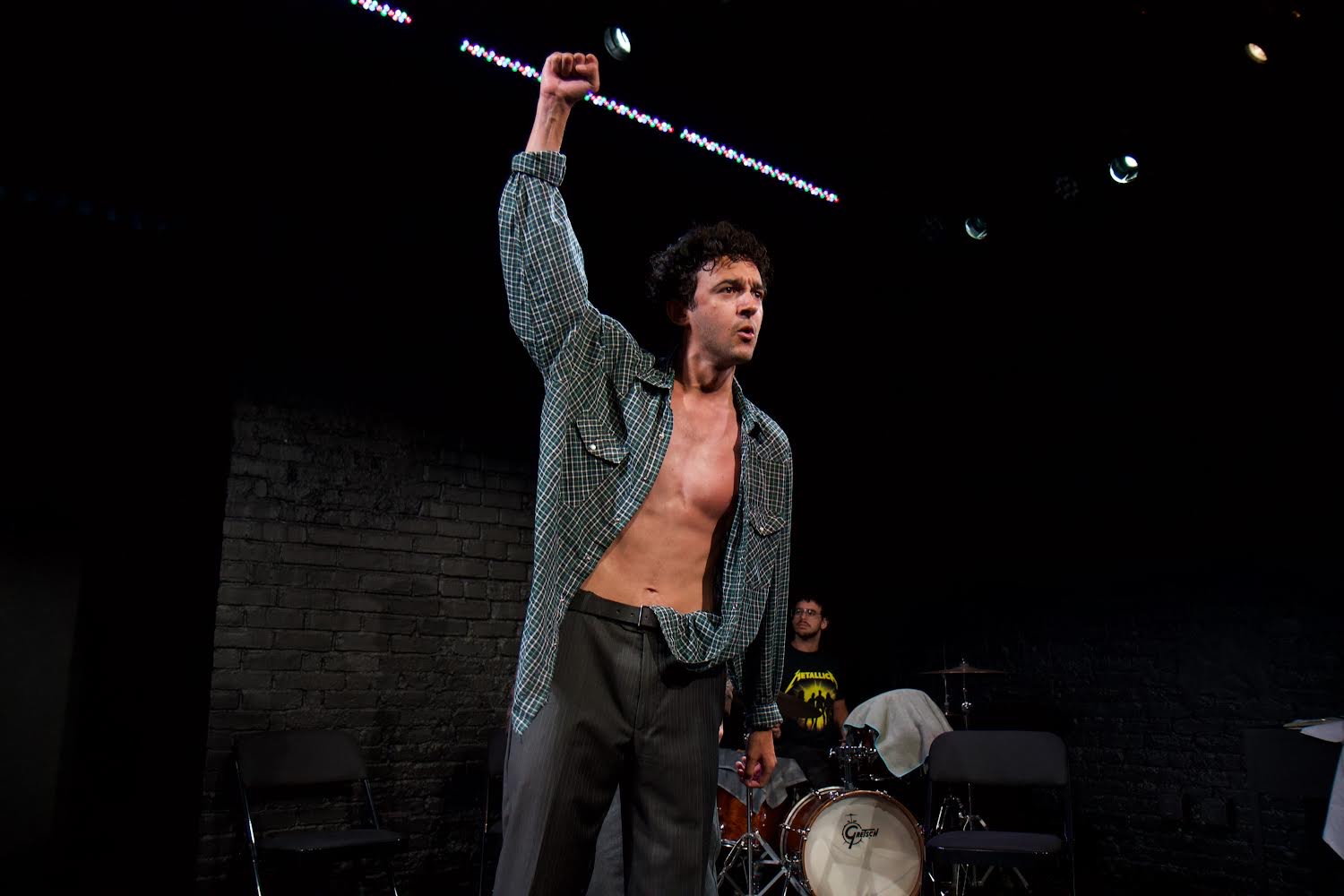

Ahmad Maher as Agate in Waiting for Lefty. Production photo by Mari Eimas-Dietrich.

90 Years Later, We’re Still Waiting

A new revival of an old play resonates at The Flea Theater.

By Claire TUmey

08.27.2024

When it comes to producing theater in 2024, I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t a staunch advocate for new works. While, statistically speaking, new works do outnumber revivals in each production season in New York, they are still likely to lack some degree of originality. In the past 30 years, 82% of new Broadway musicals were adaptations of existing material. So when I walk into a revival of a play, I’m pretty stringent in my hope that I’ll see a fresh take or a strong perspective on how the piece can relate to modern times. As I descended into the black box theater in the basement at The Flea, an off-Broadway house located about as far downtown as you can go before Manhattan loses most of its personality, I had a feeling the revival I was about to see would keep that hope alive.

Waiting for Lefty is an unapologetically leftist piece of theater about strikes. The Flea itself is quite the interesting choice of venue for a show like this. You might notice, as you go to buy tickets to see a show there, that the website URL insists the performance venue is “The New Flea.” No doubt, this is in an attempt to distance the space from its old management (see any online article referring to The Flea’s 2020 existential crisis as “The Fled”). The Flea has thankfully come out on the other side of the mass exodus of 2020 as a space that uplifts and centers the voices of Black, brown and queer artists (the same voices the Old Flea came under fire for attempting to silence).

But this play isn’t exactly about artists fighting for their autonomy against powerful producing bodies (or, in a more metatheatrical way, isn’t it always?). Written in 1935 by first-generation American dramatist Clifford Odets, Waiting for Lefty centers around one of the more notable strikes in New York City history: the Taxi Driver Strike of 1934. But, as explicitly stated by producer Ben Natan in the program, the issues these characters were grappling with 90 years ago are not only similar to the class struggles we are experiencing in American society today—they are directly and eternally interconnected. As I sat in the back row, my legs dangling as if I was about to blast off at Six Flags (peculiarly, the floor does not meet your feet where it should in that row of the theater), I tried to think of when I last hailed an honest-to-God NYC yellow cab. For the longest time, I had told myself that rideshare apps were cheaper. I learned that that belief migrates between true and false depending on the day, but the downright convenience of pressing a button and watching a car appear before me is undeniable (ah, convenience: the downfall of the delicate symbiosis that depends on us not concerning ourselves with all of our modern shortcuts.)

Notice how easily I fall into the trap of speaking about the objects—cars, apps, things things things—not the human being behind the wheel. Members of the working class in America rely on unionization as a means of asserting their basic human rights, one of those being the simple demand to be seen and heard by those who rely on their services every day. There hasn’t been a year since 1881 in which the United States HASN’T had a percentage of its population actively on strike (and 1881 is only the year they started recording this statistic). Notably, we’re coming up on the one-year-anniversary of the end of 2023’s WGA and SAG-AFTRA Strikes. And there’s a chance you might’ve seen longer wait times or even Uber maps completely barren of available drivers as you were trying to find a ride home from your Valentine’s Day dinner this past February; that was the most recent time Uber and Lyft drivers went on strike, citing unfair wages and driver safety concerns as their impetus. Capitalist realism—a term coined by British philosopher Mark Fisher to represent the misguided belief that, because this is the way things are, this is the way things are meant to be—seems to demand that wherever the few corrupted by corporate greed try to operate under the guise of “growth and change,” there will always be the many bargaining with how they live—or refuse to live—with the material, emotional, and spiritual consequences of exploitation.

From the very first lines of the play, it’s evident that Odets did not want the audience to just sit back and take the work in as an observer. Instead, a rousing opening monologue is delivered directly to the audience by Union Boss Harry Fatt, played by a swaggering, unapologetically man-spreading, and vocally commanding John Austin. He puffs on a cigar as he assures us, audience members-turned-implicated Union Members, that our concerns are unfounded: the “man in the White House” is on our side, and therefore, we shouldn’t strike. My mind wandered to the political theater I had just witnessed one night prior, when Kamala Harris accepted the nomination from the Democratic Party in an emotional whiplash-inducing speech that promised sweeping social justice and the “most lethal fighting force in the world” in what felt like the same breath (the speech was 37 minutes long—one of the shortest nomination acceptance speeches in US history).

Woven in between moments from the union meeting are six vignettes, featuring a cast of everymen-and-women facing varied struggles, highlighting some difficult truths about American politics—well, difficult truths about the politics of the American Elite, who, as these vignettes show, have built a society that keeps a firm control over the masses. Director Alex Pepperman’s use of the ensemble reiterates this notion: even in the most intimate vignettes, which depict the impact of capitalism on the personal lives of the proletariat, there are always other actors on stage, looming in the shadows (Harry Fatt, most often, puffing his cigar, taller in stature than every other player). Their presence reminds us that not a single aspect of our humanity isn’t touched by our connection to and dependence on an economic system that devalues our need for communal care.

If the central argument of the play is “To strike, or not to strike,” each vignette implores us—albeit, quite heavy-handedly at times—that the answer is, “Strike, obbbvviousssllyyy.” Capitalism and her offshoots—Greed, Desperation, Nepotism, Discrimination, and Capitulation—are on display in these short scenes. Actors Maya Jeyam and Txai Frota handle the complicated nature of a marriage strained by financial hardship with care as overworked and underpaid Joe and Edna, a taxi driver and his wife. I was sick to my stomach watching Michael Aurelio, as chemical company Big Biss Fayette, exhibit what happens when one chooses violence (and sociopathy) as a means to get ahead, as he unsuccessfully tries to persuade unevenly tempered lab assistant Miller (played by Ahmad Maher) to take part in developing a weapon of mass murder. Interestingly enough, I saw a thread of connection in Aurelio’s next character, Sid, who wants to start a family with his young girlfriend, Florence (played by an effervescent Milena Makse), but cannot cope with how his position as a cab driver will never provide for the life they dream of. Despite the two actors’ impressive chemistry, Aurelio exhibits that same glimmer of detachment as Sid implores Florence to be realistic. It reminded me of one of philosopher Paulo Freire’s assertions in his landmark work Pedagogy of the Oppressed: Oppression demands that the Oppressor forgoes his humanity just as much as the oppressed. Both Fayette and Sid must detach themselves from what makes them fully human (empathy and love, respectively) in order to cope with their realities. This was a memorable choice, both in acting and casting, that I’m still lingering on.

In the final vignette, Marcus X. Stewart gets his star turn as Barnes, who is charged with breaking the news to the younger Dr. Benjamin (played by Makse, who, like all actors in this production, is able to successfully distance this role from her previous one) that the hospital they work at must close its charity ward. But that’s not all—he later informs her that they lost a patient at the hands of some higher-up’s incompetent nephew. As Barnes states in my favorite moment of the night, “In a rich man’s country, the true self is buried.” I could practically see the layers Barnes himself is buried under as he exasperatedly tries to reason his way through one piece of devastating news after another.

In between each of these vignettes, the play pulls us back into the “present” of the Union meeting, facilitated in great part by Amara McNeil’s lighting design, which almost acts as a director itself in the way it cues and sustains an emotional state for each vignette. Two players even live between worlds, traveling the aesthetic distance between audience and actor. Cito Mena, as a member of the ensemble, delivers two rousing moments of performance that really make an audience member ponder, “Wait, do I, too, have clearance to get up on stage and advocate for myself, to share what I know?” (I warrant I couldn’t do it as full-throated as Mena’s Union Member, but I have a standard to aspire to!) Oscar Javier, the Musician, plays the most roles of anyone in this production: a doorbell, a gramophone, a telephone, and beyond all that, a pacemaker, an omniscient narrator of sorts.

I was in The Flea at 7pm and out before 8:15 (while this play was written during the Great Depression, I feel a one-act is the perfect length for 90% of theatrical experiences in the digital age). During that time, I waited for a Lefty that never came. It made me think about all the great people’s movements in history that fell into the trap of waiting on some single figure of exceptionalism, one single personality to unite under: the kind of organization that only emulates the oppressive forces these movements seek to overthrow. I won’t spoil everything about the circumstances of Lefty’s disappearance, but what I will say is that the play leaves one wondering why we were ever waiting for him in the first place. While this downtown revival of a 90-year-old play offers a very specific answer for what to do as an exploited member of a taxi-driver’s union in the 1930s, it leaves us only with questions as to what we might do in the 2020s to fight the oppressive forces ensuring that the rich get richer while the poor struggle to survive. That is, of course, assuming that members of the audience identify with the working class. If that’s not necessarily true, perhaps there’s some good to come of getting the average New York theater-goer to pause, and to really listen to the angry voices at the end of the play yelling, “Strike! Strike! Strike!”

Waiting for Lefty, produced by Soho Shakespeare Theatre and Small Boat Productions, runs at The Flea (20 Thomas St.) until September 8th. Tickets available at thenewflea.org/events. If you take a car, ask your driver their name and how they’re doing today!