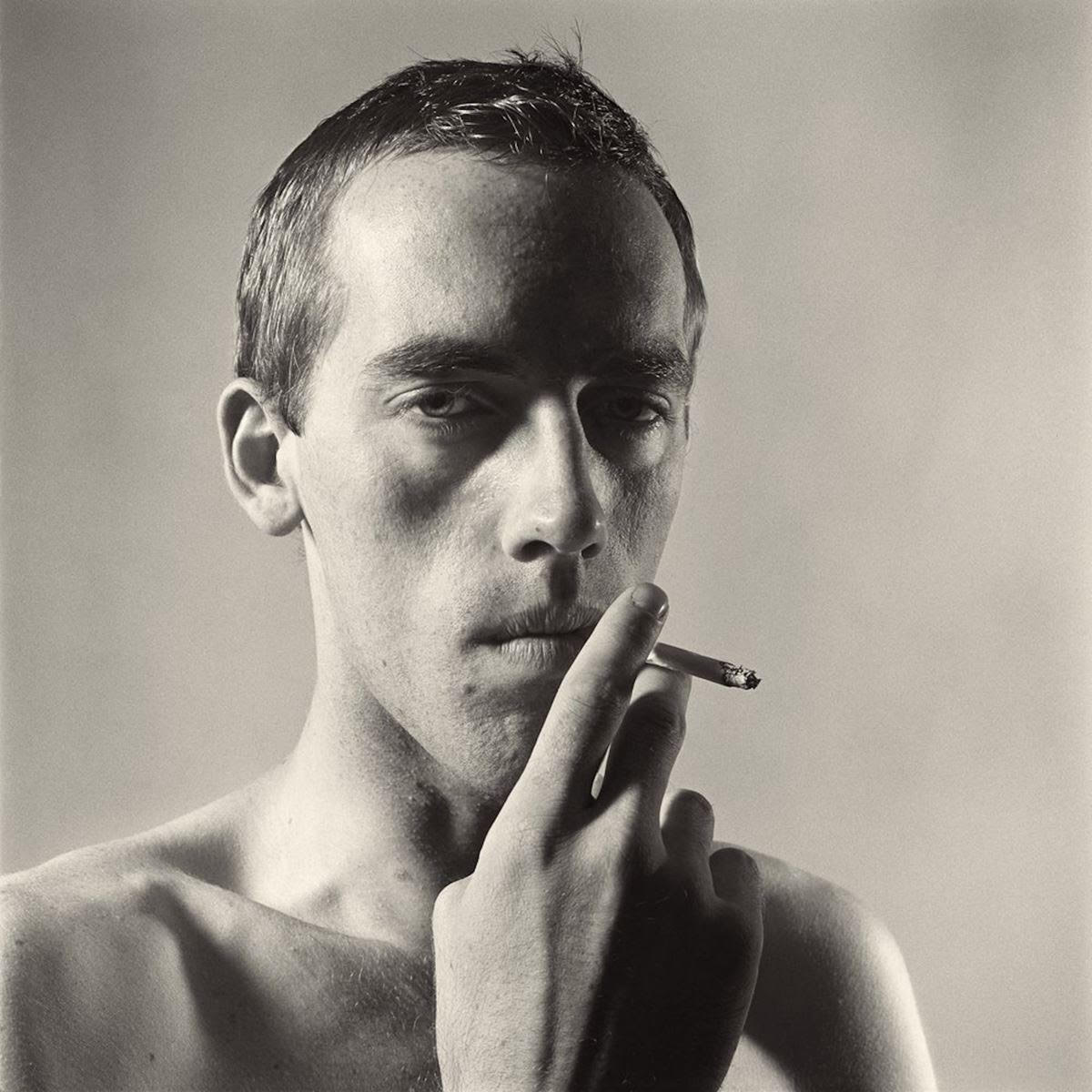

David Wojnarowicz by Peter Hujar, 1981

In the graphic novel 7 Miles a Second, an extremely tall, lanky man wearing black sneakers, a white shirt, jeans, and a brown jacket has his right fist raised—ready to swing. His left fist is extended through one of the two spires of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, which is crumbling to the ground. Along the side of the page are 246 words making up a single sentence. No colons, no commas, no em dashes—only one period.

The subject and narrator is David Wojnarowicz, whose raw descriptions (many of which used no punctuation) of his childhood as a hustler in Times Square, cross-country hookup travels, and battle with AIDS would become praised for, and relegated to, a single emotion: rage.

Rage permeates the most recent major depiction of Wojnarowicz: the documentary All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. The film, which details photographer Nan Goldin’s upbringing, work, and more recent fight against the Sackler family, deals with the loss and anger she and other artists went through in a time riddled with addiction and AIDS. Wojnarowicz comes into the film with his work in Goldin’s controversial exhibit Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, fighting against political and legal backlash, as well as his fiery speech at the funeral of actor-author Cookie Mueller.

Rage is apparent throughout Wojnarowicz’s work, as the title of his film—A Fire in the Belly— indicates. The film and its association with rage is how Village Voice critic Cynthia Carr opens her 580-page biography of Wojnarowicz. Carr describes two reactions to the film: the Catholic League denounced it as sacreligious for depictions like fire ants crawling over a bloodied crucifix, and fans declared the film to be a glimpse into the suffering that AIDS caused.

But Carr’s introduction (titled “The Truth”) is meant to display the public misconception around Wojnarowicz and his work.

“Even when he aggravated the powerful, David never saw his work as provocation. He saw it as a way to speak his truth, a way to challenge or at least illuminate what many accept as given.”

Though rage and provocation are often not Wojnarowicz’s intended messages, his work can certainly be received as such. As Carr’s interviews with Wojnarowicz and the many people around him express, Wojnarowicz’s childhood remained a core struggle that he contended with in his work throughout his life.

Wojnarowicz fabricated much of his upbringing. During Carr’s interviews, many of Wojnarowicz’s relatives, friends, and lovers were shocked with his supposed stories. Some, such as the only high school teacher Wojnarowicz ever liked, didn’t even know the famous artist he became. Others didn’t know he was gay. And many didn’t know he had been a sex worker in Times Square since he was about 13 or 14.

Wojnarowicz’s lies did not stop Carr from laying out her version of his childhood. Born the third child to a seaman named Ed and a young woman from Australia named Dolores, Wojnarowicz’s only time with his entire family was a few years in Red Bank, New Jersey.

Ed was a chronic drunk who physically abused his entire family almost daily, blamed an eight-year-old Wojnarowicz for being sexually assaulted by a high schooler, and kidnapped the kids following divorce court. This led Dolores to move to Manhattan, where she worked as a model—that is, until the kids found her number in a phone book and ran away from their father.

Wojnarowicz’s years working as a hustler in midtown while living in Dolores’s apartment were some of the most formative and fabricated of his life. Stories of mob leaders, warehouses full of potential clients, other hustling teenagers he met on the streets, and multiple times where he was almost killed shift from memoir to memoir, interview to interview, and throughout Carr’s biography.

What matters most in Carr’s retelling is why Wojnarowicz lies about his early life. Even his most candid writings and pieces remain shrouded in fiction. Only bits of truth stick out of the fibs to show there’s much more underneath.

As he grew older, he saw friends, mentors, lovers, and himself contract a virus that tortures both its victims’ bodies and the perceptions the world has of them. Even while he may not have intended it to do so, his work reflects his rage—rage he could not process, rage he grew up with, and rage he endured in his final moments. Wojnarowicz was certainly speaking his emotional truth, but his truth was forever embedded in unconscious rage.

Carr found that Ed had two more kids after his first three ran away to the city: a son named Pete and a daughter named Linda, both of whom Ed continued to abuse. One day, a couple weeks after standing up to his father for the first time, Pete walked down into the basement to find his hanged father. After cutting him down, and crying for only about 10 seconds, Pete told Carr that the weight from years of abuse suddenly lifted from his shoulders. Wojnarowicz never seemed to feel that same relief.

Interviewing Wojnarowicz about his past was evidently difficult for Carr, and his two siblings were no less challenging. Answers from all three—on timelines, events, opinions of their parents, almost anything from their upbringing—often differed from one another. Carr supposes, particularly regarding Wojnarowicz’s older sister Pat, that blocking out their trauma blurred almost all aspects of their childhood.

Though Wojnarowicz may be similar to Pat in some regard, he undoubtedly adopted the creation of his own myths for a different purpose. Carr said that one quote from the book Christopher and His Kind, which Wojnarowicz’s ex-boyfriend Alan gave him following their separation, resonated with Wojnarowicz for the rest of his life:

“Anything one invents about oneself is part of one’s personal myth and therefore true.”

We will never know how much truth is in Wojnarowicz’s work or whether he truly didn’t intend to be provocative. But for Wojnarowicz, his story—though filled with rage, fabrications, political rebellion, and contradictions—is nonetheless true.

David’s Rage

With the East Village’s 1980s fight against AIDS Depicted in the film All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, it is important to reflect on a pioneering figure: David Wojnarowicz.

By Kristian Burt

06.07.2023

In the graphic novel 7 Miles a Second, an extremely tall, lanky man wearing black sneakers, a white shirt, jeans, and a brown jacket has his right fist raised—ready to swing. His left fist is extended through one of the two spires of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, which is crumbling to the ground. Along the side of the page are 246 words making up a single sentence. No colons, no commas, no em dashes—only one period.

The subject and narrator is David Wojnarowicz, whose raw descriptions (many of which used no punctuation) of his childhood as a hustler in Times Square, cross-country hookup travels, and battle with AIDS would become praised for, and relegated to, a single emotion: rage.

Rage permeates the most recent major depiction of Wojnarowicz: the documentary All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. The film, which details photographer Nan Goldin’s upbringing, work, and more recent fight against the Sackler family, deals with the loss and anger she and other artists went through in a time riddled with addiction and AIDS. Wojnarowicz comes into the film with his work in Goldin’s controversial exhibit Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, fighting against political and legal backlash, as well as his fiery speech at the funeral of actor-author Cookie Mueller.

Rage is apparent throughout Wojnarowicz’s work, as the title of his film—A Fire in the Belly— indicates. The film and its association with rage is how Village Voice critic Cynthia Carr opens her 580-page biography of Wojnarowicz. Carr describes two reactions to the film: the Catholic League denounced it as sacreligious for depictions like fire ants crawling over a bloodied crucifix, and fans declared the film to be a glimpse into the suffering that AIDS caused.

But Carr’s introduction (titled “The Truth”) is meant to display the public misconception around Wojnarowicz and his work.

“Even when he aggravated the powerful, David never saw his work as provocation. He saw it as a way to speak his truth, a way to challenge or at least illuminate what many accept as given.”

In “Untitled (One Day This Kid…),” a black-and-white drawing of a boy—slim, freckled, smiling with two bright-white buck teeth, and wearing overalls strapped over a patterned button shirt—is encased in walls of text. The text lays out the boy’s future, which begins with his sexual awakening and ends with the innumerable injustices he will face that, in one way or another, will result in his death.

Though rage and provocation are often not Wojnarowicz’s intended messages, his work can certainly be received as such. As Carr’s interviews with Wojnarowicz and the many people around him express, Wojnarowicz’s childhood remained a core struggle that he contended with in his work throughout his life.

Wojnarowicz fabricated much of his upbringing. During Carr’s interviews, many of Wojnarowicz’s relatives, friends, and lovers were shocked with his supposed stories. Some, such as the only high school teacher Wojnarowicz ever liked, didn’t even know the famous artist he became. Others didn’t know he was gay. And many didn’t know he had been a sex worker in Times Square since he was about 13 or 14.

Wojnarowicz’s lies did not stop Carr from laying out her version of his childhood. Born the third child to a seaman named Ed and a young woman from Australia named Dolores, Wojnarowicz’s only time with his entire family was a few years in Red Bank, New Jersey.

Ed was a chronic drunk who physically abused his entire family almost daily, blamed an eight-year-old Wojnarowicz for being sexually assaulted by a high schooler, and kidnapped the kids following divorce court. This led Dolores to move to Manhattan, where she worked as a model—that is, until the kids found her number in a phone book and ran away from their father.

Wojnarowicz’s years working as a hustler in midtown while living in Dolores’s apartment were some of the most formative and fabricated of his life. Stories of mob leaders, warehouses full of potential clients, other hustling teenagers he met on the streets, and multiple times where he was almost killed shift from memoir to memoir, interview to interview, and throughout Carr’s biography.

In ‘Untitled (Face in Dirt),” crumbled and powdered dirt covers the subject of a black-and-white photo. Two bushy eyebrows, two closed eyelids that seem tranquil despite the earth caked on top of them, two flared nostrils blowing the dust away, two dry and cracked lips, and two bright-white buck teeth protrude from the ground to indicate a whole head is resting beneath.

What matters most in Carr’s retelling is why Wojnarowicz lies about his early life. Even his most candid writings and pieces remain shrouded in fiction. Only bits of truth stick out of the fibs to show there’s much more underneath.

As he grew older, he saw friends, mentors, lovers, and himself contract a virus that tortures both its victims’ bodies and the perceptions the world has of them. Even while he may not have intended it to do so, his work reflects his rage—rage he could not process, rage he grew up with, and rage he endured in his final moments. Wojnarowicz was certainly speaking his emotional truth, but his truth was forever embedded in unconscious rage.

Carr found that Ed had two more kids after his first three ran away to the city: a son named Pete and a daughter named Linda, both of whom Ed continued to abuse. One day, a couple weeks after standing up to his father for the first time, Pete walked down into the basement to find his hanged father. After cutting him down, and crying for only about 10 seconds, Pete told Carr that the weight from years of abuse suddenly lifted from his shoulders. Wojnarowicz never seemed to feel that same relief.

In the film Silence = Death, a slim, long-faced man with an unremarkable haircut stares straight into the camera with a harsh yet relaxed look. His lips look soft and cordial, despite 11 stitches pulling them shut and streaks of blood lining his chin.

Interviewing Wojnarowicz about his past was evidently difficult for Carr, and his two siblings were no less challenging. Answers from all three—on timelines, events, opinions of their parents, almost anything from their upbringing—often differed from one another. Carr supposes, particularly regarding Wojnarowicz’s older sister Pat, that blocking out their trauma blurred almost all aspects of their childhood.

Though Wojnarowicz may be similar to Pat in some regard, he undoubtedly adopted the creation of his own myths for a different purpose. Carr said that one quote from the book Christopher and His Kind, which Wojnarowicz’s ex-boyfriend Alan gave him following their separation, resonated with Wojnarowicz for the rest of his life:

“Anything one invents about oneself is part of one’s personal myth and therefore true.”

We will never know how much truth is in Wojnarowicz’s work or whether he truly didn’t intend to be provocative. But for Wojnarowicz, his story—though filled with rage, fabrications, political rebellion, and contradictions—is nonetheless true.