Krista Gay, “You Look Just Like Mama from a Distance” (2024). All images by JSP Art Photography.

Fictitious Family

seven artists interrogate narrative building through family photos.

By Theodora Bocanegra Lang

3.29.2025

In Time and Time Again: Fiction, Family, and Photography at Hercules Art Studio Program, an artists’ residency in lower Manhattan, seven artists interrogate the forms of narrative building that appear in our own lives through family photos. Each artist relies on a level of familiarity between each other and their audiences. The rapid shifts in photographic technologies and norms throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries quickly date the techniques used and referenced in the work. What viewers carry with them are their own experiences with the same source materials.

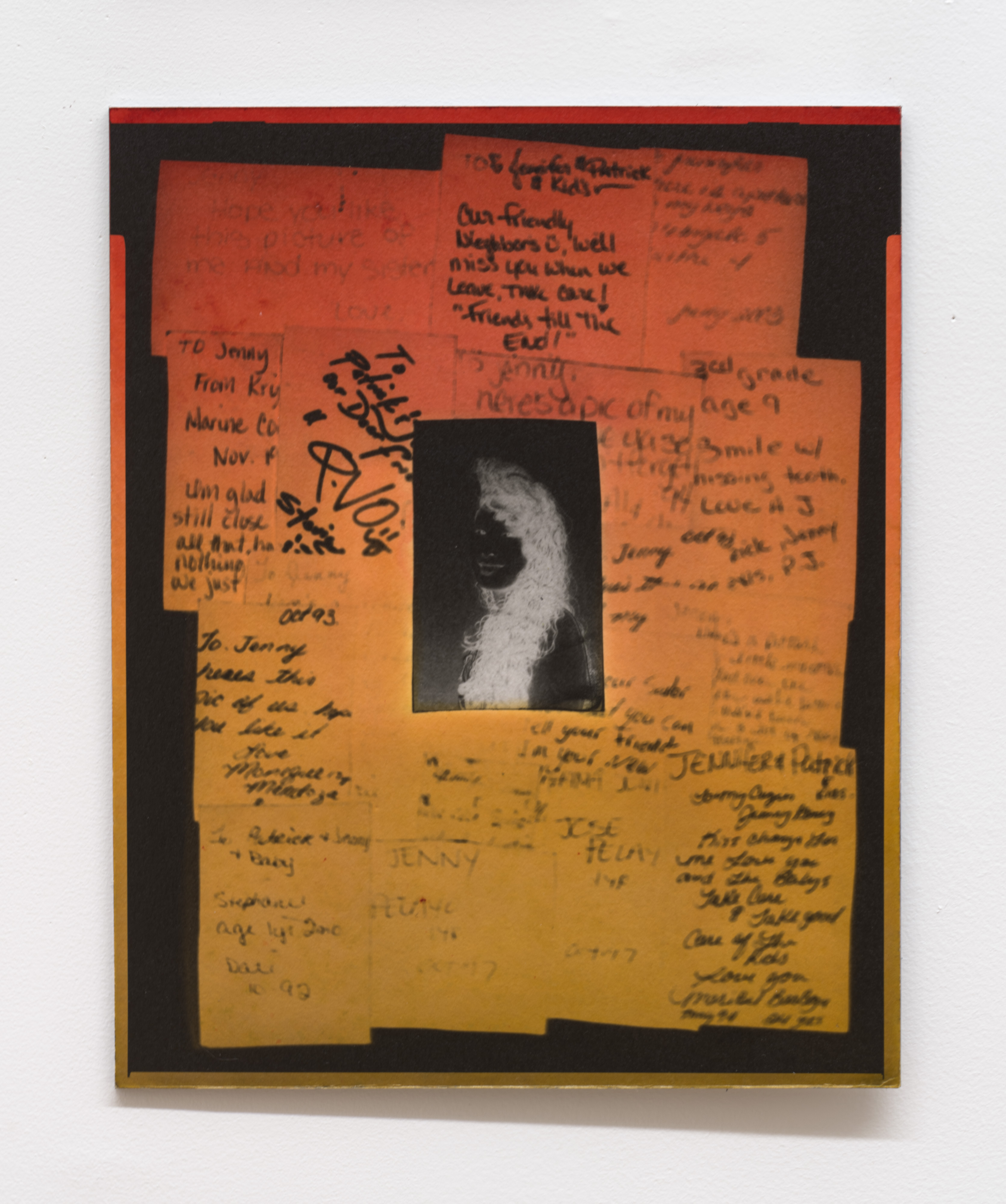

Even though most of us probably don’t know the individual subjects who appear in the show (mostly the artists’ family members), the forms of image-making are so familiar that we seem to recognize these people anyway. Pat Garcia’s “Wallet Sized (To Jenny),” for example, is a collage of notes in different hands, all addressed to “Jenny,” overlayed with an image of a young woman with a 1980s hairstyle, presumably Jenny. It is evocative of a yearbook, scribbled on by classmates, or a scrapbook, showing the quickly jotted notes on the backs of photos. Issey Goold’s five ambrotypes smudge and obscure the artist’s family members; though the faces are not always clear, the images are clearly old and historical, reminiscent of the photos in history books or those of people long dead.

Pat Garcia, “Wallet Sized (To Jenny)” (2025).

Krista Gay’s collagic installation brings us into the familiar space of a living room, showing photographic norms of posing and domestic display. The most prominent image shown is of a young woman posing for a class photo, though her face is blurred into chunky pixels. There is a very particular pose and background that immediately signals a school photo, professionally taken and probably staged in the cafeteria or gym of a high school. Even though my particular high school photos looked a little different from Gay’s example (my school opted for black off-the-shoulder tops instead of blue, and a red rose instead of yellow), the form is so clear it is impossible to mistake for anything else. There are gestures, colors, and framings that stand in for ideas like coming-of-age, adulthood, maturity, and the end of childhood. I don’t know where these standards originated, but they have grown widespread and remained steadfast over decades, becoming instantly recognizable.

The groupings displayed here remind me of my own Oma’s photo wall in her living room, a patchwork of professional photos of my siblings and me as babies, our graduation photos, my parents when they were young, and seemingly random photos that are neither particularly significant or flattering. Gay presents a similar array: various sizes, various frames; some professional, some amateur; some posed, some candid. I always thought the goal of my Oma’s curation was to capture each of us in as many forms as possible, to have records of each differing stage of our lives, dividing us into our many previous selves while simultaneously uniting us on one wall. This familiar maternal practice is like a kind of scrapbook, one that you ambiently see every day, part of the architecture, using memories as decor.

Vivian Vivas, “Since you left, I’ve invented the afterlife, many times” (2025).

Vivian Vivas, “Since you left, I’ve invented the afterlife, many times” (2025). Vivian Vivas’s contribution shows a translucent image of the artist’s father, visible only in faint outlines. It reminds me of the fallibility of photography. The advent of digital photography and new technologies easily accessible to the quotidian mother or grandfather began an age of everyday archives. Suddenly, people could preserve not just the handful of special occasions deemed worthy enough for a professional photo with subjects typically still, unsmiling, and removed from the fabric of their own lives. Anyone could capture any moment and save it forever—at least, that was the goal. Vivas’s images of her father remind me that photographs are not monuments. I only have a few photos of my parents as children, whatever physical images have survived the span of their lives so far. Many more images surely fell victim to accidents: they were casualties of spilled milk, lost in a move, or misplaced, or they just faded away under fifty years’ worth of light. Today’s digital photography seems more flexible, stored on the cloud or an external hard drive, but is it? Software becomes obsolete almost immediately, and I do not doubt that a day will come when things like iPhone photos are packaged in a new way to become nearly inaccessible. My mother recently started digitizing family videos from when my siblings and I were babies, recorded all on VHS or cassette tapes. This process is neither cheap nor foolproof and may destroy some tapes along the way. Photo technology is an ongoing and neverending race against time and the corporations who change device compatibility to hold our memories hostage for money. Vivas’s work looks like a light-bleached image, irreparably damaged.

Martha Naranjo Sandoval, “Main Entrance” (2017).

Martha Naranjo Sandoval’s work similarly points to what’s gone missing. In three small works, the artist excises and collages old photos, stitching together scenes that at first appear normal and familiar. But after a closer look, faint outlines appear—perhaps objects, perhaps people, perhaps nothing at all. The images have been mended, with the artist paying attention to keeping the final images seamless, as if the change should be invisible, the operation unknown. Of course, this is impossible, and the images reveal themselves to be constructions, even if against their will. I imagine painful memories and desires for things to disappear. The images read as ad hoc editing, an intervention into photo-as-memory. They are both hopeful and sad, seeming to posit: perhaps if we can change the photo, we can change the memory too. Or maybe it’s the other way around: if the memory has changed, so should the photo.

The figures and faces in nearly every work on view are blurred out, if there are any present at all. This does not necessarily make people or places unrecognizable; instead, it places form over content. These are not works of biography, historical research, or faithful reproduction. These are not stories about specific people; instead, they are stories about stories themselves.

Time and Time Again: Fiction, Family, in Photography is open through April 10, 2025, by appointment only. Learn more here.