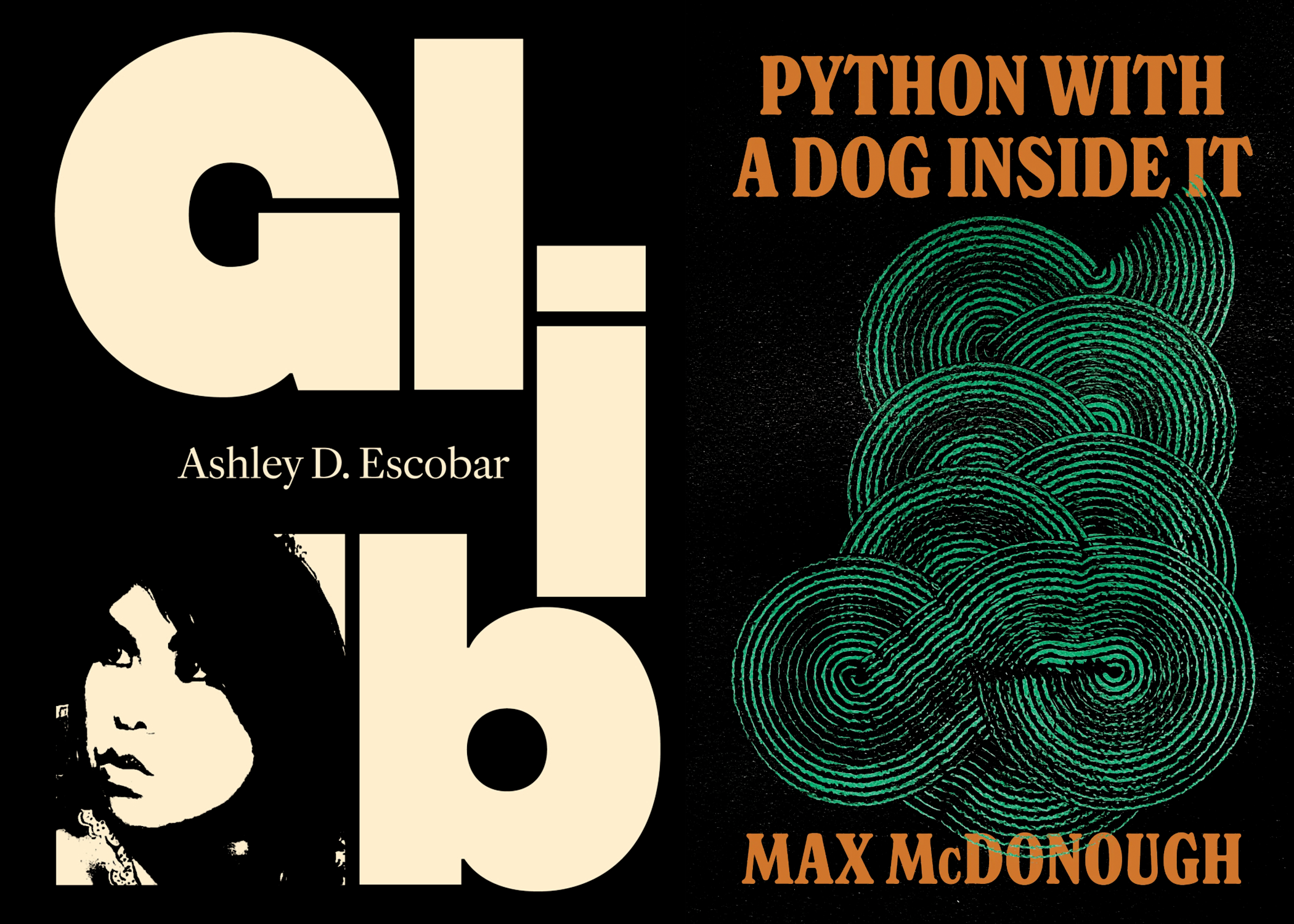

Two New York Indie Presses, Two Thrilling Debut Collections

In Glib by Ashley D. Escobar and Python With a Dog Inside IT by Max McDonough, fresh voices explore intimacy and distance.

By Philip Kenner

5.20.2025

Literature, drama, and music overflow with characters proclaiming exactly who they are. They plant their feet, take a deep breath, and yell to the world: “I am the earth mother,” “I am the walrus,” “I am the bread of life,” and so on. Whether you’re Martha, The Beatles, or Jesus, it is a time-honored artistic tradition to let the audience know who they’re dealing with.

In Ashley D. Escobar’s debut poetry collection, Glib, Escobar positions herself firmly, if mischievously, in this lineage; Escobar’s smattering of speakers proclaim themselves in tilted, incongruous terms, and the poems in this collection dazzle as a result. Chosen by Eileen Myles for the 2024 Changes Book Prize, Glib is a collection of labyrinthian and hedonistic poems that oscillate wildly between vulnerability, obfuscation, and a damn good time.

Escobar’s speakers are multiplicitous; the “I am” statements that sprinkle the collection appear before a panoply of identities. For example, “I am”:

- “a chalkboard”

- “your / secretary”

- “an ongoing diary of a teenage girl”

- “every / matinee of your heart”

Escobar’s “I” traipses through Brooklyn, attends a Q&A after a film screening, and falls asleep next to “you” in a hotel room. These “I am” statements provide both context and provocation, and they ground the book amid a dizzying, delicious litany of intimacies, regrets, and temporalities.

I had the pleasure of reading a majority of these poems on the New York City subway, feeling like I was living the dream of a romantic, kaleidoscopic city life, where beloveds passed in and out of my periphery and childhood memories of grocery store parking lot sunsets give way to hangovers on the R train. Escobar seizes the contradiction between tenderness and total oblivion and turns it into a whispered, flippant joke. In “Vacation Noir,” she writes, “…you / can read the bible but / you’ll never win the war,” and later, “on valentine’s day two plus / two doesn’t equal pink / neither does wearing / sunglasses to the club.” I texted my particularly glamorous, fun-loving friend a picture of the poem and told her she would love it. Love it, she did.

Escobar’s speakers are giving road head one moment, and the next, they’re tenderly admitting to their beloved, “I love being alive with you.” This whiplash between eroticism, humor, and abstraction delivers on the promise of the title. Nothing is serious until it is. Within these pages, you will find glibness, you will feel glibbish, you will surrender to the glibbity of it all.

…

Earlier this spring, another New York State-based indie press, Black Lawrence Press, published Max McDonough’s debut collection, Python with a Dog Inside It. Across the George Washington Bridge from Escobar’s New York City and down the New Jersey Turnpike, McDonough’s poems are set in working-class southern New Jersey. The collection opens with a stunning first poem—“Incunabula as the Light Turns”—that begins, “In the story I keep trying to tell, there’s a woman / handcuffed in the driveway.” This striking image, matched with the speaker’s admission of having tried to tell this story before, is the pitch-perfect introduction for a collection of resolutely emotional yet notably magnanimous poems.

Memories of abuse are told with a slant toward the tender, and when McDonough places us in a scene outside of the courthouse during the speaker’s mother’s trial, the speaker can’t help but notice the “split-open flowers” are “throbbing with pollen.” The speaker remarks how there are “designs hidden” among the bees and hyacinths, and how amid all this, they are “summoned / back to the courtroom… / to testify against her.” These jarring juxtapositions of tenderness and pain are peppered skillfully throughout this powerful debut. For every poem about knuckles covered in scars and withstanding homophobia in a Cheesecake Factory parking lot, there is a poem about how hearing aids help us connect to our aging parents and how you can feel love while flipping through your brother’s medical textbook.

Reading Python felt like having a conversation with that one friend who’s been in therapy for years, and their mature, measured, and generous interpretation of their trauma both impresses and instructs. These poems heal precisely because they are evidence of healing; they are a reminder that the goal of growing up is that when the difficult events of our childhood float into our brain, they engender meaningful contemplation instead of sparking fits of resentment. And before I paint McDonough’s nuanced storytelling with too broad a brush, there is plenty of rage and sadness throbbing beneath these poems.

I was talking with a writer pal about how simple, true sentences are sometimes the most powerful and how it would be in our fellow poets’ best interest to end their poems with a simple, true line. McDonough does this a few times in the book, but most notably in the poem “April Begins in My Father’s Ear.” In this poem about calling their father, the speaker muses on how they can reach their father’s cochlea via a hearing aid, and this reminds the speaker of the tenderness with which their father raised them. In contrast, the poem opens with siblings sleeping beside Target dumpsters and crushing fingers under rocks. Still, in the end, the speaker tells their father, “…You’re / just calling because you’re bored, I hear you say / before you say it, though you answered, though I have your ear, I am in / your ear, we have a tone, it is spring, & you can hear me.” This cascade of grounded, otherwise unremarkable facts becomes proof of life. With a vulnerable, masterful flourish, McDonough reduces the fraction of love over trauma to its prime numbers.

Reading Python, I’m reminded of Adam Clay’s poem “Elegy for a Town Built by Trains”: “I live in a town built / by trains, knowing every / place one day becomes / an elegy for itself.” McDonough presents the working-class, southern Jersey of his childhood through a lens of edifying grief; there is wisdom under pain as there is so often pain under wisdom.

Both collections from indie, NY-based presses are superlative introductions to these fresh, erudite voices. As the weather gets warmer, you can look hot in the park reading some top-notch poetry, and you can support small presses at the same time! These collections are available from the Changes Press and Black Lawrence Press websites:

Glib by Ashley D. Escobar from Changes Press

Python With a Dog Inside It by Max McDonough from Black Lawrence Press

Happy Hot Poet Spring!