![]()

Finding Solace in a Fun House

Reflecting on the power of Nadia Lee Cohen’s haunting Women and finding healing within her cinematic characters

By Cath Spino

All photographs courtesy of IDEA

2.16.2022

Trigger Warning: This article will discuss feelings stemming from body dysmorphia and eating disorders.

Once you know her name and have seen her work, it is almost impossible to forget her. British-born, now-LA resident Nadia Lee Cohen’s work simply cannot be distilled into one intro sentence: it’s truly larger than life. From executing music videos for Kali Uchis and The Garden to shooting the December 2019 cover of Playboy to directing Katy Perry’s “Cozy Little Christmas” holiday home video, her works feature a retro-yet-modern energy full of playful prosthetics, captivating colors, and wild story lines. She’s had a vice grip on me since I first laid eyes on her comical and political “Babushka Boi” music video for A$AP Rocky a couple years back (My top song of 2021 was a ditty she used to score an incredible tracking shot in her short film Sgualdrina that has haunted me since my first viewing last summer).

Nadia gave birth to her first brainchild/volume of work in December 2020, entitled Women. Six years in the making, the golden book showcases 100 portraits of 100 women staged in medias res all through the colorfully cinematic lens Nadia is known for. Nadia clarifies in the book’s foreword that she is using the term “women” as embodying a character. The subjects playing these characters range from Cohen’s personal friends and celebrities to local unknowns she scouted close to their shoots. One common thread throughout all the portraits is nudity; Cohen lets the subject decide how much or how little they’d like to show of their own body in their portrait. Published by IDEA, the first edition of Women reached critical acclaim and quickly sold out, to Nadia’s shock. Critics and art lovers alike were moved by her groundbreaking view on “surreal, sad and sexy photographs… [with] infinite stories [written] across each face and body” (i-D, 2020). Additional pressings were issued, with the (supposedly) last pressing coming out last December. Hearing the words “final pressing” lit a fire under my ass that could only be put out by entering my credit card information on the Dover Street Market checkout page the moment I received an email from the publisher. I even turned on my notifications for emails from IDEA… a big leap for a gal who lives her life on Do Not Disturb.

I had seen bits and pieces of the photographs on Cohen’s Instagram, in her photoshoot for Playboy (which I found for a bargain on eBay), and of course in the occasional Google search of her name when I had nothing going on; I was incredibly shocked when I felt a peculiar shift in energy cracking the spine of the gold fabric hardcover for the first time, a divine knowing that this book was more than just portraits. Holding Nadia’s book, I felt like a kid in the packed costume closet of my community theatre: I turned every page slowly and with care, as if I was waiting for one of her portraits to come alive. Like i-D mentioned, all of these portraits were drenched in cinematic narratives and I didn’t want to miss a detail. As my fingers eagerly turned each page, careful not to leave fingerprints, I began to see less of the women photographed and more of myself.

For a good chunk of my life, I’ve struggled processing my womanhood and my changing body. I hit puberty in the mid 2000s: the age of low rise denim, stick thin models with huge tits, Girls Gone Wild, Cosmopolitan headlines on how to keep your man happy (one I vividly remember involved using honey during a blow job). When I’d finger through Teen People or Teen Vogue, I was keenly aware I was not one of these skinny girls. I was not athletic and was on the larger size of kids in my classes. And back then, the diversity of models and celebrities was almost nonexistent compared to the 2020s.

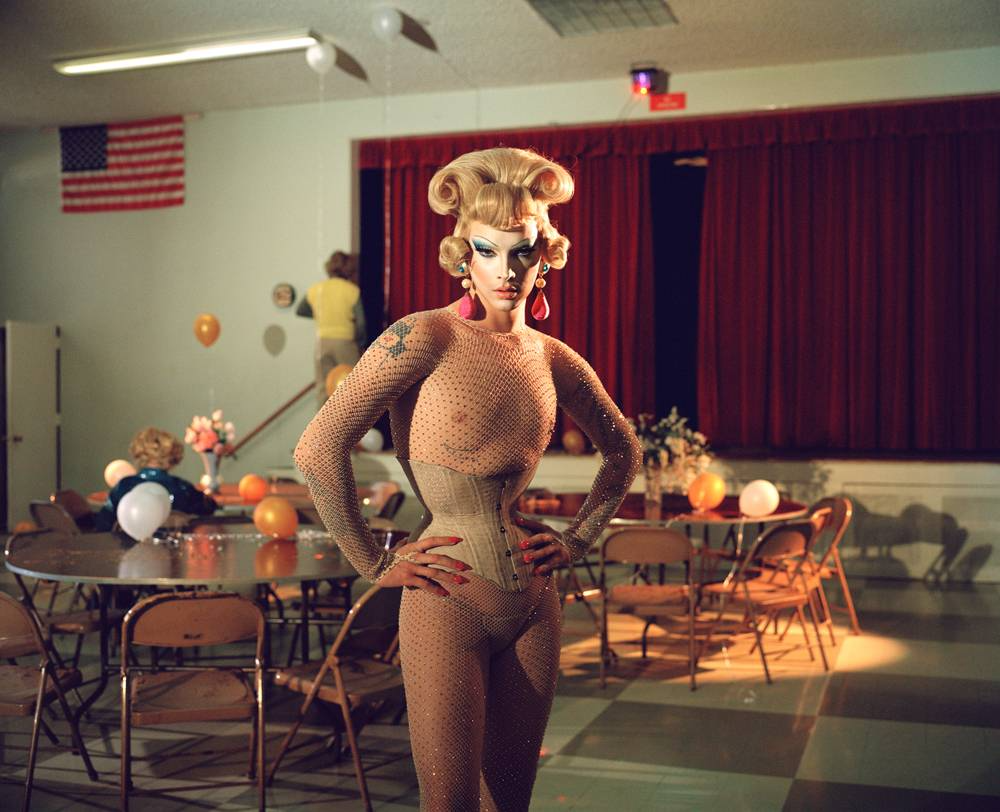

“Mickey, Downtown, Los Angeles”

Internalizing these feelings of being socially undesirable to men, I tried to make myself more desirable in ways I could control. I have fair skin and dark hair, so I started waxing my upper lip in 5th grade after I heard a boy make a comment about another girl’s upper lip hair making her “look like Hitler.” Shortly after that, I started shaving my legs. I remember consistently being called “Chewbacca” in middle school because of my hairy arms, but my mom refused to let me shave them, stating that once you start, you can really never stop. I remember sobbing on the phone to my mother after my brother found my used tampon in the toilet and wouldn’t stop making fun of me for simply having a period and therefore, being a healthy woman. I remember calling my best friend in high school for grooming advice as I painstakingly shaved my pubic hair for the first time because my first boyfriend demanded it. I remember a girl in my freshman class in college telling me my hips were “uneven” when I was adjusting a thong in a cotton spandex-blend mini skirt from Urban Outfitters before we went to a party. I never had an eating disorder but I acknowledge that I’ve had a disorderly relationship with eating: eating a salad on Friday and Saturday nights for dinner so I could look smaller at parties and in any photos that people took of me that would be posted to Facebook and, later on, Instagram. I ordered American Apparel bodysuits a size smaller than my normal size as an incentive to work out more but instead, I found they made my tits look better and men did double takes when I entered rooms. “Becoming a woman” for me was an understanding that I was constantly a visual subject and it became my job to make society comfortable with my presence.

“Violet, Hollywood, California”

“Flo, Bethnal Green, London”

If I looked too long at my naked form, I slowly found myself comparing it against the models and porn stars of my youth and the popular girls in school: the stick-thin women with seemingly perfect perky breasts in low rider jeans or string bikinis. I would suck my abs so far back that I couldn’t breathe as I questioned why I ate what I ate the day before. I would twist my body around so my stomach looked smaller and arch my spine so my ass looked bigger. I would imagine my upper arms slimmer without my keratosis pilaris red bumps, my bikini line hairless and my gut nonexistent. I would slowly see less of who I was and instead see who society told me I wanted to be: a version more digestible and expected for future lovers.

“Brooke, East Hollywood, California”

Looking at Nadia Lee Cohen’s portraits, I see so many different kinds of bodies. Bodies that have lived full lives, bodies that have carried their owners through dark nights and sunny days. Violet Chachki’s striking corseted waist, Mickey’s determined aged arms pushing her groceries, Brooke’s steely gaze and breasts covered in tattoos. There is no airbrush, no perfect breasts, no perfect ass: these are photographs of women through a female gaze. My first experiences seeing naked women were images clearly satisfying the male gaze: women in porn or paintings of nude females lying in repose by male artists during my art history courses in college. Nadia’s women aren’t submissive. Whether they are in repose breast feeding their baby, vacuuming a carpet or even refusing to meet your gaze lighting their cigarette, they are doing it on their own terms and not for your pleasure. And as I devoured each and every page of Nadia’s book, I became more aware of my womanhood. The way my left breast is bigger than my right (a telltale sign that there’s a beating heart under the muscle), the way my stomach naturally pouches above my pubic bone, the curvature of my hips, the way my stomach rolls when I’m seated, the shape of my calves, the weird “not too long, not too short” length of my pubic hair. I felt seen in my body and everything made sense again.

“Shocking, Hackney, East London”

In her forward, Nadia mentions that she uses the term “women” as an idea relating to character. I read her foreword after flipping through the book a couple times over and was struck by that logic because at the core of my experience of being a woman, I was first and foremost a caricature of myself. I knew the old song and dance: how to bat my eyes and suck in my stomach to get a male’s attention, how to make my smile broader and my laugh quieter. I found it easier to be a character that knows how to please its audience first. In a world that was not always accepting (and still isn’t always accepting) of all the facets of self expression, being a character was an act of survival. But what shocked me the most about these portraits was how much I cared about them. I wanted to hear their stories, I wanted to see how they lived their lives, I wanted to know the outcome of the pageant, if they were able to find all the groceries off their list. I wanted to see who their eyes were looking at off camera.

“Scarlett, Hampstead North London”

I grew up outside of Boston, so I took many trips to the Museum of Fine Arts. Even though I’d wander aimlessly, during every visit I’d find myself in the Greek wing amongst the statues of mythological warriors and leaders. And despite feeling this pressure to look like a queen of Y2K fashion, I remember always idolizing the Greek female statues. These glorious, strong, powerfully full-bodied women who had stories anchored in destiny of where they came from and where they were going. I think of these statues as I look at Nadia’s Women: figures of powerful women whose stories I desperately want to hear. But more importantly, these figures have empowered me to listen closely to my own stories, stories I have longed to trust as a sign of strength and believe my whole life, leading me to a place of healing and acceptance I could have never imagined.

You can find more of Nadia’s work on her site and follow her on Instagram. Her second photography book Hello My Name Is is currently sold out but you can sign up for notifications once it’s in stock here.