![]()

I Love You,

Farrah Abraham

The reality TV star has meant so much to those of us whose work has been declared unserious and untrained.

By rebecca loftin

2.16.2022

“I can only put so much in this song,” Farrah Abraham begins, her synthetic voice warbling through the track. So will I, here: I can only put so much in this song. For years, I have loved Farrah Abraham, rambling to patient men in bars about her seminal album, My Teenage Dream Ended, and its influence on the hyperpop music genre. They nod, not quite grasping anything I’m saying, and change the subject.

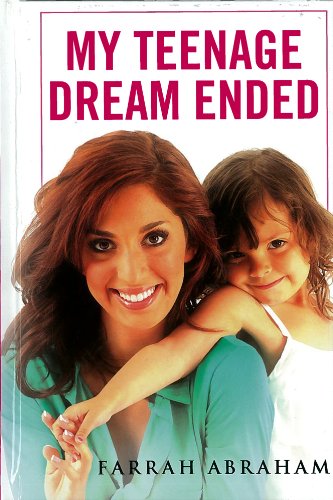

Abraham, now thirty, got her start on MTV’s 16 and Pregnant and the Teen Mom franchise. For those who don’t remember, the documentary series followed small-town, usually middle-class teenage girls balancing family, relationships, high school, and, yes, motherhood. In 2012, Abraham released an autobiography and accompanying album both called My Teenage Dream Ended.

Despite the book’s run as a New York Times Bestseller, people mocked the album for its jarring soundscape and auto-tuned vocals. They passed off Abraham herself as cringe-worthy and amateurish. The album is not for everybody: her disquieting, synthetic wail against the screeching, maximalist percussion is a lot. It’s avant-garde and futuristic, reminiscent of early Bjork. If the cover featured artwork by Petra Collins instead of a cheesy 80’s-style photo of Abraham and her daughter, or if a reality star hadn’t made the album at all, it would have been recognized as such.

After an onslaught of mocking reviews (many have since been deleted), highbrow publications put out reaction reviews, most notably io9, The Fader, and The Atlantic, writing of the “sneaky” and “misunderstood” genius of Abraham and the album’s emotional darkness. These writers, all cisgender white men, praise her work with an air of clickbait surprise. In his Atlantic piece, David Cooper Moore asks us to listen to Abraham’s work “as a piece of art, and a compelling story emerges. Seriously.”

Following on the heels of better, less bro-y publications, Vice released a piece entitled “Is Farrah Abraham the Last Outsider Artist?” The article’s author acknowledges the album’s artistry, but his skepticism and misogynistic disdain for Abraham undermines any praise for her talent. He calls her “America’s current favorite Whore of Babylon.” It is not the only time he uses such language, also writing, “I would dismiss [her] as another famewhore who sucks at lying, but in 2012 she released a critically acclaimed noise album, My Teenage Dream Ended.” Without the album’s clout, these men would in all likelihood write off Abraham as an object of ridicule.

In all fairness, it was the 2010s and reality TV stars were not taken so seriously. But is it so hard to believe that someone with a varied and tragic personal history, much of it documented on national television, could create anything so ground-breaking, so brilliant? My Teenage Dream Ended remains, nearly a decade later, a cutting portrait of female teenage angst and the effects of trauma. Produced from click tracks, stream of consciousness lyrics, and distorted vocals, the album is staggeringly different. Her first foray into the music world transformed from a hotspot of ire into a darling of avant-garde music. Just look at Track 7, “Searching For Closure”:

I see your friends, family, and all those in between

I hate how they've acted

Disrespect, lies, a big mess

Lack of love

You deserve better—I'm only trying to make the difference

I'm holding back my tears, my tongue

This kills me

After starring in the adult film Farrah Superstar: Backdoor Teen Mom and its follow up, Farrah 2: Backdoor and More, she signed a contract with The Palazio Gentlemen's Club in Austin, Texas for over half a million dollars. I used to drive by its fake, Olive Garden-esque Roman architecture on my way to piano recitals just before Farrah’s residency in 2015. You could see the structure from the highway, roughly a hundred feet from a Walmart. From this alone, I know that whatever privileges Farrah Abraham might have gained in her lifetime have not been by chance.

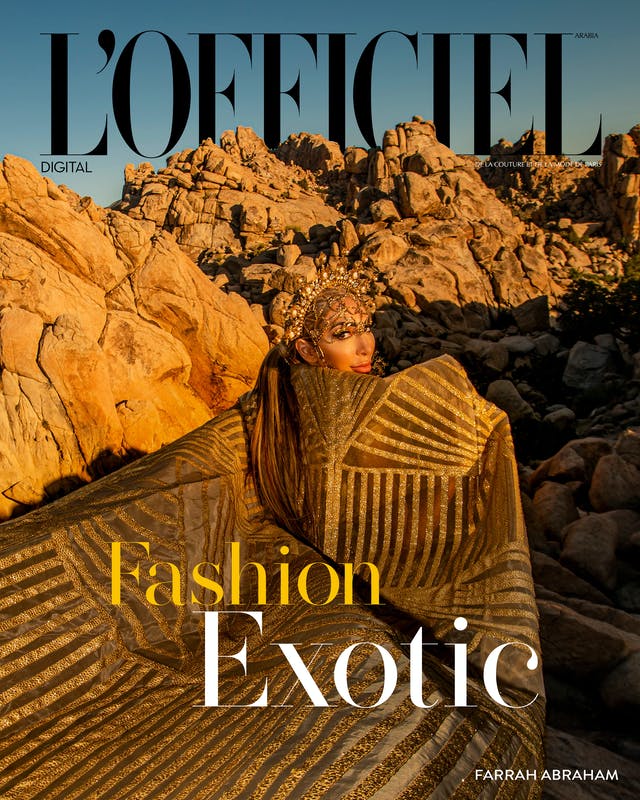

She now graces the covers of fashion magazines (most recently L’Officiel Arabia) and attends philanthropic events with Hollywood insiders. She and her twelve-year-old daughter, Sophia, seem to be doing well. She primarily posts Instagram Reels and YouTube videos, many of which have an activist slant with long, earnest captions. An October 15th Instagram post reads, “I had to support WOMAN FIGHTING FOR THEIR FUNCTIONALITY (lives)& Sharing an incredible journey- I know we may have our struggles with health this past two years, and this was a great reminder - YOUR STRONGER THEN SOMEONE TELLING YOU ‘IT’S ALL IN YOUR HEAD.’”

Despite having over three million Instagram followers, she has remained an outsider. People have strong (usually negative) opinions on Abraham, often in regards to her sex work, lack of formal education, willingness to monetize her public persona, or for no reason at all. I read the comments on a pinned YouTube video of Abraham talking about abortion and women’s rights. In the words of a particularly nasty one: “We all know about your yachting stories. Having sex for money. I really hope you don’t drag your daughter around with you when you perform.” She cited her sex work as the main reason for her removal from the Teen Mom franchise, which Viacom, MTV’s parent company, denied in a lawsuit settled out of court.

With Abraham, there seems to be no end of controversy. With a constant churn of tabloid blurbs in Us Weekly and People, her life is now conspicuously absent from those highbrow publications that praised her work back in 2012. Still, she shines against her backstory, which is unendingly updated for the worse. Earlier this year, she accused former Windsor, California mayor Dominic Foppoli of sexual assault, becoming one of nine women who accused him of similar crimes. And her mother, Debra Danielsen (rap moniker: Debz OG), who was previously charged with assault towards Abraham in 2010, has been recently accused of elder abuse by Danielsen’s mother.

The few of my circle who know Farrah know her as I do. They have listened to My Teenage Dream Ended hundreds of times and, like me, have feverishly sent their friends “On My Own,” begging them to give her a chance. The album served as a linchpin for the absurdist, emotional soundscape of 2020s electronic pop music (SOPHIE, 100 Gecs, and Charli XCX come to mind). A Pitchfork review of Charli XCX’s Pop 2 even drew explicit comparisons to the Teen Mom star, arguing outsider art inspired the soon-to-be insiders. Beyond a first listen, Abraham’s diaristic, stream-of-consciousness lyrics emerge. The last bit of the opening track, “The Phone Call That Changed My Life,” stands out:

I still had so many other days planned for you

I still look forward to talking to you

I still pictured us together

Yeah, the whole "You and I forever"

The song was inspired by her late boyfriend, Derek Underwood, who died less than two months before the birth of their daughter. In December of last year, she posted a slideshow tribute for Derek. A flurry of photos of Sophia, Derek, and a very young Abraham flash by. “12 YEARS LATER. Sharing these words and clip from over the last 12 years, as others may feel depressed, hurt, overwhelmed this holiday- I hope you know you are strong,” she writes.

Even with much-deserved credit from retrospective music criticism, her total streams on Spotify are barely more than what Matthew Lee Cothran has for a single he dedicated to her, called, aptly, “Farrah Abraham.”

Farrah sings to see dead dreams come alive

In another life, maybe I'd have been your child

If I could end the world, I would end the world

And when I think about the charge of domestic abuse against Abraham’s mother, who forcibly prevented her daughter from getting an abortion and, as a police report reads, "hit [Abraham] along the side of her head and hit her in the mouth," I think that in another life, as Matthew Lee Cothran might have been Farrah’s child, I might have been her.

Both victims of domestic abuse, she and I shared similarly chaotic upbringings and were unable to cleave from our abusers until well into adulthood. But unlike Abraham, I grew up with a second parent, both loving and financially independent, a tangible “out” from hellish home life. Abraham and her mother initially went on 16 and Pregnant to ease the expenses of imminent motherhood. Regardless of the tumult of my childhood, I never wanted for resources that would later be necessary to break from my family.

No matter how you spin it, childhood trauma and abuse irrevocably alter a person’s mind. But when we talk about resiliency and the politics of tragedy, we leave money out of the equation. We inspire the masses with tales of overcoming great personal struggles but not the privileges or fickle power of chance that turned the tide. Money, race, and state programs cannot be extricated from that aspirational trait we call resiliency. Farrah Abraham and I remain products of our circumstances for good and for ill.

I cannot stress how much she has meant to me, to so many of us who felt like outsiders, whose work has been declared unserious and untrained, and who have been discouraged from pursuing the things they love because of it. I think of the closing track on the album, “Finally Getting Up From Rock Bottom.”

Heavy traffic on the highway

My eyes are up, up, up

My head's on Thursday

Look back, past is gone

From back underneath the day

My heart breaks for all the public did not, and still refuses to, acknowledge. When I think of Farrah Abraham, I think of Anna Nicole Smith, Vanessa Williams, Britney Spears, and Tonya Harding: women we painted as trashy for lower-class origins, a willingness to cash in on their sexuality, or their outright refusal to do so. And I wonder how little credit we are willing to give to women like Farrah Abraham. In another life, her path might have looked something like mine. She might have gone to a state school, became a writer of sorts, moved on and up, ordinary and happy. In another life, she might have been a poet.

Listen to My Teenage Dream Ended