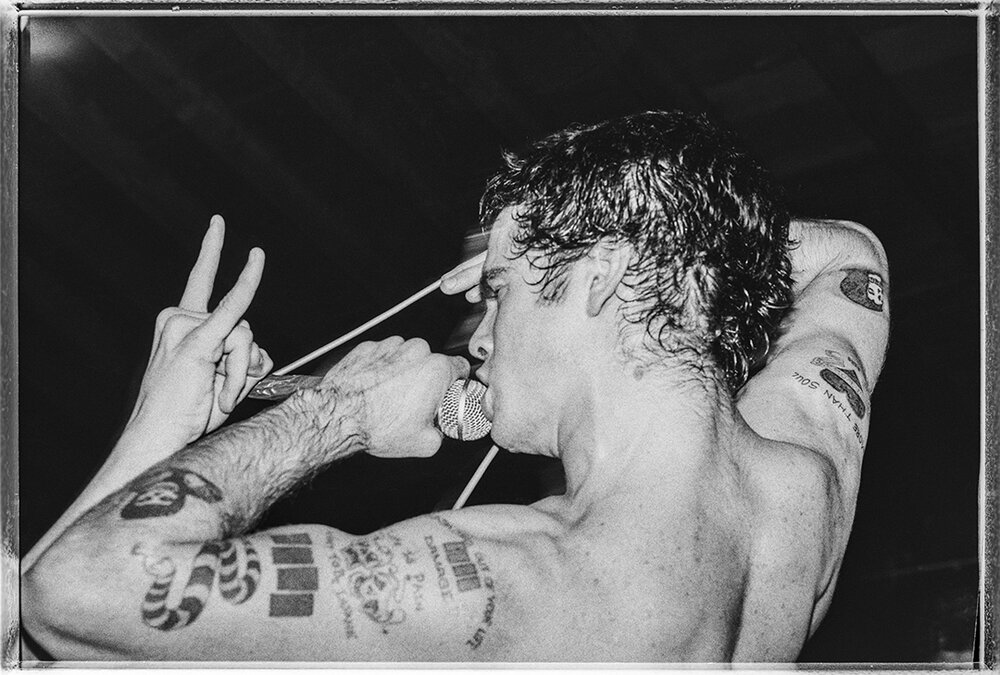

“Black Flag Photo #1” by Kevin Salk (Fathom Gallery)

“Black Flag Photo #1” by Kevin Salk (Fathom Gallery)Kevin Salk’s Serendipitous Punk Rock Photography

As a kid with a camera, Kevin salk captured southern california’s iconic punk rockers.

By Taylor stout

12.22.2021

I have mixed feelings about my hometown of Manhattan Beach, California. As idyllic as it was, I felt out of place in it. I looked to art—music, movies, anything—for a sense of community.

Photographer Kevin Salk grew up in Manhattan Beach and attended my alma mater of Mira Costa High School a few decades before me, in the early 1980s. While Salk still resides in Manhattan Beach, the place sowed seeds of alienation and anger while he was a teenager. As isolating as these emotions may be, Salk wasn’t alone in them. The South Bay’s punk scene—home to bands like Black Flag, Circle Jerks, and Descendents—was flourishing around him. It was violence. It was noise. It was community.

During his years at Mira Costa, Salk was a firsthand witness to this transformative music scene. He attended a handful of shows around Southern California and captured a few hundred photos of the bands he loved. After graduating in 1983, Salk put his photos in storage and left South Bay punk behind.

But his stark black-and-white snapshots wouldn’t collect dust forever. In September of 2021, Salk published a book of his photos called Punk: Photos From a Fan’s Perspective. Shortly after the book’s publication, I caught up with Salk to talk about music, photography, and our shared hometown.

KS: The seeds to sow the anger and alienation of punk rock started as a kid in Manhattan Beach. I came from a Jewish family with divorced parents. In junior high school I went through an Elvis Costello phase, then started listening to the Clash, and then things progressed into punk rock. It was like being part of a group that was not part of a group. It irritated my parents, which was an added benefit. The shows were insane. There were fights like I’d never seen before. There was violence that was involved with the music—that was very intriguing. It fit my mindset and where I was at the time in 1981. One of my friends I’d known since kindergarten had started going to shows before me and I sort of followed him into the gigs. I loved the speed, the lack of authority, and that the music bothered people. Black Flag was the center of my universe.

TS: i imagine it was freeing to find space for that anger when you were in an environment that felt discordant with it.

KS: It was scary. At Mira Costa [High School], jocks did not like punks. There were maybe six or seven of us. That included a brother and sister who were older than us and got into the punk scene in the late 70s, but even they didn’t like us. We had our little crew. I was always respectful to teachers. I never got suspended, I got decent grades, and I never was a problem in class—I was too shy. I never wanted to stand out too much. I was a punk when I got home from school. I still had the look, but I didn’t wear motorcycle boots to school. But I was going to shows a couple times a week, I was going to some really scary places and seeing the music and the environment that I loved. But I was not someone who was in the middle of the slam pit or part of the fights, I just had friends who were who protected me.

TS: What inspired you to start photographing these shows? Was photography something you had done before?

KS: No, I hadn’t done it before. There were two photographers I knew of at the time: Glen Friedman, who was New York-based, and Ed Colver, who was in Los Angeles. They had photos published in some punk rock zines. So maybe I wanted to be in a magazine, but I can’t really put a finger on it. In 1982, I started bringing a point-and-shoot camera, but I can’t really tell you why—I just did. I got my film developed at a drugstore. Eventually, I graduated to a real camera. The first show I went to was Black Flag at Ukrainian Hall, maybe December of 1982. I started to take some better pictures. I took a photography class at Mira Costa. I built a darkroom in my bathroom and that’s where I learned how to develop film. Maybe it was a way to show my photos to my friends and give them xeroxed copies to feed my fragile ego. It was a way to bring myself value. Being a Jewish kid in a Christian town back then was very difficult for me. Christmas night was probably one of the most depressing nights of the year. I think that was a big part of it—you feel alienated and you want to rebel against society. I wanted to rebel against Manhattan Beach and my parents, but I was still scared. I wasn’t the one that would participate in riots, but I sure saw some. The camera allowed me to get close to bands. I was able to befriend the guys from Black Flag. It made me feel important.

KS: There was no objective. I think my only mission was getting on stage and getting access. I wish I could give you a better answer. It just was.

KS: It’s very different now. I went and shot some photos of Pennywise and Descendents. One difference is the new camera technology. Back in the 1980s, it was a camera, a flash, and film. Nowadays, there’s a little more structure because you have the photo pit that you get special access to, which is great. It was cool to get that access—maybe I’ve developed some credibility. I’m going to see Bad Religion next month and there won’t be a photo pit, so I’m going to try and shoot photos the old-school way, which is to get in there and use people to hoist me up. Back then, I think one thing the camera did was give me protection from the really violent people. I never saw a photographer get his head kicked in.

![“Misfits Photo #5” by Kevin Salk, ℅ Fathom Gallery]()

“Misfits Photo #5” by Kevin Salk (Fathom Gallery)

KS: I’m 56 now, so there’s that. I haven’t shot in the crowd yet, but I’m looking forward to it because you do get your adrenaline going. People look at you differently because you’re capturing something. The pit is tame now compared to what it used to be. It used to just be the stage and you were right up on the stage. There was no safety net or barrier. Maybe that was part of the thrill. It’s a very different experience, even if the music carries the same energy. What Pennywise is doing now is just great. I’ve known them since junior high school, and with the way they’re playing now, it would’ve been just full-scale riots and insanity back in the 80s. I’m looking forward to going into a pit. I think I’ll be able to hold my own pretty well, even at the age of 56.

KS: One of the biggest treasures that I’ve gotten from this is having my dad be proud of me. My mom passed away about 15 years ago, but I know she’s proud of me. There are things I put my mom and dad through that I can never forgive myself for, and to have my father proud of me, that’s everything. So I think if my teenage self could view me now, I would think I’m pretty damn cool.

TS: After this period of attending shows, did you keep taking pictures, or was it something that was unique to that moment?

KS: I graduated from Mira Costa in May of 1983 and went to college. I still went to shows during that summer, but starting September of 1983 I was in college and put everything in storage. I began fraternity life. I was drinking heavily and not studying very much. I left the punk rock scene almost entirely until seeing Pennywise in 2011. I put everything away, literally put it in a storage box, for over 30 years.

KS: I felt like a deer in headlights because of the professionals there. I think I missed a lot of shots because of the camera settings. But it was fun. You shoot 1000 pictures on digital to find 10. Back in high school, I took a picture of Keith Morris with a shoe in his mouth at the Goleta Community Center on January 21, 1983. It’s the best picture of Keith Morris ever taken in my very humble opinion. It’s a lifetime money shot. It was fun to go through and find the one photo that stands out. What I’m trying to do now is use technology to make the photos look like they’re on film. Anything that I put on the web or my Instagram is going to be black-and-white. My photos back then were imperfectly perfect. With today’s work, I’m doing it because it’s fun and it’s kind of cool to get back into shooting. But everyone else is doing the same thing and there are people who are a hell of a lot better at it. With the photos from back then, there’s a romance to them. There’s also a scarcity to them. There were not many people who took photos back then.

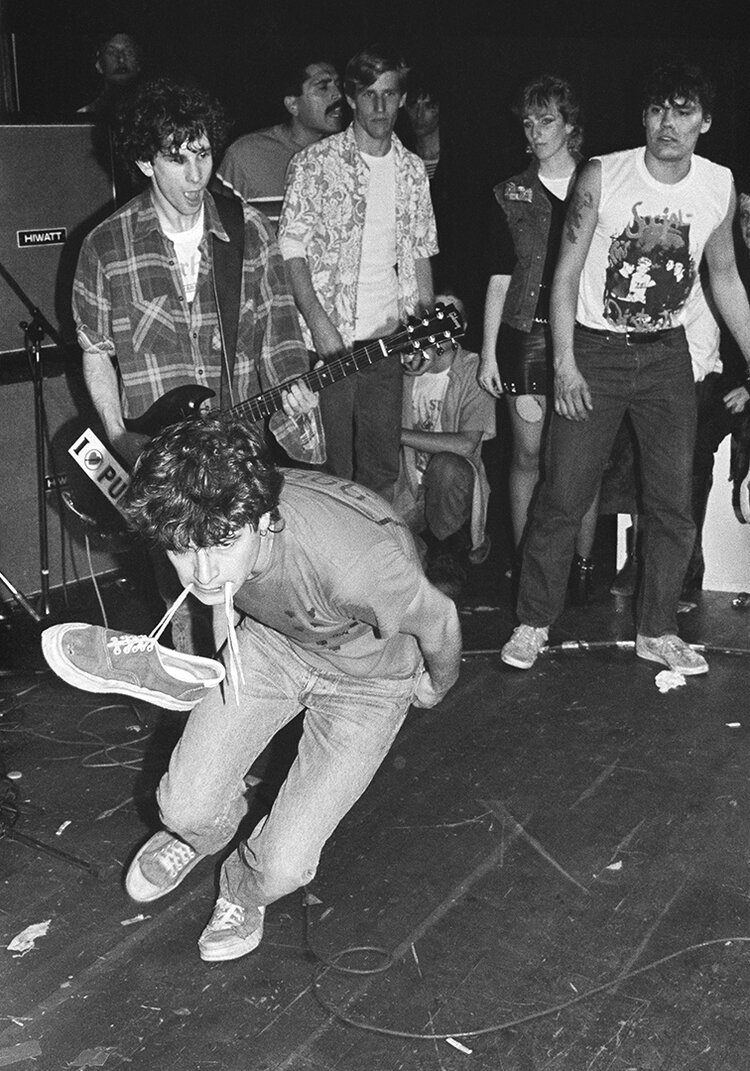

![]() “Circle Jerks Photo #2” by Kevin Salk (Fathom Gallery)

“Circle Jerks Photo #2” by Kevin Salk (Fathom Gallery)

TS: It was this distinct moment that came and went, and you were there to capture it.

KS: It’s overwhelming to be recognized for that. It really freaks me out. But as my daughter said, I’ve been able to find my authentic self. It took a lot of pain and suffering. This has allowed me to go back in time, review that time, pick the parts that are important and delete the parts that aren’t. It’s not just the photos. It’s been a spiritual journey and a life journey. I look in the mirror and I like what I see now. July 22, 2019 changed my life. I was sitting in my office and I got a text from Frank at Fathom Gallery saying, “I saw your work on the internet and I’d like to talk to you.” My reaction was, “What time?” I think I met with him that afternoon or the next day and I signed a contract the day after. I had two photos in a punk rock photography exhibit at Fathom Gallery and everything went hypersonic from there. I was going to have my own photography exhibit right before COVID, my own show in a gallery, to then have my book published. That moment changed everything.

TS: So You’ve been following that path since then?

KS: I’ve been enjoying the path. There’s still a lot of things that are normal. I’m a cyclist, I have daughters, and my girlfriend’s a PhD in Art History. She published a book and she’s working on her next book. I’m in the finance business and I’d rather spend an evening with artists and hear the story of their art than sit and talk to someone who runs a hedge fund. That’s boring.

TS: I share that sentiment.

KS: The art and the people behind it is what’s interesting. It’s been so great to share that with my girlfriend and kids. I have a lot of suits and ties sitting in my closet that I’m probably not going to wear ever again. Part of it’s because of COVID, but also because they don’t represent who I am anymore.

KS: In the morning, I listen to classical music. I really like Vivaldi. But my music ranges from Black Flag to Metallica to Pennywise to Slipknot to Gobsmack to Iron Maiden to Circle Jerks to Misfits. I like music that is fast and loud. I love Slipknot. I also love jazz. Classical and jazz calm my soul. I listen to bands now that I didn’t listen to a lot before, like Social Distortion. I’m still evolving.

Photographer Kevin Salk grew up in Manhattan Beach and attended my alma mater of Mira Costa High School a few decades before me, in the early 1980s. While Salk still resides in Manhattan Beach, the place sowed seeds of alienation and anger while he was a teenager. As isolating as these emotions may be, Salk wasn’t alone in them. The South Bay’s punk scene—home to bands like Black Flag, Circle Jerks, and Descendents—was flourishing around him. It was violence. It was noise. It was community.

During his years at Mira Costa, Salk was a firsthand witness to this transformative music scene. He attended a handful of shows around Southern California and captured a few hundred photos of the bands he loved. After graduating in 1983, Salk put his photos in storage and left South Bay punk behind.

But his stark black-and-white snapshots wouldn’t collect dust forever. In September of 2021, Salk published a book of his photos called Punk: Photos From a Fan’s Perspective. Shortly after the book’s publication, I caught up with Salk to talk about music, photography, and our shared hometown.

TS: Tell me a little about how you found the South Bay punk scene when you were a teenager. What people or events led you to these shows?

KS: The seeds to sow the anger and alienation of punk rock started as a kid in Manhattan Beach. I came from a Jewish family with divorced parents. In junior high school I went through an Elvis Costello phase, then started listening to the Clash, and then things progressed into punk rock. It was like being part of a group that was not part of a group. It irritated my parents, which was an added benefit. The shows were insane. There were fights like I’d never seen before. There was violence that was involved with the music—that was very intriguing. It fit my mindset and where I was at the time in 1981. One of my friends I’d known since kindergarten had started going to shows before me and I sort of followed him into the gigs. I loved the speed, the lack of authority, and that the music bothered people. Black Flag was the center of my universe.

TS: i imagine it was freeing to find space for that anger when you were in an environment that felt discordant with it.

KS: It was scary. At Mira Costa [High School], jocks did not like punks. There were maybe six or seven of us. That included a brother and sister who were older than us and got into the punk scene in the late 70s, but even they didn’t like us. We had our little crew. I was always respectful to teachers. I never got suspended, I got decent grades, and I never was a problem in class—I was too shy. I never wanted to stand out too much. I was a punk when I got home from school. I still had the look, but I didn’t wear motorcycle boots to school. But I was going to shows a couple times a week, I was going to some really scary places and seeing the music and the environment that I loved. But I was not someone who was in the middle of the slam pit or part of the fights, I just had friends who were who protected me.TS: What inspired you to start photographing these shows? Was photography something you had done before?

KS: No, I hadn’t done it before. There were two photographers I knew of at the time: Glen Friedman, who was New York-based, and Ed Colver, who was in Los Angeles. They had photos published in some punk rock zines. So maybe I wanted to be in a magazine, but I can’t really put a finger on it. In 1982, I started bringing a point-and-shoot camera, but I can’t really tell you why—I just did. I got my film developed at a drugstore. Eventually, I graduated to a real camera. The first show I went to was Black Flag at Ukrainian Hall, maybe December of 1982. I started to take some better pictures. I took a photography class at Mira Costa. I built a darkroom in my bathroom and that’s where I learned how to develop film. Maybe it was a way to show my photos to my friends and give them xeroxed copies to feed my fragile ego. It was a way to bring myself value. Being a Jewish kid in a Christian town back then was very difficult for me. Christmas night was probably one of the most depressing nights of the year. I think that was a big part of it—you feel alienated and you want to rebel against society. I wanted to rebel against Manhattan Beach and my parents, but I was still scared. I wasn’t the one that would participate in riots, but I sure saw some. The camera allowed me to get close to bands. I was able to befriend the guys from Black Flag. It made me feel important.

TS: What did you want to capture about these bands that you loved?

KS: There was no objective. I think my only mission was getting on stage and getting access. I wish I could give you a better answer. It just was.

TS: That’s its own kind of method. It’s thrilling to be part of this big experience that’s happening.

KS: It’s very different now. I went and shot some photos of Pennywise and Descendents. One difference is the new camera technology. Back in the 1980s, it was a camera, a flash, and film. Nowadays, there’s a little more structure because you have the photo pit that you get special access to, which is great. It was cool to get that access—maybe I’ve developed some credibility. I’m going to see Bad Religion next month and there won’t be a photo pit, so I’m going to try and shoot photos the old-school way, which is to get in there and use people to hoist me up. Back then, I think one thing the camera did was give me protection from the really violent people. I never saw a photographer get his head kicked in.

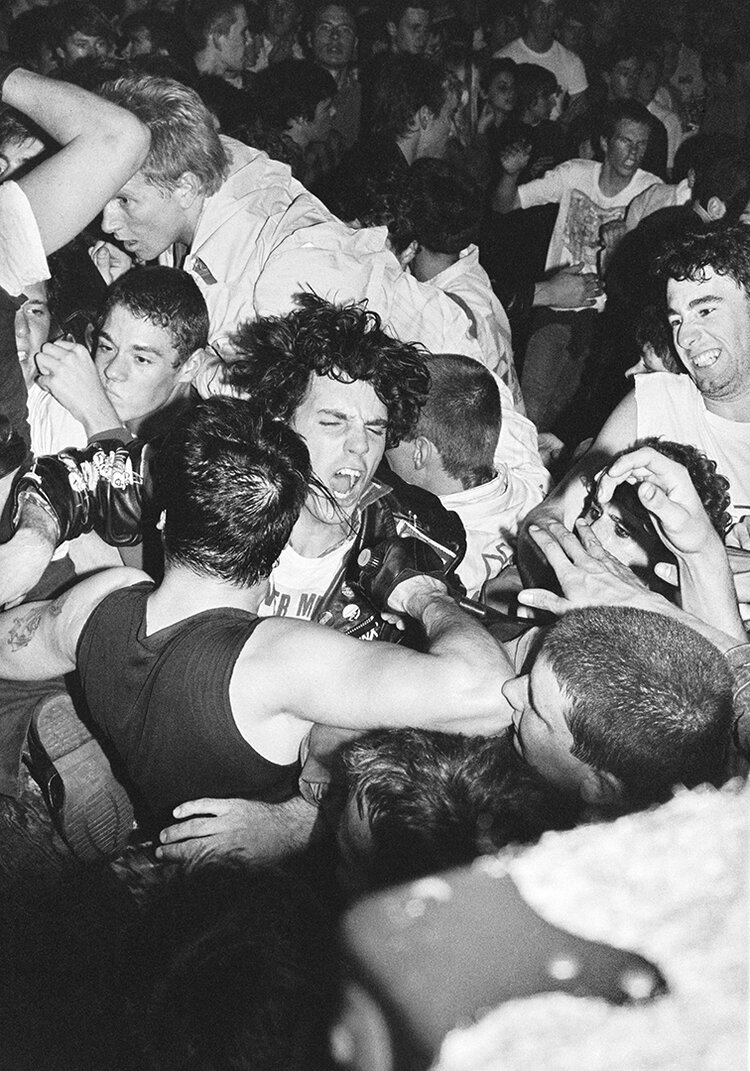

“Misfits Photo #5” by Kevin Salk (Fathom Gallery)

TS: Do you prefer the old-school way of being in the crowd and being hoisted up or do you prefer the photo pit?

KS: I’m 56 now, so there’s that. I haven’t shot in the crowd yet, but I’m looking forward to it because you do get your adrenaline going. People look at you differently because you’re capturing something. The pit is tame now compared to what it used to be. It used to just be the stage and you were right up on the stage. There was no safety net or barrier. Maybe that was part of the thrill. It’s a very different experience, even if the music carries the same energy. What Pennywise is doing now is just great. I’ve known them since junior high school, and with the way they’re playing now, it would’ve been just full-scale riots and insanity back in the 80s. I’m looking forward to going into a pit. I think I’ll be able to hold my own pretty well, even at the age of 56.

TS: How do you think your teenage self would feel about you publishing a book of these photos?

KS: One of the biggest treasures that I’ve gotten from this is having my dad be proud of me. My mom passed away about 15 years ago, but I know she’s proud of me. There are things I put my mom and dad through that I can never forgive myself for, and to have my father proud of me, that’s everything. So I think if my teenage self could view me now, I would think I’m pretty damn cool.

TS: After this period of attending shows, did you keep taking pictures, or was it something that was unique to that moment?

KS: I graduated from Mira Costa in May of 1983 and went to college. I still went to shows during that summer, but starting September of 1983 I was in college and put everything in storage. I began fraternity life. I was drinking heavily and not studying very much. I left the punk rock scene almost entirely until seeing Pennywise in 2011. I put everything away, literally put it in a storage box, for over 30 years.

TS: How did it feel to return to that experience after so long at the Pennywise show?

KS: I felt like a deer in headlights because of the professionals there. I think I missed a lot of shots because of the camera settings. But it was fun. You shoot 1000 pictures on digital to find 10. Back in high school, I took a picture of Keith Morris with a shoe in his mouth at the Goleta Community Center on January 21, 1983. It’s the best picture of Keith Morris ever taken in my very humble opinion. It’s a lifetime money shot. It was fun to go through and find the one photo that stands out. What I’m trying to do now is use technology to make the photos look like they’re on film. Anything that I put on the web or my Instagram is going to be black-and-white. My photos back then were imperfectly perfect. With today’s work, I’m doing it because it’s fun and it’s kind of cool to get back into shooting. But everyone else is doing the same thing and there are people who are a hell of a lot better at it. With the photos from back then, there’s a romance to them. There’s also a scarcity to them. There were not many people who took photos back then.

“Circle Jerks Photo #2” by Kevin Salk (Fathom Gallery)

“Circle Jerks Photo #2” by Kevin Salk (Fathom Gallery)TS: It was this distinct moment that came and went, and you were there to capture it.

KS: It’s overwhelming to be recognized for that. It really freaks me out. But as my daughter said, I’ve been able to find my authentic self. It took a lot of pain and suffering. This has allowed me to go back in time, review that time, pick the parts that are important and delete the parts that aren’t. It’s not just the photos. It’s been a spiritual journey and a life journey. I look in the mirror and I like what I see now. July 22, 2019 changed my life. I was sitting in my office and I got a text from Frank at Fathom Gallery saying, “I saw your work on the internet and I’d like to talk to you.” My reaction was, “What time?” I think I met with him that afternoon or the next day and I signed a contract the day after. I had two photos in a punk rock photography exhibit at Fathom Gallery and everything went hypersonic from there. I was going to have my own photography exhibit right before COVID, my own show in a gallery, to then have my book published. That moment changed everything.

TS: So You’ve been following that path since then?

KS: I’ve been enjoying the path. There’s still a lot of things that are normal. I’m a cyclist, I have daughters, and my girlfriend’s a PhD in Art History. She published a book and she’s working on her next book. I’m in the finance business and I’d rather spend an evening with artists and hear the story of their art than sit and talk to someone who runs a hedge fund. That’s boring.

TS: I share that sentiment.

KS: The art and the people behind it is what’s interesting. It’s been so great to share that with my girlfriend and kids. I have a lot of suits and ties sitting in my closet that I’m probably not going to wear ever again. Part of it’s because of COVID, but also because they don’t represent who I am anymore.

TS: What music are you listening to these days?

KS: In the morning, I listen to classical music. I really like Vivaldi. But my music ranges from Black Flag to Metallica to Pennywise to Slipknot to Gobsmack to Iron Maiden to Circle Jerks to Misfits. I like music that is fast and loud. I love Slipknot. I also love jazz. Classical and jazz calm my soul. I listen to bands now that I didn’t listen to a lot before, like Social Distortion. I’m still evolving.

View more of Kevin Salk’s punk rock photography on his Instagram.