Black Country, New Road. All photos by Taylor Stout.

Look at What We Did Together

Black Country, New Road and Daneshevskaya at Knockdown Center

By TAYLOR STOUT

10.12.23

While waiting outside Knockdown Center on a busy and industrial stretch of Flushing Avenue in Maspeth, Queens, my friend Lily and I noticed two people walking a petite old woman into the venue.

“Look,” said Lily. “Do you think she’s here for Black Country, New Road?”

The woman stood out from the crowd. We had just laughed about how everyone in line for the night’s show looked exactly as we had expected them to. It was mostly twenty-somethings with disheveled hair—somehow in a cool way and not an unsanitary way, or maybe expertly balancing the two—and dark-colored, oversized clothing. Lots of dark eyeliner (I had put more than usual on myself for the occasion; it only felt right). Lots of vintage t-shirts. Lots of denim and leather jackets for one of September’s first crisp days. The autumn equinox was imminent. I could feel the new season closing in.

Lily and I eventually made our way inside and found a space among the packed, buzzing crowd. A few of our friends were somewhere in there. They texted us with vague locations. We shook our heads as we looked at the matching texts on our phones. There was no way we were going to find them.

I took in the space. The stage was in a long room lined with wooden beams supporting a cathedral ceiling. It seemed not quite made for a concert—those beams obstructed the view—but the room was beautiful. The ceiling glowed red, and columns of orange light shone down from it, illuminating eager revelers. A row of windows lined the wall just below the roof. I caught glimpses of the frequently passing planes through them, glowing in the darkened sky.

Soon after, Daneshevskaya began her opening set. At first, singer-songwriter Anna Beckerman was alone on stage, shrouded in dark blue light. She began with a subdued acoustic song. The gentle strength of her pristine voice seemed to hold the room still. When the song ended, her band took the stage behind her.

“Thank you for having me, New York,” she said. “I’m from here.”

Daneshevskaya

It always feels special to be at a hometown show, but especially so for an artist whose work is deeply informed by her family history. Her stage name—which is also her middle name—was passed down to her from her great-grandmother. Her gorgeous, contemplative songs explore how the people who came before us color our lives.

She continued, “My grandma is here,” and looked out into the crowd. Lily and I turned to each other and whispered, “The old lady!!!” Our eyes were wide, our hearts warm. Daneshevskaya continued to list relatives of hers that were in the audience. This gesture turned the audience from a room of strangers to a web of beloved connections. It imbued the songs that followed with the intimacy and depth of personal history. Daneshevskaya and her band dedicated their closing song to a seemingly endless list of people. They kept adding names just as I thought they’d finished, laughing and glancing at each other as if daring themselves to come up with yet another person to honor. While Daneshevskaya is a solo artist, her set was far from individualistic—her music feels like an act of love, something meant to be shared.

After Daneshevskaya left the stage, excitement built in the room as the crowd warped and squeezed close. Her set had held me in a sort of ethereal trance. Now, reality was setting back in: Black Country, New Road would soon take the stage.

BCNR is a band with lore. In early 2022, they posted a statement on social media saying their frontman Isaac Wood was leaving the band to focus on his mental health. Days later, they released the devastating, sprawling album Ants from Up There. Wood’s tortured vocals shine throughout. And we would never hear him sing these songs live—the band had just shifted irrevocably, instantly skyrocketing this music to the territory of myth.

But BCNR made it clear that they planned to continue without Wood. What would they sound like? Would a member replace him as frontman? The answer to these questions came a year later in the form of 2023’s Live at Bush Hall, a live album recorded over three nights in London and consisting of entirely new material from the ensemble. Different members sing different songs, and each one lends a distinct style to the tracks they helm.

Finally, the lights went down. The earnest opening notes of Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’” filled the space from the speakers. In the dark, I could just make out the members of BCNR walking onto the stage and taking their places with their various instruments. They formed a U-shape—piano on the far left, horns on the far right, strings in between, and the drumset farthest back in the middle of the stage. I made my way to the photo pit as the stadium-rock song played. As invigorating electric guitar resounded, I wondered what this distinctly British post-rock band thinks of Americana. You can sort of trace a thread between BCNR and these old hits: while one emanates cutting-edge cool and the other decidedly doesn’t, both are built on vast instrumentation that isn’t afraid to explode into a grand moment of release.

“Don’t Stop Believin’” may seem like a hard act to follow—but not when you open your set with “Up Song,” the opening track of Live at Bush Hall. The first note to ring out was Lewis Evans on the saxophone, and the audience cheered in response. Then, Tyler Hyde sung the opening line, slow and staccato: “Look at what we did together.” As the song went on, its pace picked up and volume rose. The ensemble crashed in.

By the chorus, the song was anthemic. The instruments halted, and the band shouted in unison: “Look at what we did together / BCNR, friends forever.”

May Kershaw (left) and Lewis Evans (right) of Black Country, New Road

May Kershaw (left) and Lewis Evans (right) of Black Country, New RoadMost BCNR songs are not quite as uplifting as “Up Song.” Throughout the set, the band brought an intense technical precision to lyrics about messy feelings like anger, boredom, and unworthiness. Rather than anesthetize the emotions, this style only made them feel more intense, as if they were bursting through some polished veneer.

These songs can sound chaotic—BCNR is a large ensemble with a lot of moving parts—but most of the set was taken from Live at Bush Hall, and not a note sounded out of place from the recorded versions, even the seemingly random ones sprinkled in to create a sense of discord. Seeing the band play live confirmed my assumption: every moment was part of an elaborate construction, landing closer to a classical orchestra than a freewheeling jam session.

I watched the band members communicate with each other through subtle glances and nods. There was no conductor, no clear leader. This precision was an entirely collaborative effort.

Black Country, New Road

In a break between songs, I made my way out of the photo pit and back to Lily in the crowd. When I found her, the stage was still dark and quiet as the band members tuned their instruments. Then we heard the opening note of the one song I’d been most eager to witness live: “Turbines/Pigs,” the nine-minute centerpiece of Live at Bush Hall. It begins with a delicate, twinkling piano from May Kershaw, who is also the song’s lead vocalist. Lily and I grabbed each other’s arms with excitement.

Given that the album version is the first time the audience heard “Turbines/Pigs,” there are no audible voices besides Kershaw’s. The crowd is dead quiet. In time, though, BCNR fans have come to know and treasure this song. The audience at Knockdown Center reverently joined Kershaw for the chorus, singing: “Don’t waste your pearls on me, I’m only a pig.”

It was jarring to hear a room full of strangers sing along—quiet and gentle, loud only as a collective—to these gutting lyrics. What had happened to these people? What had happened to me, that I was here among them, and starting to cry?

All day, I’d been in a stressed daze, and the show hadn’t quite been an antidote to the feeling until this song. As Kershaw sang, “I think I saw some turbines turning beneath me,” I spotted another plane blinking in the sky through the windows. It felt like everyone—the band, the audience, the unknowing strangers on a plane to somewhere far away—was present in that moment together. In a second, the moment passed. Over the next several minutes, the song built and burst and quieted down again. It was dizzying, staggering, sublime.

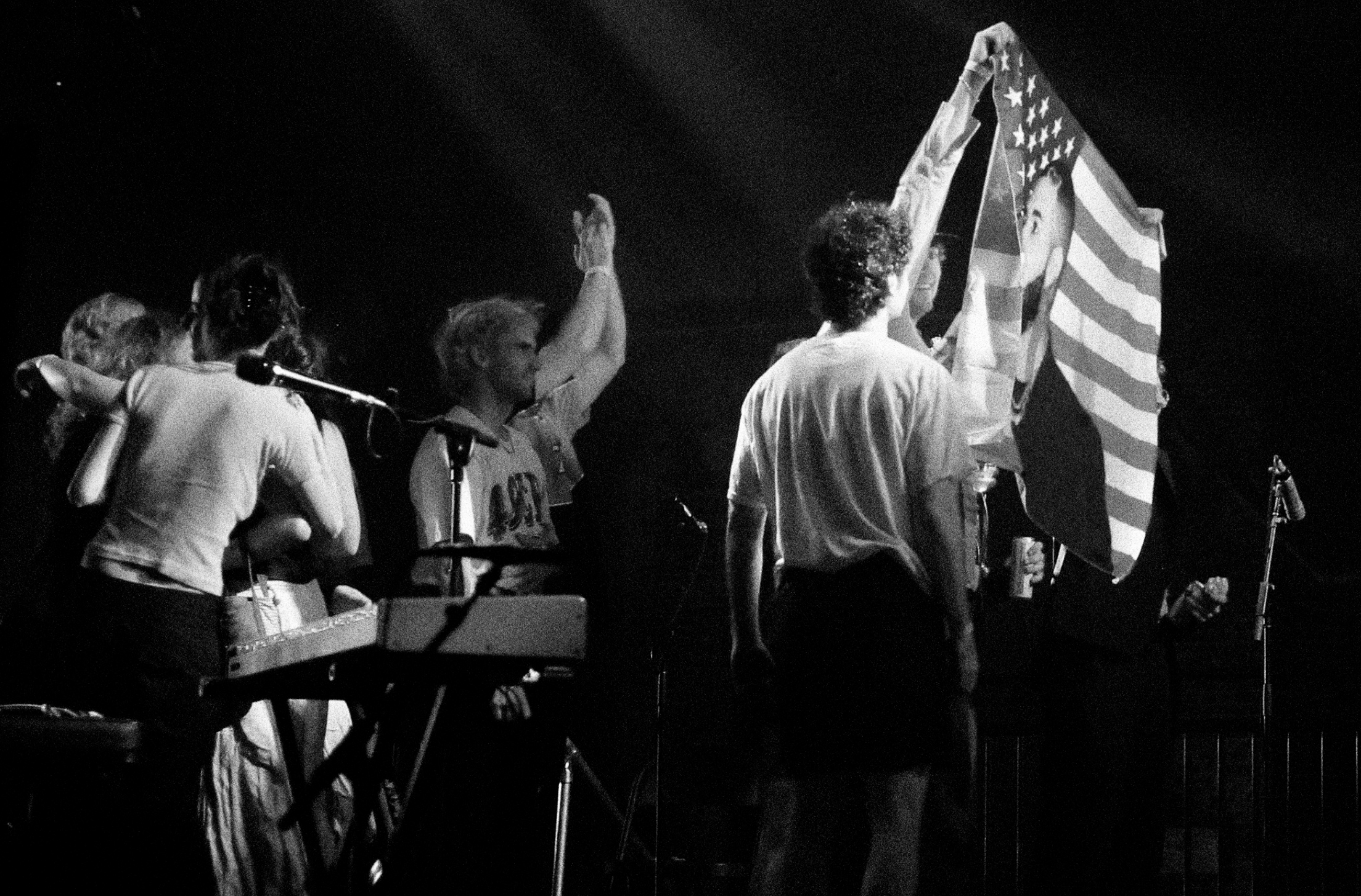

The set ended a couple songs later, and nothing quite touched the presence that “Turbines/Pigs” had put me in. The band didn’t leave the stage immediately after finishing, though. “September” by Earth, Wind & Fire started playing over the speakers. I realized it was in fact the twenty-first night of September. I grinned and laughed—a sharp contrast to what I’d felt a few songs prior. No matter how bleak their music gets, BCNR brings with them a sense of humor and a genuine appreciation for sound with big feeling. Crew members ran on stage from the wings. They poured a champagne toast. Daneshevskaya and her band came out, and everybody was hugging and congratulating each other. From the crowd, Lewis Evans grabbed a big American flag stamped with Drake’s profile. With the help of some others on stage, he held it up valiantly and the audience cheered. The exuberant disco song blasted.

Black Country, New Road and friends

Black Country, New Road and friendsThe ensemble lined up, put their arms around each other, and took a bow. It resembled the ending of a Broadway show or Carnegie Hall performance more than your standard rock gig in Queens. But it was a perfect send-off for this odd, orchestral band.

After the band left the stage, the audience dispersed only slightly. Hangers-on waited desperately for an encore that didn’t come. Lily and I moved to the side of the room where the crowd was thinner and searched in vain for our friends’ familiar faces.

After a minute or two of this, I sighed and went, “Where are the guys?”

Lily joked, “Yeah, there’s not enough men in this room.”

I looked around. There was in fact an abundance of men. At that moment, I leaned in and said, “Don’t look, but my friend’s ex-boyfriend is right behind you.”

She said, “No, YOU don’t look, the bartender that [redacted] was into is right behind YOU.”

We laughed and went outside before we accidentally locked eyes with someone more consequential.

We eventually caught up with some friends outside the venue and parted ways with them on Flushing Avenue. Lily and I headed off into the quiet streets. We chattered and gossiped in the dark. “Up Song” echoed in my head. We sang a line from it back and forth, over and over, as we made our way back home: “Look at what we did together / BCNR, friends forever.” Only amid darkness—on a gutting album, on a desolate city street—does that childlike sweetness feel so right.

Black Country, New Road