WHO’S THE BOY YOU LIKE THE MOST #1, Eden Chinn and Milo Hume, 2024

Reminders of Existence

A show at All Street Gallery asks: What do you do to remind yourself that you exist?

By Naava Guaraca

09.10.2024

Something about New York City post-2020 feels different than I remember. I grew up in Manhattan but now live in Queens, and whenever I trek back to my old borough, I find myself asking: Were there always this many people here? Maybe I was blindsided by the self-absorption of childhood, unable to really take in the world around me. But I’ve always been the kind of girl who spends a lot of time walking the streets alone. I swear something is different.

When I enter All Street Gallery on East Third Street between First and Second Avenues, I’m excited to be visiting a community-based gallery operating within the same streets as the fabled downtown art scene of the 1960s and 70s. In Hold On to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973-1992, author Tim Lawrence describes Allen Ginsberg’s old apartment on nearby Tenth Street and Avenue C as a “dystopian wasteland.” From these sites of decrepitude came a generation of true avant-garde art makers. To quote Marvin J. Taylor’s The Downtown Book, which Lawrence also references: “The value of Downtown works emanated from the symbolic capital Downtown artists received from their peers. Artists worked in multiple media, and collaborated, criticized, supported, and valued each other’s works in a way that was unprecedented.”

While the East Village now feels far from the “dystopian wasteland” that Lawrence describes, All Street’s Reminders of Existence is a show that celebrates a similar ethos of collaboration, support, and multimedia conversation. Curated by Aleksandra Dougal, Maya Rajan, and Cora Hume-Fagin, the show features works by four artists responding to the question: What do you do to remind yourself that you exist? The space is small and intimate, and the pieces hang on the walls in typical gallery fashion. When I see the show at four o’clock on a Sunday, beautiful mid-afternoon light streams in through the street-level, floor-to-ceiling windows.

Shradha Kochhar’s The Chair hangs on the wall adjacent to the entryway and looks like two bodies intertwined. There’s a tension within the contrasting styles of knitwork—some parts are intricate and fine, while others are made with a heavier yarn. As Dougal says about the content of the show: “Sometimes the reminders [of existence] are super mundane, sometimes they're rituals, sometimes they’re conversation.” It feels intentional that this piece is the first one I encounter upon entering. In a world pillaged with violence, the tenderness of The Chair reminds me that dedication to one’s craft can serve as a method of endurance through the world’s harsh reality. I imagine Kochhar returning to her piece at the end of a long day, stitching her way through the intensity of life in New York.

The Chair, Shradha Kochhar, 2021

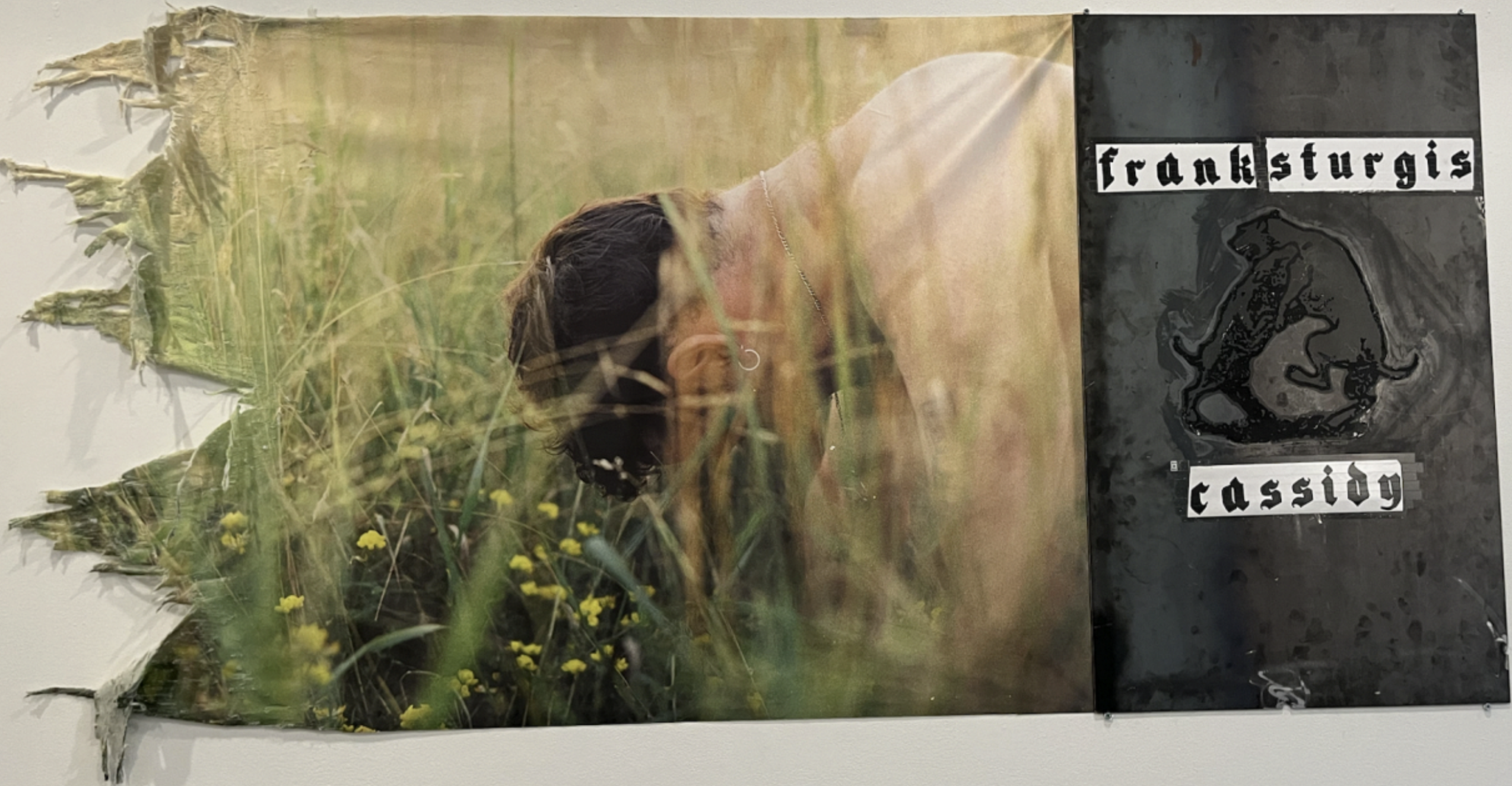

All Street co-founders Eden Chinn and Milo Hume have been friends for a while and, prior to this show, had been discussing the possibility of collaboration. The two pieces they’ve made together, WHO’S THE BOY YOU LIKE THE MOST #1 and WHO’S THE BOY YOU LIKE THE MOST #2, sit opposite one another and are each composed of engraved iron plates placed atop pieces of delicate fabric. Hume is the subject of both pieces, photographed facing the camera dead-on in #2 and bent over toward the earth in #1. Exploring ideas of masculinity, WHO’S THE BOY YOU LIKE THE MOST #1 is the largest physical piece in the show. It’s also the most captivating.

WHO’S THE BOY YOU LIKE THE MOST #1, Eden Chinn and Milo Hume, 2024

I’m reminded of the late Pope.L’s larger-than-life Trinket, created in 2008; that flag stood next to four large fans that perpetually propelled its fabric to wave in the wind, eventually causing it to tear at the seams. Unlike that flag, which wasted away on its own, WHO’S THE BOY YOU LIKE THE MOST #1 has been altered at the hands of Hume and Chinn, cut up haphazardly without clear direction. This inflection of violence in response to a soft, intimate image lends to the dichotomy of masculine/feminine that Chinn and Hume investigate. Situated atop the right half of the piece is a sheet of iron that reads “frank sturgis cassidy”—Chinn says that Hume “made a list of the most masculine sounding names he could possibly think of,” and then started thinking about traditional symbols of masculinity, where he came across the image of two dogs fighting.

Opposite this flag sit two pieces of canvas side-by-side with another image of Hume printed on them. In the photo, Hume stands looking at the camera with his hand partially covering his mouth. These two pieces function as large sketchbook pages—while they aren’t as technically strong, I admire the tenacity of the curators to display a prototype next to the “successful one.” As Marina Abramovic says in her memoir, “The process is more important than the result.” Lots of small DIY exhibitions these days are allowing artists to put their sketchbooks on display, an act that deviates from typical curatorial practices—rather than only seeing selected final products, we’re allowed insight into the process and time it often takes to create art.

Interspersed between pieces by Hume, Chinn, and Kochhar are drawings and paintings by Abby Wang. These two-dimensional works lack a certain intensity that the other pieces in the show possess. Rather than the thought-provoking confrontation I feel while examining The Chair, Wang’s works function as reminders of tenderness as a subset of existence. On the back wall of the gallery is a small screen that resembles the moving-picture frames my parents had in the early aughts. On this screen, Hume’s Passing Time runs for just over four minutes and depicts Hume and a friend wrestling atop a bed, set to an audio track of younger boys wrestling. The film is tender and childlike, reminding me of the characters I’ve come into contact with thus far—Wang’s depictions of herself and a friend, Hume in various poses—and leading me to imagine them as a group of friends hanging out.

Passing Time, Milo Hume, 2024

After watching the two boys in Passing Time, I think back to these other characters—the figures, the fabrics, the marks made. They’re talismans of life as a young, postgrad artist wading through the murky territory of making art in New York. It’s a battle I’m familiar with: every day, I’m relearning how to slow down, pay attention to the details of life around me, and engage with it in a way that feels thoughtful and healthily critical. In the nooks and crannies of tenderness, shame, anger, and joy, I find reminders of existence; I find them in making art, too. A group show like this one feels like time spent reveling in the no-strings-attached aspect of artmaking. Sometimes it’s enough to just ask a question and endlessly search for the answer.

Reminders of Existence is on view at All Street Gallery, 77 East Third Street, New York, NY 10003, through September 13, 2024.