PREMIERING ON COPY:

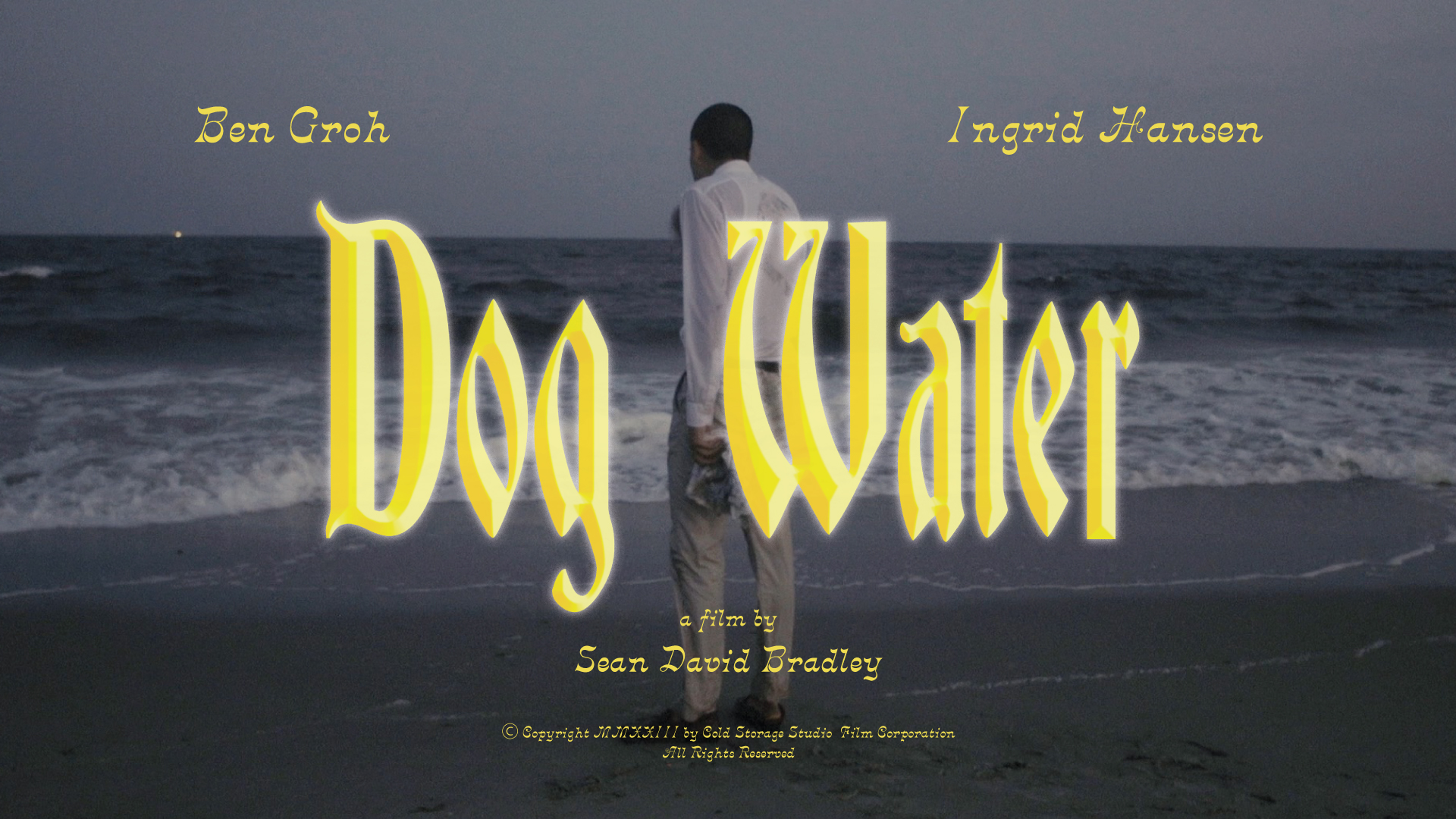

The Cult Member from the Ocean and the Clown on the Beach: Sean David Bradley’s “Dog Water”

“Dog Water” captures the sense that we’re all prone to the same very human tendency toward absolute faith.

By lizzie racklin

07.19.2023

Filmmaker Sean David Bradley used to be friends with a member of the Church of Scientology. The guy was chill about it; Sean didn’t even know at first. They worked together on a few films, and Scientology came up rarely, if at all. But after their second film together, his friend sold his car, erased his email and phone numbers, and retired from the arts. Now a full-blown missionary, he would call up old friends and encourage them to buy Scientology literature. The last time they talked, he’d say, they seemed pretty unhappy, and Scientology might help.

Sean not only had to mourn his friendship with this person, but also had to process this use of their friendship as a book-selling tactic. It was a complete personality shift, one that felt jarring and manipulative, but his friend saw this new life as purely altruistic.

This experience is what led to Sean’s new short film “Dog Water,” in which a cult member (Ben Groh) crawls out of the ocean and tries to sell a woman (Ingrid Hansen) a Bible. The short is an anxious conversation between two strangers, one of whom—Ronald, the cult member—knows a lot about the other—Emily, a painter who is just trying to read on the beach. He uses her family history, her past relationships, and her struggling artistic career to convince her that the soaking wet book in his hand, the primary literature for his religion “Humble Divine,” could turn her life around.

Ben plays Ronald with a white-knuckle grip. He’s on such high alert that you might think he’s prey, but he’s so calculating and determined that you come to see that he’s really the predator. As in his performance in last year’s God’s Time (dir. Daniel Antebi), he lends his character an intense but somehow sympathetic desperation to convince everyone that he’s right. He has a deft, non-stop ability to jump between voices, moods, and postures. It keeps you on your toes and forces Emily to start packing up her things.

As Ronald tries to appeal to Emily’s vulnerabilities, she gets angry, which makes Ronald angry, which makes Emily even angrier. Ingrid and Ben bounce off each other, improvising within the beats that Sean outlined for the story. As the four of us talked about the film, Sean told me that in between the three takes they shot, he told Ben and Ingrid to keep ramping it up. The last take, where it started to feel really unhinged, is the one they used.

Watching the short, the characters’ interaction is so engrossing that you almost forget that Ronald emerged from the ocean. When he returns in the end, there’s a sense of peace—this high-octane argument came and went and now the beach is empty again. Sean wanted Ronald’s connection to the water to give the audience a sense of universality. We all come from the same place, and, in the end, we can’t say that our reality is more objective than anyone else’s.

Our instinct might be to discredit Ronald, but, as captured in the final shot of the film, Emily also leaves their conversation feeling like (and suddenly dressed as) a clown. Ingrid sees this last image as a signifier that Ronald and Emily are no different from each other. She asked, “What is life? What is real? I’m thinking my life is real, reading this book on the beach, but what am I doing? At the end of the day, [Ronald’s] no more wrong or right than me.”

When someone believes in something that you don’t—a god, a myth, a version of the truth—it’s hard not to think that they’re consciously lying to themselves. It’s strange that they could have wholehearted belief in something that you see as fiction, but “Dog Water” captures the sense that we’re all prone to the same very human tendency toward absolute faith. It’s also very human to get offended when someone doesn’t believe you, even if you know that you’re lying. Ronald might believe everything he’s trying to sell Emily, or he might just be irritated that she’s not convinced by his pitch.

I asked Sean, Ben, and Ingrid if they think anyone could be convinced to join a cult, and the consensus seemed to be that, if the right person comes to you at the right time, yes, anyone might be susceptible. Everyone likes to think that they would never be convinced by the preacher on the corner, or the snake oil salesman, or the flat-tummy tea evangelist, but as Ben pointed out, “We live in a pretty cynical world. And something that can tap into something more significant and sincere is a huge draw for a lot of people.”

Sean didn’t make “Dog Water” to undermine his friend’s faith in Scientology, but to understand the mechanics of belief and capture the dissonance between two people who see the world very differently. It’s easy to paint someone else as a fool, but maybe being so certain that you’re the one in the right is actually what makes you the clown.

Poster by Luca Schenardi

Note: this interview was conducted before SAG-AFTRA declared their strike.

--

Watch “Dog Water” on Vimeo here.

Ben Groh: https://www.instagram.com/grohb12/

Ingrid Hansen: https://www.instagram.com/inn_u_endo/

Post-Production by Peter Buckingham: https://www.instagram.com/peterbuckingham/

Music by Grey Keith: https://www.instagram.com/what_a_chill_dude/

Cinematography by Alejandro Benito: https://www.instagram.com/alejandrobenito/

Written and Directed by Sean David Bradley: https://www.instagram.com/cornholiwoah/

Sound Recordist: Eunice Chung

Associate Producer: Cassie Hoeprich