Smithereens:

The Anti-Romantic Comedy

Like many before her and plenty after her, Wren is on a mission to find her own rom-com ending and will do whatever it takes to get there.

By BROOKE METAYER

3.23.2022

It’s a Tuesday night around 8 pm and I slouch into the indented corner of my green suede couch, mentally and physically preparing for a movie night. My roommate sits across the couch with her legs propped up on the coffee table. Without looking up from her phone screen that glows with hundreds of little rectangular movie posters, she asks, “What’s the vibe tonight?”

“Something predictable,” I say. “Like a rom-com.”

After a long day of existing inside my own head, reflecting on the choices I make, how I am perceived, and my place in society, I don’t want to think about the confines of reality. I want to be liberated from my daily concerns and dumped straight into a beautiful fantasy where there is no real responsibility or risk. I know a romantic comedy will deliver at least 90 minutes of just that. This genre of charming, idealistic movies practically guarantees happy endings.

Though rom-coms are often criticized for their formulaic tendencies, this predictability is a huge part of their appeal. A genre built so heavily on tropes makes us feel at ease. When so much media seems to be interested in the worst sides of the human experience, engaging with media that isn’t trying to teach you anything is refreshing.

That Tuesday night, after browsing every corner of the streaming platform universe, we eventually decided on the 1982 film Smithereens, and I haven’t been able to get it out of my head since. If romantic comedy is the comfort food of cinema, then Smithereens is the sugar-free raisin bran muffin you mistook for chocolate chip.

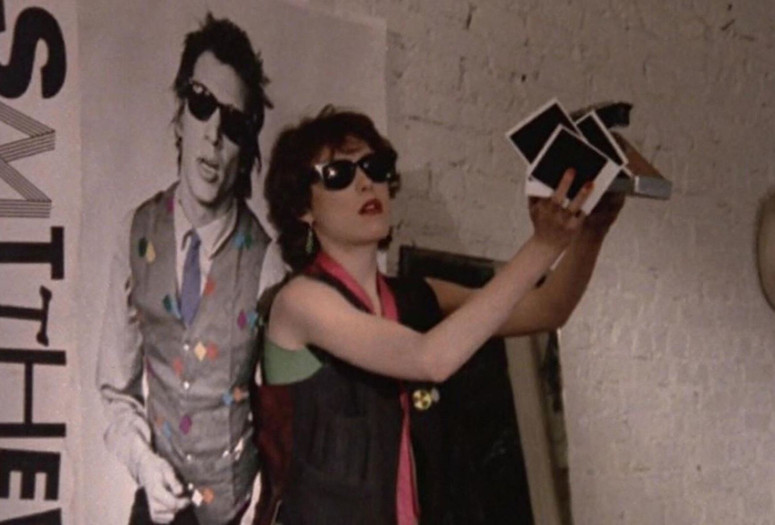

Smith, directed by Susan Seidelman, follows untalented Jersey girl Wren (Susan Berman) as she roughs it in New York City. She sneaks into nightclubs, smokes cigarettes with rock stars in messy Manhattan lofts, and navigates complicated relationships with other young transplants as she runs down the city streets towards dreams of stardom.

Based on this “SparkNotes version” plot description, you might throw the film into the pile of idealistic coming-of-age stories about lost souls finding their way in the city. In these stories, New York City is a place of endless possibility where your wildest dreams come true and you find your soulmate in the process. But when watching the film, you realize that Seidelman is actually subverting every one of those cliches. There is no makeover montage, no friends fighting just to have a tearful reconciliation a few scenes later, no friends-to-lovers arc. No happy ending. Even the usual autumn leaf-littered sidewalks and chilly walks through Central Park are replaced with trash-piled parking lots, vandalized stairwells, and peeling paint on bedroom walls.

Despite how unappealing this may seem, Smithereens is an influential and entertaining piece of media—just for different reasons than one may initially think. I recently found myself trying to convince another friend to watch the film so we could compare and contrast our thoughts on it (as friends do), but I kept stumbling over my words and backtracking my vague plot descriptions. I was trying to communicate why this random indie film made nearly 40 years ago was so refreshing to me. It came down to this: Smithereens is the antithesis of the modern rom-com.

The opening sequence feels familiar: we watch a girl in a mini skirt steal a pair of checkered sunglasses without fear of consequence. We hear the guitars in The Feelies’s “The Boy With The Perpetual Nervousness” speed up, taking our adrenaline levels with them as our protagonist runs down the subway stairs in her fishnets and glittery shoes with clashing striped socks and jumps into a graffitied car. Chewing her gum, she begins pasting flyers over maps as the cute guy sitting across the way steals flirty glances. Seems like you’re in for a quirky story about a rebellious, witty girl who can’t be tied down but meets her perfect match when she was least expecting it, right? But don’t get too comfortable, because instead of celebrating the characters you are meant to identify with, Seidelman takes your attention and uses it as a chance to critique them.

In 1982, when the film was released, New York City was seen as a refuge for artists, punks, and weirdos escaping their small towns—dangerous but liberating. Former Sonic Youth bassist Kim Gordon describes the excitement of driving into the city for the first time in her memoir Girl in a Band, saying it was “as if your car were being shot from a pinball machine, down a slope into some rough forest. It was all unknown and possibility.”

Wren longs for this. To be a scenester. One with the punk rockers. But she lacks the ability to create anything of value apart from her own image. Through Wren, the viewer explores a lifestyle they once longed for too, but come to realize it’s really just a lot of pain, lying and manipulation by a bunch of attractive people with toxically vetted idiosyncrasies.

Smithereens’s contrarian flare doesn’t stop there as it proceeds to dismantle the sacred and time-honored friends-to-lovers trope.

Rob Reiner and Nora Ephron’s 1989 film When Harry Met Sally created the blueprint for the modern rom-com (don’t even try to fight me on this). From the snappy back and forth dialogue to the feisty lead woman, the film undoubtedly defined the genre—and the whole gimmick of the film was watching an unlikely pair realize that they should be together.

Smithereens says “fuck that” and does the complete opposite to a nearly comedic degree. The well-meaning boy who sees something in her when no one else does is present, but his endless pursuit is not rewarded. Paul (Brad Rijn) is a nice guy from Montana living in his multicolored van as he roadtrips to New Hampshire with the money he has saved up. He is captivated by Wren and shows clear interest in her as he runs after her out of the subway and proceeds to follow her around town like a well-trained puppy. Despite his striking jawline, financial stability, and gentle demeanor, he cannot offer her what she really wants: social status. Wren keeps him around but repeatedly ditches him to vie for a morsel of attention from scummy one-hit wonder musician, Eric (Richard Hell). This is what we in the industry call “clout-chasing.”

In When Harry Met Sally, Harry gives a passionate monologue describing everything he loves about Sally, saying, “I love that you get cold when it's 71 degrees out,” and, “I love that you are the last person I want to talk to before I go to sleep at night.” (Thanks, Norah, now I’m crying.) But Siedelman opts for a much colder resolution as Paul, finally fed up with Wren's abuse, sells the van and quietly continues on his own journey, leaving Wren with nothing but an empty parking lot.

Becky in Confessions of a Shopaholic, Molly in Uptown Girls, and Jules in My Best Friend’s Wedding represent a certain brand of rom-com protagonist that comes off as messy, shallow, and self-involved, but we love them despite their flaws. These charming lead women make mistakes and hurt people close to them, but only at the expense of a major life lesson.

Wren, however, never learns from her mistakes and no one sweeps her off her feet to take her on some metaphoric adventure to change her fate. The love interest who actually does try to help her gain some perspective is rejected. In a final plea to evoke some humanity from Wren, Paul tells her, “Other people have feelings too.” To which she responds, “New Hampshire? I don’t even like trees.”

Throughout the film, Wren proves herself to be an extremely unlikeable and irredeemable person. We watch her attempt to join the dying punk subculture, engage in a number of parasitic relationships, and constantly shift her allegiances to new "friends" in her effort to attach herself to someone who will support her desired lifestyle and validate her delusions. She never shows signs of even wanting to change, apart from asking Paul one night:

“Tell me the truth, am I like really awful or something?”

Siedelman’s New York City is laid out like a battleground. Using 16mm film that captures the grit of Downtown in the ‘80s, the camera follows Wren as she weaves through discarded cardboard boxes, three-foot-tall piles of trash, and unsupervised children jumping on abandoned cars. Graffitied brick walls stacked around her stretch into space, locking her into this post-apocalyptic wasteland. Wren tells Paul she had a dream where the world had been “blown to smithereens” and people were still living in the debris, not realizing what had happened yet.

While Siedelman does opt for a more cynical tone in her story about being poor, artistic, and aimless in the city, she avoids creating something so grim that it is unwatchable by incorporating more playful elements throughout. The use of bold colors and witty, deadpan dialogue (such as: “You know everything, don’t you?” “No. Just everything important.”) do not go unnoticed. There is a time and a place for a true, blistering critique on the misplaced glorification of New York City, but Smithereens doesn’t want to take itself that seriously. In a 2016 interview with Vogue, Siedelman explains how she found this balance:

“In studio movies, it tends to be very black and white: I was thinking about Pretty Woman recently, and how different the original script is from the movie. Studio movies had to clean up their leading ladies—if she’s a prostitute, she’s a Julia Roberts type, a nice-girl prostitute. But I wanted to keep Wren gritty. So she makes mistakes and she doesn’t have the best judgment at times, but when she gets knocked down she picks herself back up. It was that resilient quality that I admired.”

Through a brilliant, biting script, unexpectedly whimsical design, and intimate cinema, Smithereens tells a cautionary tale, but also one of resilience. Like so many before her and plenty after her, Wren is on a mission to find her own rom-com ending and will do whatever it takes to get there, even if it means contributing to the ever-growing pile of carnage that is New York City.