![]()

The Hour of the Star and Self Deprecation

A REVIEW OF CLARICE LISPECTOR’S NOVEL RIPE WITH EVERYTHING BAGELS AND MUSINGS ON CRITICISM OF THE SELF.

By PHILIP KENNER

7.14.2021

I had 5 hours to burn in Manhattan. My

older sister, a true mensch, picked me up

from the airport with an Everything Bagel in

tow. “What do you want to do before

dinner?” My gut response, worthy of a

thousand eye rolls, was, “I want to go to

McNally Jackson.” She kindly schlepped me

from LGA to SoHo.

My friend and fellow readcopy.co literature team member, Jack Petersen, was working at McNally that day. We gave emphatic hellos and air hugs from behind our facemasks.

As though I were at a diner, laminated menu in hand, I asked, “So what’s good?”

My friend and fellow readcopy.co literature team member, Jack Petersen, was working at McNally that day. We gave emphatic hellos and air hugs from behind our facemasks.

As though I were at a diner, laminated menu in hand, I asked, “So what’s good?”

The Everything Bagel.

My secret shame combusted in my gut – I had never read Clarice Lispector, despite pretending to at parties. I owned a different Lispector novel - Near to the Wild Heart - for three years and never made it past the first page. What a bullshit fraud I was. How dare I waltz into this bookstore, look at my cool friend, and pretend to be well-read.

The truth slimed out of me like a baby horse from its mother. “I’ve actually never read Lispector.” Jack reassured me that The Hour of the Star was a great place to start. Then they went back to their job that I was no doubt interrupting with my silly, convoluted guilt.

Over the next two weeks, I nibbled my way through The Hour of the Star, the last novel Lispector wrote before her death in 1977, humbled at how many times I had to go back

and reread paragraphs. The fuck is this narrator talking about? Why does he keep repeating himself?

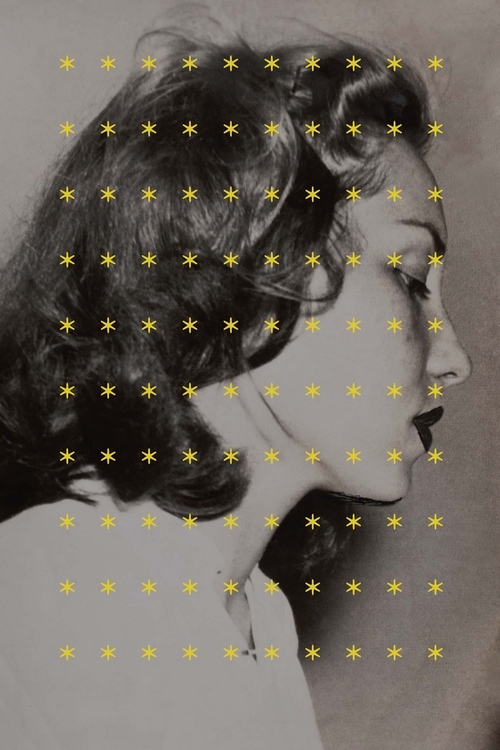

The Hour of the Star, 2011. New

Directions Publishing. Cover design by

Rodrigo Corral.

(You know what didn’t help my reading? Strep throat. I got strep throat! Strep G, specifically. I tried to read this novel in an Urgent Care while the waiting room TV blasted The Kelly Clarkson Show at a volume meant to torture war criminals.)

Rodrigo, a metropolitan sad sack with a penchant for self-pity, narrates the story. He is obsessed with Macabéa, a typist from Rio, and he struggles to tell a story about her misfortune. His visions of her life torture him. He wrestles with different storytelling techniques. Macabéa’s journey, even when he finally gets to it, never takes center stage for longer than a few pages. Our narrator continuously butts in with biting, self-critical uncertainty about his own ability to tell the story. Bad things befall Macabéa relentlessly. She is almost cartoonish in her destitution. Eventually, the narrator decides he’s done writing this sad, unbearable story, and the book ends. Seventy-seven pages, and it’s over. A small book, but not a quick read.

In his introduction to the 2011 translation, Colm Tóibín writes of the narrator: “...he is also alert to the writing of fiction itself as an activity which demands tricks that he, the poor narrator, simply does not possess, or does not find useful... It is hard to decide who to feel more sorry for, Macabéa or the narrator, the innocent victim, or the highly self-conscious victim of his own failure.”

I’m combing through my annotations of the book, desperately trying to find a passage that will encapsulate this narrator’s agony. It would be helpful if I didn’t underline 90% of the sentences in every book like a serial killer. I had the same issue when I was in elementary school; I would highlight with an indulgence that bordered on delinquency. Every textbook page would be a moist, neon blue by the time I was through.

Our narrator writes, “I’ll try contrary to my normal habits to write a story with a beginning, middle, and ‘grand finale’ followed by silence and falling rain.” This on page 5. He’s already making fun of himself.

After admitting that no reader will truly care about Macabéa, he continues, “Moreover – I realize now – nobody would miss me either. And even what I’m writing somebody else would write. A male writer, that is, because a woman would make it all weepy and maudlin.” There’s a fun, ironic nod to Lispector herself, the real narrator behind the curtain. Rodrigo reveals his own backstage to be a panoply of self-made torture devices, the writer’s residency from Hell.

This book is like two simultaneous puppet shows, one of them tragic, the other sardonic. Here’s this narrator, beating himself up all the way until the last page, trotting out Macabea’s maudlin mythology, one that he has invented for his own misery. Behind him is perhaps an arguably crueler entity: Clarice Lispector, representing self-deprecation and doubt with unflinching hilarity.

What are the benefits of self- depreciation? Is there something deeper inside self-pity, a lesson to learn? Does it change if the speaker is fictional? Is self- deprecation like the stink spirit in Miyazaki’s Spirited Away: a force of good, suffocating in a putrid slosh of shit?

“Stop feeling sorry for yourself!” I’m tempted to scream at Lispector’s narrator, as though he were a friend sulking after a bad hookup.

The Stink Spirit in Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away (2001). Image from http://www.sinema.com

I tell my students that they are not allowed to apologize before presenting any work. You may not qualify, dampen, or preface your writing in class.

In the classroom, I discourage the many forms self-deprecation can take. There’s the evergreen, “This isn’t my best.” There’s also the classic, “I wrote this super late last night.” Or, even better/worse, the self-aware version: “I know we’re not supposed to qualify our work before presenting, but...”

I understand the impulse to place oneself in the damp cellar of criticism before someone else gets to it first. I’ve definitely had a thought like: “They’re going to think it’s bad. I need them to know that I also think it’s bad so they don’t think that I think it’s good because I don’t want them to think I’m cocky when really I know I’m a little poopy diaper baby who shouldn’t be trusted to write a fucking grocery list, let alone a piece of fiction.” Lispector’s narrator lives in that wavelength, and it’s spectacular to watch. I never settled into Macabea’s story. How could I, when the narrator was second guessing himself at every turn? Even still, I loved the book.

Isn’t self-pity supposed to frustrate me? I try to train this impulse out of my students, collaborators, and myself, and yet when Lispector builds The Hour of the Star on a foundation of self-deprecation, I’m mesmerized.

When I try to imitate this self-deprecation, as I have tried to do at moments in this very essay, I feel gross, like I’m performing a strip tease while covered in Caesar dressing. Hannah Gadsby puts it best in her 2017 special, Nanette:

"I have built a career out of self-deprecating humor and I don’t want to do that anymore. Do you understand what self-deprecation means when it come from somebody who already exists in the margins? It’s not humility, it's humiliation."

Whenever I give voice to the thought that I’m a sack of hot, juicy garbage, I see all my Jewish ancestors on a boat, sailing across the Atlantic, clinging to tiny leather suitcases and wrapping their heads in beige scarves. They stare daggers at me, tell me to shut the fuck up in Yiddish, and then start coughing, probably because they have Jewish-boat-flu. (I’m not a doctor.)

Why bother insulting yourself? For whose benefit do you make yourself miniscule? There have been times, whether during sex or collaboration or receiving mentorship, that I have tried to make myself as tiny as possible. Have you ever tried to be so accommodating that you practically vanish, the borders of your body and desire obscured entirely by your own fear? Why do we do that? Intimacy is best when it's reciprocal, so why do we think our lovers and confidants will have more fun if we become miniature, like a slutty Stuart Little?

Does the same give-and-take relationship exist in literature between a narrator and their audience? Why undermine our own authority before we start? The audience wants us to tell them a story, after all. If they didn’t want to hear what we had to say, they probably wouldn’t have bought the book.

Self-deprecation has a circular logic. If we don’t devalue our work before somebody else does, we live in fear the world might find out we’re phonies. However, if we choose to apologize for creating, we usually end up feeling shittier than when we started, making its repetition all the more tempting. Is our only other option to perform confidence?

The Hour of the Star asks its readers to trudge through the mud, to bear witness to a narrator trapped in his own seesaw between “I’m a genius” and “I’m the worst writer who has ever lived.” Lispector locates us inside of this neurosis, slapping our hands to the sticky cave walls and blowing out our torch.

Is the takeaway, then, that self-deprecation can be a generative step in a writer’s process? No, that can’t be it. Maybe it’s something closer to an omen. Here, Lispector begs, look at what happens to a narrative suffocated by pity and doubt. Watch the storyteller writhe in shame.

Rio exists only to torture Macabéa, to erode her free spirit. In tandem, our narrator withers in the wind. As he describes Macabéa slipping into nothingness, his ability to keep telling the story follows suit. His art is so attached to his sense of self that his failure to tell the story becomes a failure to exist. Lispector warns us that our art, whether narrative or otherwise, is a much weaker life raft than we’d hope. By the time we demand that art carry our heavy sense-of-self, once we decide it’s either “make good art” or “be a bad person,” we’re doomed to drown. Our lungs aren’t meant to take on water like that.

The Hour of the Star is a book full of sharp but self-aware teeth, begging to be brushed. After my sister picks me up and I eat that bagel, I check my mouth in the visor mirror.

There are poppyseeds stuck everywhere. I wish I brought floss. I look ridiculous.