The Wizard of Oz (1939)

What Kind of Witch Am I?

Wicked, Weapons, and the Malleus Maleficarum

By Abby Brooke

2.12.2026

In The Wizard of Oz (1939), after Dorothy accidentally house-murders the Wicked Witch of the East, Glinda the Good inquires: “What kind of witch are you? A good witch, or a bad witch?” Dorothy looks scandalized. “Who me? I’m not a witch at all.”

Loser. When I was a little girl, all I wanted was to be a witch.

I attempted to cast spells on my bedroom floor, using Christmas candles I stole from the wooden cupboard downstairs and twigs I gathered from the yard. My image of a witch was not wart-spotted or ugly. It was a clever young woman growing into her powers. Her magical abilities were sometimes misunderstood or unwieldy, perhaps even slightly dangerous when untrained, but always ultimately an expression of her own true spirit. As a tail-end millennial, I grew up on a steady cultural diet of witch-as-empowerment symbol. It was the era of good-hearted know-it-all Hermione Granger, Buffy’s nerd-turned-Hot-Lesbian Willow, and Halloweentown’s apple-cheeked Marnie. Every Thursday night, my family all sat together to watch Sabrina the Teenage Witch as she juggled math class and spells gone wrong to a laugh track prompted by zippy one-liners from her sassy black boycat, Salem.

These witches came in many varieties, but I identified with all of them. I was meant to. They were academically inclined everygirls who were going through the same trials and tribulations of adolescence that I was. They just happened to be able to levitate objects or shoot lightning out of their fingers.

The one thing they were not was scary. I remember scoffing at my mother when she told me about how terrified she was of the Wicked Witch of the West as a child, how frightening she found her iconic cackle, her dog-centric threats. Tween-me was confused. You think the Wicked Witch of the West is scary? You mean my close personal friend, Elphaba Thropp?

I cannot overstate the cultural impact of Wicked, the ultimate witch-apologist text, on theater kids like myself. Elphaba is yet another bright, bookish young woman, misunderstood for the “weird quirk” of her green skin and magical abilities, who masters her powers in order to unmask the true villains: bigotry, propaganda, and men in show business. The stage musical premiered on Broadway in 2003, when I was nine years old, and has been running on a loop in the back of my brain ever since. On my deathbed, I will still be able to sing every word of “Defying Gravity.”

In 2024, the long-awaited film adaptation of Wicked defied the gravity of a lethargic theatrical market to the tune of $750 million worldwide, plus ten Oscar noms, including Best Picture. The second installment–Wicked: For Good–has already surpassed the first in terms of opening-weekend box office cha-ching, though the critical response has been mixed. It would appear that the protagonist witch of my youth is still flying high in mainstream mythology.

Wicked: For Good (2025)

Wicked: For Good (2025)And yet. Another kind of witch has crawled out of the deep, dark woods of our cultural consciousness and onto our film screens. Old and haggard, hideous and stooped, wizened and feral, her power is not her own–it is not the result of long study, communion with nature, or genetic gift. It is on loan from the darkness, from Satan himself. She is the witch of early modern Christian imagination, an unholy seed planted as far back as the witch hunts of 14th-century Europe. She is not a perky young woman, juggling boyfriends and math class and spells gone wrong. No, she has other priorities: primarily, child abuse. Most notably, she has emerged in a surprising arena: the “elevated horror” film of the 2010s and 2020s.

______

Zach Cregger’s Weapons (2025) centers on an everytown in America, conjuring what feels like a particularly American nightmare: an entire class of third graders, save for one, vanish overnight. Caught on nest-cams and security feeds, the children exit their homes at exactly 2:17 AM, sprinting Naruto-style into the darkness like homing pigeons towards an unknown destination. Their teacher, Justine (Julia Garner), becomes the prime suspect for the bereft parents, particularly MAGA-coded Archer (Josh Brolin), who goes so far as to paint a blood-red brand—“WITCH”—across her sedan. What seems like a clear indictment of a “witch hunt” turns out to be something much less subtle: the filmmaker telling us, in bright red letters, what we have to fear.

The film is a Roshomon, inhabiting six perspectives, doubling back on itself to partially retell the previous story beats through the eyes of a different character: schoolteacher Justine, angry father Archer, troubled cop Paul (Alden Ehrenreich in a fantastic mustache), gentle school principal Marcus (Benedict Wong), addict James (Austin Abrams), and finally, in its most shocking chapter, lone surviving third-grader Alex (Cary Christopher). It is in this final chapter that the truth of where the children have gone and why is finally revealed, and the real witch finally looks us in the eye.

Though the villain is teased through dream sequences, the camera doesn’t show her in full until we enter the perspective of Marcus Miller, the well-meaning school principal. He has requested a meeting with the adult responsible for Alex, the lone remaining third grader. At first, Alex’s Aunt Gladys is simply hilarious. She floats into our frame through the foggy pane of a window, just a bobbing red wig wending towards the entryway to the principal’s office. When she finally rounds the doorway and lands onscreen, it’s a punchline, not a jump scare: her ludicrously capacious floral-print handbag, her comically overlined lips, and her Chappell Roan wig, just slightly askew. Veteran actress Amy Madigan inhabits Gladys with panache. She isn’t just funny—she’s a joke. She’s your aunt that posts on Facebook too much, who works part time for Mary Kay and can’t identify when an image is AI. What could be less threatening than a kooky old lady?

But her clownishness quickly gives way to jaw-dropping violence. Aware that the principal plans to perform a wellness check on Alex at the house where Gladys has imprisoned the missing children, the witch makes a pre-emptive house visit of her own, interrupting Principal Marcus’s lazy hot-dogs-and-TV Sunday with a stunning show of brutality. Gladys’s mind-control powers closely adhere to many of our most foundational tropes about the occult. She subjugates her victims with nothing more than a bowl of water, a mysterious gnarled stick, an object from the person she wants to target, and a hair from the one she wants to control. In other words: a cauldron, a magic wand, and two talismans. That’s basically Hermione’s year-one shopping list for Diagon Alley.

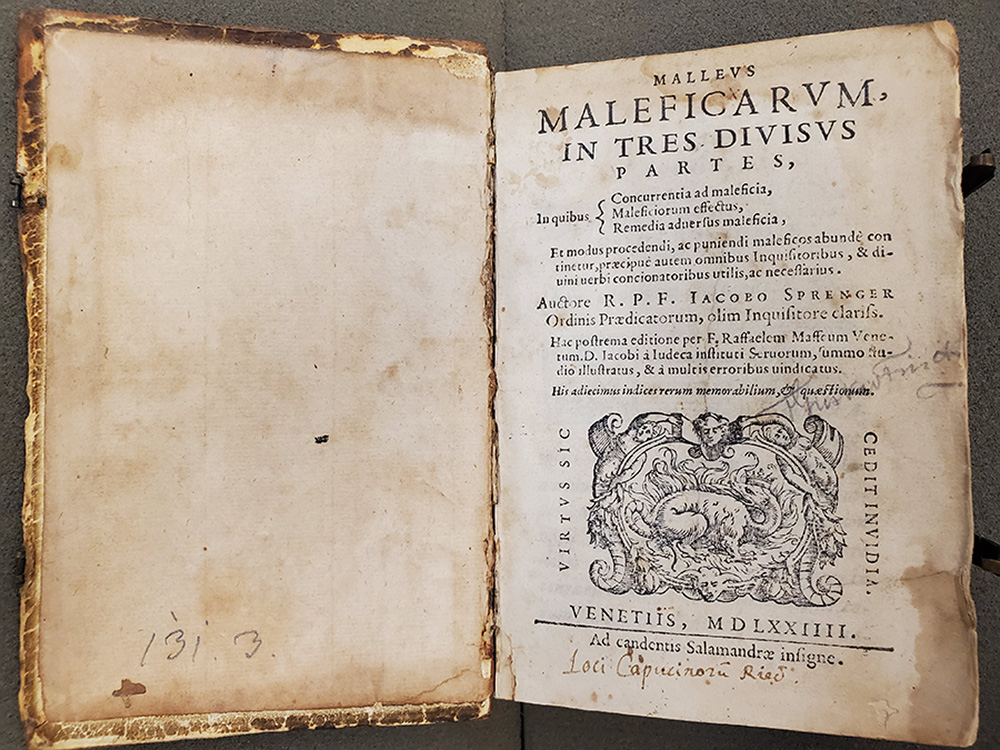

But Gladys is decidedly not a Hogwarts student. No, she doesn’t belong to the Wizarding World, but rather to another problematic but extremely popular text, one that pre-dates Rowling’s by about five hundred years. The Malleus Maleficarum, or, the Hammer of the Witch.

The Malleus Maleficarium was first published in 1486, penned by German theologians Johann Sprenger and Henreich Kraemer as an utterly serious bid to arm the everyday 15th-century Christian with the tools they would need to do battle with the witches in their village. It’s essentially “Witch Hunting for Dummies.” Divided into three sections, the Malleus begins with an argument for why witches are real; then goes into expansive detail about all the kinds of mischief and devilry they’re up to; and then closes out with helpful suggestions on how to identify, arrest, and, ideally, burn these despicable women at the stake.

The Malleus had serendipitous timing; it arrived just thirty years after another German, Johannes Gutenberg, invented the printing press. What might have been a harebrained footnote in Christian theological writing instead benefited from the multiplying magic of Gutenberg’s invention. The Malleus went viral, early-Renaissance style, being reprinted twenty times between 1574 and 1669. It circulated widely until well into the 18th century, whipping up desire for and informing the proceedings of murderous witch hunts for three centuries.

The misogyny of the Malleus is exquisite. It verges on erotic in its swooning, flowery language about the inherent sinfulness of womankind: “What else is a woman but a foe to friendship, an inescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation, a desirable calamity, a domestic danger, a delectable detriment, an evil of nature, painted with fair colors.” (Just once, I’d like one of my exes to refer to me as a “desirable calamity”). It’s giving incel. It’s giving male loneliness epidemic. It’s giving “Hellfire” from The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

The Malleus makes a point to underline that sorcery is only achieved through demonic power. The “charms” that these witches carry—perhaps, in reality, talismans passed down through folk tradition or remnants of pre-Christian paganism—are useless tchotchkes. The witch’s superhuman abilities cannot be derived from her own spirit or study, but must be purchased from a male entity. In his book Devil’s Contract, writer Ed Simon makes the point that in Christian imagination, the witch is making a bargain with the Devil: “the coven is called such for they are covenant with Satan; the witches’ Sabbath may be a demonic ritual, but it’s also an act of exchange, of betrothal, of contractual obligation.” He specifies, “An initiate into witchcraft enters into such a bargain for gain, as any Faustian figure does.” There is no room in this framework for divine feminine power.

Though we might assume that Sprenger and Kramer were just reiterating a long-held European conception of the witch as business partner/fuck buddy of Satan, Simon argues that the Malleus invented this stereotype: “Kramer and Sprenger’s book was responsible for reformulating the conception of the witch from the vague but tolerated folk healers of the Middle Ages into the manifestation of pure Satanic evil.” By “grossly embellishing magical folk practices,” these hysterical Germans codified the Christian nightmare of the witch for centuries to come.

Kramer and Sprenger’s witches have an extremely packed schedule of evil-doing. Because of their covenant with Lucifer, they can fly, turn people into animals, sicken livestock, cause crops to fail, and generally sow discord and chaos. Witches are also in the habit of stealing sperm and sometimes even entire penises. (There is a subchapter titled “Question IX. Whether Witches may work some Prestidigatory Illusion so that the Male Organ appears to be entirely removed and separate from the Body?” in which the male writers debate for several very long paragraphs whether witches are actually stealing penises, like literally physically removing them, or just making the penises appear to be absent through a glamour. It’s this pedantic attention to detail that tells me that Kramer and Sprenger would have loved Reddit.)

But the most dastardly part of the witch’s nightly routine is, of course, their penchant for preying upon children. The Malleus is littered with references to child-killing, child-eating, and fetus-aborting. The text returns obsessively, with an eye-twitching mania, to the fear that witches are coming for the kids:

“Certain witches, against the instinct of human nature, and indeed against the nature of all beasts, with the possible exception of wolves, are in the habit of devouring and eating infant children.”

And who are these witches? Women of child-bearing age were certainly capable of devilry, but throughout the text, there is a particular suspicion directed towards more mature women. The Malleus contends that even the gaze of an old woman is enough to curse a child:

“The evil eye, which is sometimes brought about by the glare or gaze of an evil-minded old woman looking at a child, as a result of which the child is changed and receives the evil eye…”

The Malleus specifically warns of “witch-midwives,” crafty sorceresses who use their position as midwife to steal babies for ritual sacrifice:

“For when they do not kill the child, they blasphemously offer it to the devil in this manner. As soon as the child is born, the midwife, if the mother herself is not a witch, carries it out of the room on the pretext of warming it, raises it up, and offers it to the Prince of Devils, that is Lucifer, and to all the devils.”

There is of course a grain of twisted truth in this horrifying image, because for most of human history, a midwife and an abortionist were one and the same. The woman who guided you through a wanted pregnancy was the same one who would help you end an unwanted one. In reality, the wise-woman of the village may have helped a woman induce a stillborn child that would never have lived, saving that woman’s life. But look at her through the prism of Christian paranoia, and you might just see a witch, a child-killer, firelight dancing on her grinning face as she offers another untarnished infant soul to her master.

Biblical references are littered throughout the Malleus as both justification and evidence. The most central Christian tenet is from Exodus: “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.” But don’t fret: the Malleus very helpfully provides a specific how-to guide on the steps you can take to identify, prosecute, and exterminate the witches in your community (spoiler: it’s torture! Torture is the only thing that definitely works!). The implication here is that it is worse to allow a witch to live unscathed than it is to accidentally torture and kill an innocent woman.

It’s hard not to hear the echoes of the Malleus in the contemporary discourse of hardline American Christianity as it relates to abortion. Since Roe v. Wade was reversed on June 24, 2022, hundreds of American women have once again been forced to bleed out in parking lots, at home, at work, because they were refused medical care for a miscarriage. Women and girls have screamed through the birth of a child they did not want, because it is seen as better to ruin a woman’s life than to end a pregnancy. Then and now, women’s suffering is just the cost of doing holy business.

If motherhood is a woman’s greatest calling, in Christian terms, then it follows that witches are the inversion of this. The sacred Madonna, the Mother Mary, was a mortal woman who made a pact with God to birth the Messiah. She was a paradox, virgin and mother at once, and this paradox made her holy. Witches are also a paradox, but an unholy one. Witches have sex, as much as they want, but bear no children. (Perhaps Satan has provided them with some kind of supernatural IUD?) They steal men’s sperm without any intent to plant it within their wombs. They have no use for men, because they do not wish to be wives and mothers. Witches aren’t just women without children, witches are women who do not care about children.

______

It’s 2016. I am hanging out with a boy in his frat house, and we are “watching a movie.” For reasons that I couldn’t possibly recall, we have selected Robert Eggers’s The VVitch, which came out the previous year. The film was, of course, just an empty gesture of pre-hookup formality, but I remember being drawn to the film, sucked into its spell, and vaguely annoyed when the laptop clicked shut thirty minutes in so we could get down to business.

I returned to The VVitch on my own a year or so later and was enchanted. I grew up in Massachusetts, which means that the Salem Witch Trials loomed large in my historical imagination. Apparently they did for Eggers, too, whose historically rigorous directorial debut about a pious family in 1600s New England losing their minds over the threat of a vvitch in the vvoods gave us so many iconic things: Ralph Ineson’s super-rumbly voice, Anya Taylor Joy’s breakout role, and death by goat attack.

Tweenage Thomasin (Taylor-Joy) belongs to a large family—Mother, Father, brother, boy-girl toddler twins, and newborn baby—within a Puritan colony in the New World. But they soon venture out on their own, because Thomasin’s rigidly pious dad (Ineson) is actually Too Hardcore for even the zealots on the Mayflower. Isolated at the edge of a vast forest, the family begins to suffer strange misfortune. When the newborn baby goes missing on Thomasin’s watch, the family unit unravels, and Thomasin becomes the locus of blame.

The Malleus warns us that the Devil will tempt women, and in their weakness, they will trade their souls for a life of hedonism and supernatural power. In Eggers’s film, this scene plays out like clockwork. A belittled, beleaguered, broken Thomasin—having been blamed for the family’s misfortune, watched her father die and been forced to kill her own mother in self-defense—is now utterly alone in the world. She seeks out the goat Black Philip and begs him to speak to her. A silky male voice drifts in from the ether: What do you want? Thomasin steels herself. What canst thou offer? she asks. She’s already been accused of witchcraft. Might as well make it official and get something in return.

Eggers’s film encourages meta-filmic commentary on who the real villains are here. But within the narrative of the story, he provides a straightforward rendition of the witch of Christian anxiety, the very witch foretold in the Malleus. Thomasin signs her name in the Devil’s book, sheds her clothes, and walks naked into the forest to join her newfound coven sisters. As they dance around a bonfire, they begin to levitate. Thomasin laughs, finally, wild, free, gloriously profane. Just like the Malleus warned us, there are women in the woods, they have given their soul to Satan, and they have gained impossible powers. If we are meant to take the earlier events of the film literally, then Thomasin will, herself, one day venture out of the woods to mutilate babies, sicken children, and possess beasts. It’s just what women do.

Not exclusively women, though. According to the Malleus, the witch is a feminized creature, but not strictly a female one. The Malleus takes pains to point out that witchcraft can be conducted by either men or women. The fact that witches are overwhelmingly female is just that women are much weaker than men, much more easily tempted and seduced (Eve, apple, etc).

The witch has become so inextricably tied to the two-sided cultural coin of female oppression/empowerment that we often gloss over the fact that, throughout history, men were also accused of and murdered for witchcraft. Of the nineteen innocent people who died in the Salem Witch Trials, five were men. The rampant misogyny of the time made it so the target of the Salem attacks was heavily tilted towards older, unmarried women who wielded social or economic capital (i.e., women who were not under the control of a male family member). But men were executed as well, often men who refused to carry out the witch hysteria. Men could be Satan lovers, too.

Which brings us to Longlegs (2024), directed by Osgood Perkins.

Much discourse has already been made of the queer overtones of Nicholas Cage’s performance as the titular Longlegs, a reclusive and exceptionally creepy dollmaker. With his lilting voice, penchant for plastic surgery, and hyperfixation on a really specific, expensive, and fussy hobby, it’s clear that there is, at minimum, some intentional gender-bending at play here. Given the FBI investigation that frames the film, comparisons to The Silence of the Lambs’s Buffalo Bill are apt. There’s a very cogent argument to be made that Longlegs is another example of the horror genre exploiting homophobic and transphobic tropes to “other” its villain, equating queerness to mental illness, pedophilia, and monstrosity.

But Perkins did not make a grounded police thriller in the vein of The Silence of the Lambs. He explored nightmare and fantasy, like Cregger, and drew on the same well of Christian anxiety to fuel his villain. The final act of the film, much like that of Weapons, reveals that the detective work ultimately is just human flailing against supernatural power. A captured Longlegs grins as he credits “the man downstairs” for helping him murder the children and families. The dolls he makes are not just creepy; they are very literally possessed by the spirit of the Devil. Longlegs is not himself a killer. Like Gladys, he uses black magic to make other people do the dirty work. Because he is a man, we want to place him within the canon of male evil, which is the serial killer. But he doesn’t belong to the serial killer archetype, because he’s a witch.

Yes, a boy witch! And Longlegs is the model male witch in that he, like Gladys, like all witches, is predatory towards children. A happy agent of the Devil, he uses his weird doll habit to undermine seemingly happy, “normal” families, infecting the fathers with madness and causing them to kill their daughters and wives and then themselves. Gladys, VVitch, Longlegs – distinct in their manifestations, these arthouse horror villains all ultimately follow the same blueprint that the Malleus laid out five hundred years ago. A covenant with the Devil; spellcasting; and children as their target. Magic-wielding, Devil-backed threats to the family unit.

Danny and Michael Phillipou’s Bring Her Back (2025) features a more naturalistic take on the child-abusing witch, in the form of a foster mother gone horrifically wrong. Intent on bringing back her drowned biological daughter, a longtime social worker, Laura (an absolutely chilling Sally Hawkins; you will never feel the same watching Paddington again), plans a demonic personality transplant. She intends to put the soul of her dead daughter into the body of an unsuspecting new foster child, the vision-impaired Piper. The only wrinkle in her foolproof plan is that Piper has a protective and loving older step-brother, Andy; a fifteen year old, grown enough to threaten Laura’s plan.

Thematically, the film is a scathing critique of the foster care system and the children it fails, but Hawkins’s Laura still feels right at home along Gladys, Longlegs, and VVitch. There are flickers of Hansel and Gretel at play here—a brother and sister trapped in a witch's house, cannibalism—and a single woman, without biological children of her own, making a pact with the devil in order to abuse and ultimately murder defenseless children. Laura is motivated by the grief of losing her own beloved child, yes, but she has a disturbing disinterest in the welfare of the children that have, legally, been placed in her care.

Once again, we are reminded that the worst thing a woman can be is a woman who does not care for or protect children. The ultimate perversion of womanhood is a lack of maternal instinct. The witch is the older single woman with the nice house. The witch is the man with the too-long hair and the female roommate he isn’t fucking. The witch is childless and a little too into their hobbies.

I suspect the residents of the town in Weapons would have been very receptive to the Malleus if it had been posted on their NextDoor forum.

______

Peek through the catalogue of “elevated horror” from the past ten years (championed by indie studios like A24 and Neon, and epitomized in filmmakers like Eggers, Perkins, and Ari Aster), and you’ll find a veritable bumper crop of Malleus-grown witches grinning back at you. In 2018 there was the coven of Ari Aster’s Hereditary and the dancing she-devils of Luca Guadignino’s Suspiria remake. Before Perkins made Longlegs, he gave us a stylish take on the child-eater in Gretel and Hansel (2020). Given the cultural facelift that witches had received in the early 2000s—the proliferation of witch as good-hearted protagonist, the Elphabas and the Hermiones and the Sabrinas—why is the witch of the Malleus suddenly reappearing now, so profusely?

In Caliban and the Witch, author Silvia Federici points out that while we think of witch-hunting as belonging to ancient history, to the Dark Ages, the historical record disputes this. Witchcraft mania was not “the last spark of a dying feudal world.” Rather, the spike in active persecution of witches arrived much later, peaking in the 15th-17th centuries. She argues that hysteria around witchcraft was a crucial phase of the development of capitalism and the formation of modern class dynamics, because it “deepened the divisions between women and men, teaching men to fear the power of women, and destroyed a universe of practices, beliefs, and social subjects whose existence was incompatible with the capitalist work discipline, thus redefining the main elements of social reproduction.” Stoking fear of witches sowed gender discord at a time when the peasant class might have banded together to take down the landed gentry. It was not just misogyny at work, but also a kind of spiritual union-busting, “an essential aspect of primitive accumulation and the ‘transition’ to capitalism.”

The cutting-edge horror filmmakers I’ve discussed may or may not have had the Malleus on their mind when they were crafting their villains. Whether by intent or accident, they have nonetheless hit upon a rich vein of fear within our fundamentally Christian, puritanical American culture. Always beneath the surface of white, Western culture, she lurks: the hag, the Satan-lover, the child killer, the un-mother. I don’t think it’s any wonder that she makes for a potent and buzzy box office monster in 2025. Birth rates are plummeting, women are outperforming men in education and the workplace, everyone’s gay and in a polycule—according to the capitalist Christian conservative, there is an outright war on the traditional values, on masculinity, on “normalcy.” The safety of children and the sanctity of the nuclear family have always been powerful weapons for the ruling class, on a personal and political scale. Nevermind the cost of groceries, nevermind that your health insurance won’t pay for that surgery. Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live!

And yet, she lives. Repulsive Gladys has become a camp sensation—the heroine of memes and thinkpieces and cheeky Letterboxd raves. She’s a fashion icon. An Aunt Gladys prequel film has been greenlit.

We are forever redefining the witch—forever growing scared of her, pointing fingers, throwing her in the water to see if she sinks or floats. Until we have killed her—drawn and quartered her, in Gladys’s case—and then we start to wonder. What was her side of the story?

As I wrote this essay, I remembered another childhood touchstone of witchcraft. One that I think I must have buried in my psyche, because I found it so frightening: Roahl Dahl’s The Witches (1990). On a vacation at a strange seaside hotel, a pair of nosy children uncover a literal conference for witches (as a child, the UCB-grade comedy setup of this premise was lost on me, because I did not know what a conference was). The most iconic scene is the moment that the witches, believing themselves to be alone, strip off their human disguises and allow their true, and truly hideous, witchy bodies loose.

A snatched Angelica Houston pulls off a flesh-mask to reveal a gigantic, beak-like nose; removes her wig to show a scabby, bald scalp; kicks off her kitten heels as horrible talon-like feet emerge. The witches shriek in glee as they shed their attractive facades. They revel in their ugliness, finally free, finally not having to hide, perform, pretend. Watching this scene as a child, I felt fear and disgust.

Rewatching this scene now, as an adult woman, I feel something entirely different. Relief.

Every woman on planet earth knows the ecstasy of finally taking off an uncomfortable bra at the end of a long day. The pure joy of removing the painful high heels, of wiping away the stage makeup of life, allowing your true face, with zits and eye bags and wrinkles, to emerge. After spending the whole day pinched and primed and presentable, performing womanhood for the benefit of everyone else, there is an absolute shrieking joy in its release.

This fall, I happily trotted to the theater to watch Wicked: For Good with my entire family. My millennial theater-kid heart swelled three sizes as I listened to Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande harmonize flawlessly on “For Good,” their long, false lashes wet with tears, their primed and highlighted faces glowing under flattering lighting setups. Wicked’s bittersweet ending does not promise that tomorrow will be perfect, but if we speak truth to power and embrace our unique gifts, we can change the world for the better.

As I stepped out of the theater into the cold Massachusetts night, I found myself wondering whether I still saw myself in these lip-glossy, activist witches the way I did when I was thirteen. I’m thirty-one now, living in a country that has twice elected Donald Trump, where Roe has been reversed and significant swathes of the male population feel comfortable publicly embracing misogyny.

What kind of witch am I? A Good Witch? Or a Bad Witch?

Aunt Gladys is everything that society tells me I should fear becoming: single, childless, ugly, lonely, old, sick. And yet she snaps her evil little sticks with such glee, such freedom. She is repellent and delicious. There’s an unbridled power in those horrible double-iris eyes, something I recognize. It’s like she knows me. It’s like she’s known me my entire life.